This biography is based on an interview with Karen Palmer nee France in 2017 for the Early Medical Women of New Zealand Project

Contents [hide]

Childhood: a scientist in training

Karen France was born in Karori in 1938, the oldest of Thelma and Dall France’s three daughters. The family moved to Plimmerton in 1940, and Karen began her primary school education at Plimmerton School in 1943. A year later, the family moved to Wellington, where Karen’s new primary school wanted to hold her back a year, thinking that her short stature meant that she wouldn’t be able to cope with others her age. Instead, Karen went on to excel in her studies and became dux of her standard six class. She was particularly inspired by one of her teachers, Mr John Sutton, who encouraged her love of problem solving and reading, and Karen fantasised that she would one day save the world like the book character Dr Schweitzer.

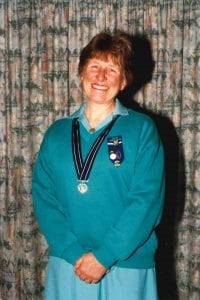

‘Out of Hours’: Presented Kauri Award for Service to Girl Guides New Zealand

Karen applied her scientific and enquiring mind to everything that she did. As a young girl, she was fascinated marine life, and her family once went searching for her when she spent the afternoon exploring local rock pools and failed to return home from school. Tramping was in her blood, and as a child Karen and her friends would roam freely around the neighbourhood and Mount Victoria, until there was a murder in the local area that put a damper on their freedoms. When she later became the leader of the local Girl Guides group, she would take the other girls on hikes so that they could investigate the natural wonders around Wellington.

Karen’s secondary school, Wellington East, was decidedly less inspiring. Alone with her interest in science, Karen was forced to study these subjects by correspondence as there was no science teacher available, unlike the coveted Wellington Girls’ College that was more welcoming to academically-minded girls. When Karen mentioned that she’d quite like to be a doctor, she was told by the careers advisor that she wasn’t bright enough, and that teaching might be a better option. Karen spent her school years learning what she saw as “useless” things, such as home science, and maths—failing to see the point of geometry. However, she did particularly enjoy ballroom dancing, despite the failing talents of the local boys. Karen pleaded to go straight to university from sixth form, which her parents denied because of her youth, and instead she spent her last, renegade, year sitting outside the classroom door as punishment for making some comment or other.

Despite these tribulations, the highlight of Karen’s final school year was her elected role as school librarian, where she could express her love of books.

“I loved books, you can see I’ve got books all over. But we grew up with library books, and if we owned a book it was like owning gold. And so, when I buy a book or give a book to the children, or the grandchildren, I expect them to look after it.”

University studies: training in science and medicine

Karen and other BSc students sleeping on the street while waiting for All Blacks tickets

Karen went to Victoria University in 1955 to study a Bachelor of Science. Her mother decided to work part-time to cover her university costs, against the wishes of her father who felt it was his role to provide for the family. Karen herself worked a variety of jobs during university, including as a cook where she could prepare sixty perfectly cooked poached eggs, and sorting mail in the general post office where she was chastised for working too efficiently.

Karen’s undergraduate science studies included geology, chemistry, the dreaded maths, zoology, and physics. As before, Karen was known for asking questions, and her botany teacher in particular found her inquisitive nature difficult to deal with.

“I kept asking her questions, and she couldn’t always answer them, and she used to get a bit irritable about it. And when I think about it now, of course, she would.”

Karen was only one of a handful of girls studying science. After their final zoology exams, Karen recalls going to St George’s hotel to celebrate, where she sipped a non-alcohol ginger beer in the women’s lounge while her male peers celebrated in the bar.

Back row (left to right): Gail McLean, Ruth Schell (nee Stevenson), Karen Palmer (nee France)

Front row (left to right): Harvey Morgan, Jack Wong, John de Geus

After graduating with her BSc, Karen’s mother—a rebellious woman who had worked as a nurse herself—persuaded Karen to enrol in medical school. Although Karen had considered pursuing a career as a research scientist, she found she thoroughly enjoyed her time in medical school. Once again, she struggled with those subjects that seemed pointless to her, such as learning the intricacies of anatomy.

However, the biggest struggle in medical school was dealing with sexist comments from teachers, which could be viewed as harassment by today’s standards, and Karen recalls that one female student dropped out after the very first day. One orthopaedic surgeon was so famous for his derogatory comments that sometimes the male students would come and support the girls when he was nearby.

“Now we were pestered and positively assaulted, in my inverted commas, by some of the tutors.”

The dress code in medical school was formal, and although one brave male student was popular for ignoring the rules, Karen found it more difficult to challenge expectations. She recalls being terribly ashamed after she was caught dressed in casual slacks, even though it was outside of the normal university hours.

“I thought, it was pretty safe in the school holidays, in the university holidays, I can go up into the anatomy department and look at my results. And as I got up the steps into the anatomy department, I was confronted by the professor, Professor Adams, who said, looked me up and down as if I were some sort of street person…”

Karen is pictured with her beloved (10 pound bicycle). She could not reach the pedals from the seat!

After her final sixth year spent studying and working in Wellington, Karen graduated in 1964. Of the 20 girls who started medical school with her, just 14 went on to graduate. Karen’s family attended the event, where she remembers her father was very nervous about the social demographics, thinking that everyone else there would be very stereotypically wealthy. With the hard work now behind her, Karen admitted some relief to have finished her studies.

“When we graduated from medical school, I amongst most of my other friends said, thank god that’s all over, we would never do it again if we knew how bad it was going to be.”

Entering the workforce: training and studying in the UK

Karen’s first job as a house officer was split fifty-fifty between anaesthetics and tuberculosis wards in Wellington Hospital, where she experienced a period of anxiety about her inconclusive screening results from the Mantoux tuberculosis test. The junior doctors worked very long hours and Karen remembers feeling so tired that she could barely walk around the wards. She lived in the hospital with other house surgeons and registrars, in a separate women’s area, although the girls were allowed to go into the men’s billiard room.

“They were keen that you didn’t touch the billiard table, in case you spoilt the felt. They obviously thought we weren’t equal.”

Karen’s next job was working in casualty in the Hutt valley, where the most memorable event was being punched in the face by a man who had taken an overdose. The sister working with her called the larger male house surgeons to come and help them restrain the man.

“Now some of them are quite large lads. Now if this had got to the papers, we would have all been up for assault, today. “How dare you sit on a patient”. Well, I can tell you, you have to. And we thrust the tube down his gullet, and blood nose and all, and washed him out. And he didn’t say thank you. I don’t remember what happened to him, he may well have gone to a psychiatric unit.”

Karen’s registrar training began in 1967 in the Hutt Hospital. Here she met her fiancé, Don—a dental school graduate—and the two were married two years later. After a 9-month stint as a pathology registrar in Wellington hospital, Karen decided to go to England for postgraduate studies in paediatrics. Supported by a scholarship, in 1969 Karen and her husband travelled to London, where she completed her Diploma of Child Health at Great Ormand Street. Karen and Don were married in the following March.

Karen’s career diverged into geriatric and rehabilitation medicine by chance. After completing her Diploma, she was offered a job at the Elizabeth Garrett Anderson Hospital in London, which she turned down as Don did not have a job. However, when he found work a week later, Karen was left jobless, and decided to accept a new offer as a Senior Medical Officer at St Pancras Hospital specialising in geriatric medicine.

“It was marvellous, I had a ball. Huge teaching unit, well huge in the value, there was only about fifty or sixty patients. But huge value teaching value with Professor Exton-Smith from University College Hospital in London. He published papers, we talked, we had clinics, we had everything that I really enjoyed enormously.”

Building a family

At this point, Karen discovered that she and Don were expecting their first child. Although they lived in London’s East End, Karen would sleep at St Pancras Hospital when she was on call. When her well-built husband stayed the night with her, the single bed she was provided with would collapse. However, despite her pregnancy, Karen was told that the couple would not be provided with a double bed as the hospital could not accommodate for married junior doctors.

Representing the London and South East of England ‘Cook of the Realm’ while working as a senior medical officer at Athlone House Geriatric Unit, Middlesex Hospital.

After six months at St Pancras, Karen transferred to the Middlesex Hospital Geriatric Unit at Athlone House, Highgate—a new unit of sixty beds—to work as the Medical Officer. When Karen gave birth to her first child, her boss was supportive, arranging for her to have six weeks maternity leave, after which she returned to work with her baby in a carrycot. She found her workplace a friendly, family environment, and was immensely grateful to the secretary who cared for her young daughter while Karen saw her patients.

However, it wasn’t all hard work. While living in the UK, Karen played a starring role in a British cooking show. Her famous moment was when she cooked a pavlova for dessert using dried fruit on it instead of the fresh ingredients she was used to.

“Derek Nimmo was one of the judges, yes judge, and he came over and ate about two-thirds of it. “I’ve just come back from New Zealand,” he said. Oh god, it was unbelievable. Well I didn’t win the competition, but I came home with a three-oven stove, lots of wine, cooking implements for the kitchen.”

Karen’s second child, a son, was born on Christmas eve 1973, and the family moved back to New Zealand three months later, via a stopover in Los Angeles. Here they experienced some of the entertaining challenges of travelling with young children, including being forced to share a bed with her baby when the American hotel staff didn’t understand what a ‘cot’ was, and her daughter running up and down the plane aisle yelling “Fire, Fire”.

After arriving home, Karen and her husband bought a new house in Ngaio north of Wellington, and settled back into their Kiwi lives, and in 1976 they had their third child. Karen recalls returning home from hospital with her newborn baby boy to a stinking house after a stormwater drain flooded their house and destroyed everything in their garden and downstairs living area.

Financially, times were tough and as both Karen and her husband worked fulltime, childcare was an ongoing issue. At first, they employed their previous nanny from the UK to look after the children and prepare the evening meals. When that didn’t work out as they had planned, Karen used the local crèche or employed friendly neighbours to look after her children when school finished. Only once did her husband need to buy her flowers to apologise for forgetting to collect the children.

Karen’s husband later died in 1991. Although Karen found Ngaio a wonderful community to live in, after years of working long hours, Karen found it difficult to expand her social networks.”

“If you work full time round the clock, you don’t know your neighbours. I mean you know them by name, you say hello, and that’s all you know. And they don’t know you… But I would go on parents’ evenings to help, and I’d be the one washing the dishes while everybody else did the discourse behind me. And I didn’t know what they were talking about. I didn’t know who they were talking about or what they were talking about, because I didn’t know anybody.”

The art of problem-solving: a career in consultancy

Karen’s skills in problem solving that she had nurtured back in primary school eventually grew into a full-time career.

“The thing about medicine is it’s all problem-solving… When I look back on it, my only route to what I ultimately did was that I had to be a consultant. Because what I was picking up was what people couldn’t solve themselves.”

Before returning from the UK in 1974, Karen was in hospital receiving a postpartum blood transfusion when she was visited by a man she had never met before, where she found out that she was not the only specialist employed in her new role as medical officer at the Ewart geriatric and rehabilitation unit.

Chair of the New Zealand Committee of the Royal Australasian College of Physicians, and New Zealand Councillor of the Royal Australasian College of Physicians

“I didn’t know who he was from a bar of soap. And he said, “Oh, I’m taking over at Ewart.” And I thought that was my job, you see, because we’d already made enquiries… And I must admit, sitting with a blood transfusion going on, with somebody coming to tell you that he’s doing the job you thought you had was not great.”

However, Karen and her new consultant colleague shared their job amicably, under their own enterprises, working together to get the new unit up and running. Karen enjoyed her working relationships with the other staff, until 1989 when the Ewart unit shut down due to poor funding and patients were re-distributed to either side of Wellington Hospital.

“I’m still in touch with some of the original staff. And we have Ewart lunches every three months, we go to the Chocolate Fish, we don’t eat chocolate, but we talk for two hours and then we drive home again… I loved it. I think the thing was, I had a team of nursing staff who were as focused as I was. Physio staff. I’m friends with some of the original physios. It was because we were a small unit, 100 people working there, I was friends with the kitchen staff, I was friends with all the OTs, physios, social workers, and the nurses. And when we meet up, we still, it’s still exciting.”

The hospital’s failing finances meant that Karen’s colleagues gradually disappeared from around her. For the next 11 years, Karen found herself working as the only consultant, albeit supported by a very good senior registrar, where she needed to arrange cover from other physicians so that she could have time off occasionally.

“So because the money talks much harder and louder than anything else, people don’t count. We might as well be what all the governments tell us over the years, we might as well be baked beans, quite frankly. Because we’re only worth that much. We’re expensive beans, I’m gold plated, but that’s all we are. We’re numbers.”

Representing the New Zealand Geriatric Society (as President) at the Australian Geriatric Society meeting in Darwin, Australia

Karen was the Head of Department for Geriatric Assessment and Rehabilitation Services for nearly ten years. Towards, the end of her career, Karen’s role moved largely into administration and management, where she did her best to make a positive difference. Around 2005, she spent six months working as the Acting CEO for the Wellington Hospital Board, where she was forced to make unpopular budget cuts. She found this a difficult time, and she lost many friends. Even after giving up the role, Karen clashed with the new management staff. Karen left for a month-long holiday overseas, taking cooking classes in Italy, travelling through Hungary and Poland on a bus, and attending a wedding on the Isle of Wight. When she returned home she found she no longer had a job.

Despite the bittersweet ending, Karen can look back at all she achieved as a consultant in rehabilitation medicine. Throughout her career, she co-authored ten research articles on postural hypotension, and was a clinical lecturer for twenty-five years at the Otago Medical School, with many registrars and consultants training under her.

“During my time I’ve done a lot of things in the hospital as well, I’ve been chairman of the senior medical staff. I’ve been involved in all the rehab, the Ministry of Health had me on their nursing council. You know you do a huge amount of stuff while you’re there. And it all goes along with your clinical work. It’s all about, there’s a problem here and we need to get it sorted.”

Getting back to nature: retiring into research

While Karen’s career in consultancy came to a close, her new life in academia was just beginning. Over several years Karen worked her way extramurally towards a Graduate Diploma in Science from Massey University, with a focus on environmental studies, allowing her to return to her childhood love of nature and the outdoors.

“I absolutely had a ball, I would go up there in the weekends, I would collect my specimens, I did my plot discussion, I would identify plants I hadn’t seen before, I just had a ball. And they gave me an A+ which I thought was quite good.”

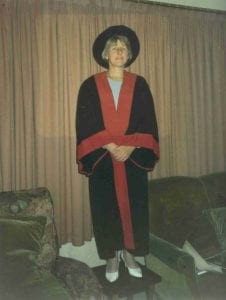

Graduating from Massey University with a Graduate Diploma in Environmental Studies with Distinction

Despite her role as a senior lecturer, and the BSc she had already earned, Karen started again from the very beginning with entry level papers. She would take time off from work to go on field trips, with a class half-full of older students, who would sit at the front of the bus asking questions while the nineteen-year-olds sat in the back singing songs and passing the time.

“We all get together at wherever we were staying for the night, we’d go up Mount Egmont and be staying in some forest hut or something. And it was an absolute ball. We went to Auckland, I can’t remember where we stayed now, it must have been a backpackers or something. But we would look at sewages and things that that you don’t necessarily go and do.”

Karen was an excellent student, and although her old nemesis—mathematics and statistics—came back to haunt her, she graduated from her Diploma with a distinction. She then went on to complete a Masters of Applied Science in Environmental Ecology, researching the ecology of a stream in Paekakariki north of Wellington that had been a picnic area 30-40 years ago. Karen’s ‘long-suffering’ children would go with her on the field trips and bash posts into the ground for her, while she battled the elements.

“The field was full of Herefords… Well of course, they’re not going to hurt you, but they will hurt you by default because they push and shove. But they’re not going to be bothered otherwise… So I managed to crawl along the fence and go back out through the gate, where a large bull was sitting. Fortunately, the bull is a placid sort, and I managed to get back to my car, so there was not much fieldwork done that day. I went and had a long coffee.”

Finally, Karen decided to launch into a PhD, admittedly motivated by her own daughter’s experiences with her doctorate, and is proud that her research is freely available in the Massey University Library for anyone who may find it useful.

““Why are you doing this?” said the guy, the head of department. And I said, “I want to prove I can do it.” I didn’t say to him, I’ve got to prove I can do it because my daughters got one… He said, “What are you going to do with it?” And I said, “Oh, I don’t know. I hadn’t planned anything”, I said, “But if people want to use my information, they’ll be available.” So it is available.””