This biography is based on an interview with Ella’s daughter, Kathryn McKendry, in 2020 for the Early Medical Women of New Zealand Project. The interviewer was Lucy Goodman.

Contents [hide]

Early years: life on a rural farm & a convent

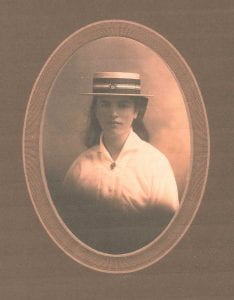

Ella Langley was born on March 24th, 1902 in Dromore, just north of Ashburton. She was the second youngest child in a large but well-off family of the nine children, as well as a girl whose parents had come on hard times. Ella’s father, a farmer, was dedicated to his children, and he taught them all how to shoot. Ella was not a particularly outdoorsy type of person, and with her shaky hand did not excel at these outdoor pursuits.

In 1908, when Ella was very young, her parents decided to go to England, and in preparation, they sent Ella and her sisters to board at Ashburton Convent. Her mother unfortunately died a year later, and Ella remained at the convent for her entire schooling, although she would return home on the weekends.

“They weren’t allowed to have mirrors in case they looked at them too much and thought they were too beautiful, I guess. And she told me that when they were getting out of the bath, they had to have someone to hold up the bath sheets so they could dry in modesty. The naked body wasn’t a thing to be seen. So, I gather… I don’t know how she got on at medical school.”

As the youngest daughter, Ella grew up with less family responsibilities than her two older sisters, which perhaps gave her some freedom to explore her academic potential. In 1915, at the age of 13, she wrote a story that won a competition in The Weekend Press. She was a high achiever, who enjoyed writing and playing the piano, and was awarded Dux of her small school.

“A pupil of the Ashburton Convent, Miss Ella Langley, daughter of Mr T Langley, aged 16 years, has shown marked ability in her studies during the last year. Her successful passes were the Civil Service and Matriculation examinations, higher local examination of Trinity College, and the advanced grade in the Royal College of Music.” [source: The Ashburton Guardian, 1919]

Medical school

Ella’s decision to enter medical school was unusual for the times, although she was undoubtedly supported by her school and her family. However, with limited science education behind her, Ella struggled during her first few years of her studies, achieving only third class in physics and chemistry on her first attempt.

“I’ve no idea what made her go to medical school. But I think the Sisters of the Mission encouraged girls to take on higher studies at that time if they thought they were capable… When she went to medical school, physics was a compulsory subject. And she’d never heard of the word.”

Ella and her friends—including Mary Douglas who graduated the same year—enjoyed the annual capping ceremony, when the male students in particular would take over the town with their celebrations. A highlight of any medical student’s studies at the time was an invitation to meet Sir Lindo Ferguson—the Dean of the Medical School. Ella often recounted this story, where she recalled dressing formally, in gloves and the like, and visiting Sir Ferguson’s home for afternoon tea.

Ella made her way through medical school supported by her father, until he unfortunately passed away in 1923. This left Ella to graduate alone without either parent to witness her achievements.

“She had a cheque book and every term he went through the cheque book with her, and she had to account for everything she’d spent. And whether it was needed or wanted.”

Ella spent her years of clinical training first at Palmerston North, during her sixth year of medical school training, and then at Christchurch Hospital, where she worked as a House Surgeon. Ella recalled that she was the first woman to live-in at Christchurch Hospital.

“She had to wait quite some time before she eventually got [a job] at Christchurch Hospital. And they weren’t keen to take on women, obviously, and the superintendent told her that she had to do everything the men did and that she wasn’t to be treated any differently.”

Family life: child-rearing, creative conquests, and volunteering in the community

Ella met her future husband, Jeremiah Stephen Connolly, when he moved into the neighboring farm in about 1913, during her teenage years. The two attended the same church, played golf, and socialized together before they married in 1928. The couple lived their farming lifestyle, first in Rakaia before later moving to Ashburton, and had five children in rapid succession. Family life kept Ella busy, and she chose not to continue her medical career after raising her children. Instead, she supported her husband wholeheartedly, and as he suffered some misfortunes, and she was mindful not to undermine him by earning more than he did.

Despite the expectation that she would not work, Ella contributed to the medical community in a voluntary capacity. During the war years, she gave lectures to V.A.D.’s, and helped test the quality of the water supplies at the small rural army camps around the region. Over the years, Ella became more regularly involved as a committee member of the Plunket Society.

“She was always in demand, you know, with the Plunket Society and with the crèche duties and things like that. They were always asking her to join them.”

Ella kept up to date with the medical profession over the years, regularly attending seminars given by specialists from Christchurch hospital, and was respected for her medical knowledge in the household and the community. In one instance, a neighbor called her for advice about her husband’s injured arm. Ella saw that it was broken and sensibly advised the neighbor simply to put it in a sling and wait until morning as there was nothing that the hospital would do overnight—practical advice that was not particularly well received by her neighbor.

Ella was sensible with her attitudes towards medicine. While other women often gave their children olive oil as a laxative, Ella was never enthused by ‘home remedies’ such as these, although she did often give her children glycerin and boracic powder in a little egg cup to treat their ulcerated gums.

“We were never dosed with medications, put it that way.”

Always a dedicated writer, Ella wrote faithfully to all her five children when they went off to boarding school, although her children had difficulty reading her writing at first. She was blessed with creative talents that she often put to good use around the home. During a time when materials were scarce, she would make little boys pants out of flour bag lining, and other similarly frugal conquests.

“She did embroidery on our dresses and patterned collars and things like that. And we loved them. There was one thing that I remember about it, one year everyone was in navy blue, red and white. Whether it was something to do with the coronation or not, I don’t know. But my sister and I begged for me to be navy blue, red and white. But no way would she get us navy blue, red and white. We went into dusky pink and brown.”

Later in life: returning to work

In the 1960s, the Ashburton Hospital was struggling with low staff numbers, and Ella decided to return to work there as a House Surgeon. Now aged in her sixties, and without years of medical experience behind her, she was willing to learn from those many decades younger than herself. She thoroughly enjoyed the experience, where she found she particularly enjoyed the problem solving that came with medical diagnosis.

“I know she contacted the superintendent to see if she could be of any assistance. I think he grabbed her with open arms… And I remember, she told me that a board member said to her, “Now don’t let these students tell you what to do”. And she said, “I said to her, ‘Well, they have the most up-to-date training of anyone in this hospital’, she said, ‘I’m happy to be guided—to be helped by them'”.”

Around this time, Ella’s husband was diagnosed with cancer. While still working, Ella spent much of her time caring for him at home, treating him with the latest medications, before he eventually went into hospital.

Following her death in Ashburton Hospital on 23 June 1976, Ella was farewelled at a Requiem Mass in Ashburton and was buried alongside her husband in the Rakaia Cemetery.

Ella’s achievements were an inspiration to her family, and her grandson followed in her footsteps, training as a doctor himself.

“We were all very proud of her qualifications, as a family. And it gave us, as children, a lot of confidence to do what we wanted to do.”