This biography is based on an interview with Helen Bichan nee Simpson in 2016 for the Early Medical Women of New Zealand project. The interviewer was Claire Gooder.

Contents [hide]

Early life: a Minister’s daughter

Helen Simpson was born in Christchurch in 1935, before moving to Dunedin with her family when she was 18 months old. Her father was then the Minister at Hanover Street Baptist Church in Dunedin. Helen’s mother graduated from Victoria University with a BA in French and English and an MSc in Botany. Her parents had met as students through the Student Christian Movement.

Helen was the eldest of six children in her family and has strong memories of growing up with the influence of World War II.

“I was old enough to remember and to read about or hear about the atrocities that were happening in the Second World War at the death camps. My father was involved with refugee re-settlement in Dunedin before the war. The threat of Japan entering the war was real. My parents and my mother’s great friend (from High school) who was married to a farmer in Southland; the two families had some plan for getting the women and children into a back-country farm if we were invaded.”

During her primary school years, Helen attended Arthur Street School in Dunedin. Education was very important in her family, and Helen grew up with the belief that ‘girls can do anything, but with limits’. As the daughter of a Minister, Helen had an awareness of people and their needs. Missionaries on furlough used to stay in the manse so added an international dimension. As a young child, Helen also met many medical students who attended Hanover Street Baptist Church. One of these was her Sunday School teacher, Ada Gilling.

“I knew women could do medicine. I decided that I wanted to medicine right back then.”

When Helen was 11 years old, her family moved to Hawera for her father’s work, where they lived for three years. Their new home—a Manse provided by the church—was backed by an old orchard. Helen and her siblings enjoyed the outdoors, and her mother’s background in science was evident in her encouragement of their learning about plants, birds and ‘creepy crawlies’. The children cycled to their local schools. The polio epidemic influenced children’s lives at the time, and Helen’s first year of high school at Hawera Technical High School started with a month of lessons by correspondence as children were not allowed to gather outside their homes.

Preparing for medical school: self-directed study & finding the financial means

The following year the family moved to Napier where Helen attended Napier Girls’ High School.

Compared to her previous co-ed school, Helen found the science education was limited to biology. Her headmistress recognised the deficit and gave Helen and another student some extra tuition in chemistry outside school hours. However, a good systems overview was provided by a chemistry textbook borrowed from the school library after the end of her last school year. Also of value to university study was self-directed study with four other girls from her upper sixth biology class.

“We’d be in the storeroom working on our own biology stuff, which was terribly useful for university—good preparation. Then from reading the book I got the hang of how molecules and atoms work, and a lot of that stuff. I found when I went along to a class for chemistry for beginners at university, I didn’t actually need it; this book had basically given me a framework. I’m a systems thinker. And, thanks to a good level of mathematics from school I managed to pass Physics 1. ”

Despite the deficit in science education at high school, Helen later found that her English skills were an advantage at medical school:

“ . . they used to complain that many of the boys couldn’t write decent English. My background in English and all the rest meant that was fine. Actually, the same applied to most of the girls in my class; we could all write reasonably well.”

The financial challenge presented the largest obstacle for Helen’s dream of becoming a doctor, as her parents could not afford to fund her through medical school. Along with her classmates she sat the Bursary examination and obtained a bursary along with a boarding allowance. In addition, she scoured the university prospectuses for scholarships, and was awarded a local Hawke’s Bay scholarship. Holiday jobs included nurse aiding at Napier hospital, berry picking, and relief teaching of general science at the end of her first year at university. Helen chose to do the medical intermediate year at Victoria University in Wellington, due to its proximity to her home in Napier and its relative affordability. Here Helen shared a room in the Baptist Youth Hostel with a girl from her high school class, where they dutifully focused on their studies in their cosy living environment.

“Our beds were end-to-end with the wardrobe between us, and there was enough width beside the bed nearer the window, which was mine, for a table. So, we could take turns at swotting on the table, and the other one swotted on her bed. [Our room was] straight across from the Evening Post building, and my friend discovered that the guys on the other side could see into our rooms. So, we were very careful dressing, after that.”

“I was heavily focused on study, because I hadn’t done physics before, at all, and my chemistry was based on the book I’d read in the holidays, basically. So I had my nose to the grindstone.”

Medical school: changing times for female students, frugal living arrangements

Helen did not have alternative plans outside of a medical career, but she was fortunate to be accepted into medical school on her first attempt. In 1954, Helen moved back to Dunedin to begin medical school at Otago University, where she was welcomed by the people at the church who remembered her family from her childhood years.

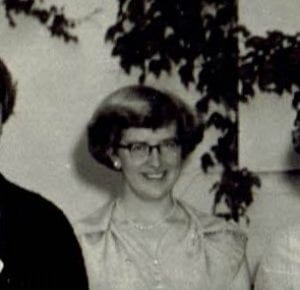

Left to right: Patricia Buckfield, Helen Bichan (nee Simpson), Patricia Wood (nee Houghton), Anne Gillies, Pamela Jones (nee Brown), Helen Angus, Jean Bryant (nee Fyfe)

Helen spent the first two years living at St Margaret’s College where she roomed with a fellow medical student, Pamela Brown, who she had met at Victoria University.

Helen was one of ten women accepted into her medical school class, including two who were repeating a year, and another who dropped out after the first week. Four of these women went on to graduate together, with the others completing their studies over a longer period. Helen’s first memories of medical school was her introduction to anatomy in the dissection room.

“I suppose the thing that hit you when you first go into the dissection room was the smell, and that smell remained with you and with your lab coat.”

Helen’s year was one of the last to accept returned servicemen from World War II. She recalls a certain amount of chauvinism from some of the male students and the teachers, who held preconceived ideas about women’s place in medical school and what they were capable of.

“I remember one of them saying very condescendingly to a couple of us “you’ll be being put through by your parents”, which was blatantly untrue for me. It was that, “you’re just sort of playing at it”, almost, there was a bit of that.”

“One of my earlier memories, the first year in the dissection room, they put all the women on one ‘bod’. The orthopaedic surgeon, who was not very well inclined toward female students, surveyed the group of us walking out and he said, “hmph, you’ll all become school medical officers”. When I think back that entire group landed up as other specialists of some other sort.”

However, times were changing for women in medical school during the 1950s. At the start women were expected to sit at the front of the class in lectures and laboratories—but this custom diminished over the time Helen’s class were going through. She recalls a breakthrough moment in women’s status at medical school was when she was invited to the fifth-year dinner by a male friend—traditionally a boozy affair that women were not welcome to attend.

The first year, we were grouped as women for all sorts of group work, but by second year in the dissection room it changed. We dissected the head and neck in third year, while the second years did the body. So, we were mixed groups then. Similarly, for several other things, they started just including us in alphabetical groups, and that was fine. They sort of stopped treating us as a sub-group like that.”

The medical school students had a full programme and the entire day was taken up with lectures and laboratory classes, and the students would return to their hostel for a hot lunch. During their second and third year, Saturday mornings at 8am was osteology, although attendance was often low. Not until the first major examinations at the end of the second year did the students learn how hard they needed to work to continue at medical school.

“You hit them with 40 as a pass mark, and [these are] people who have been getting 80s or whatever, being glad to get 45. I’m sure it was psychologically intended. You were just glad to get through.”

In her fourth and fifth year, Helen moved into Huntly House behind St Margaret’s College, where she rented the smallest available room. In the first year she and two fellow students shared cooking dinners.

Helen sometimes found it difficult to socialise with people outside of medical school, as some were intimidated by a female medical student. It was well known among women med students that it was a conversation-stopper in mixed circles.”

Despite this, Helen’s social circles at university crossed both medical school and her religious faith, including friends from the Student Christian Movement and the Hanover Street Church group. She enjoyed sports and outdoor pursuits with her friends, was a member of a university hockey team, and enjoyed bike riding up the North East Valley or other areas around Otago, when she found the time.

“I think I hardly ever ate in on Sundays, I’d almost always be invited out to dinner by someone at church. There were a number of single women there who would invite a student or two home for lunch— dinner it would be—in the middle of the day.”

Helen spent her university holidays horse-riding at a Southland farm belonging to her mother’s old friend, or returning home to visit her family. She worked during the long summer holidays, building up a varied employment history over her time at university. As well as teaching science and working as a hospital nurse aid, Helen’s jobs including picking berries, making cardboard products in a factory, working in a jeweller’s shop, and on one occasion she combined work with a family holiday.

“One year, my father had the bright idea that we could pick agar seaweed, combined with a holiday. So, we stayed in Tora, because he knew the farmer there. We lived in the shearer’s quarters and picked up agar seaweed, dried it and bagged it, and sent it off to market.”

Helen found nurse aiding was particularly useful preparation for medical school, giving her an advantage over the boys who usually took more lucrative but less relevant summer jobs in the freezing works or the wool store. In her fourth-year holidays, Helen used a holiday job in the casualty department of Dunedin Hospital to gather data for her fifth year research dissertation. She began a project on wound healing, which later evolved into a larger project investigating how casualty departments operated on a nationwide level. She was awarded a distinction in public health at the end of fifth year which was a successful year for Helen, who also topped the class in O&G and paediatrics.

The students’ fourth and fifth years of clinical training included two weeks during fifth year living in at Queen Mary Hospital to gain experience in delivering babies. Clinical tuition took place in other hospitals, such as Wakari, Seacliff and Cherry Farm. The latter were psychiatric hospitals—an experience that Helen did not find particularly inspirational, despite her later specialisation in this area.

“I don’t think it was a particularly good introduction to psychiatry. We did have a visit to what was left of Seacliff, I think in fourth year. In fifth year we went to Cherry Farm and again visited a ward. That trip also included a visit to the back of the estate to admire their new water treatment and sewage treatment station, which was state of the art and relevant to our fifth year programme on public health.

We had lectures from Dr Harold Bourne, a local psychiatrist, and from Dr Blake Palmer, director of mental health services from the Department of Health. Blake Palmer told us to read ‘Owls Do Cry’ by Janet Frame, because of the way it was set out. She’d written it when in hospital [Seacliff I think]. I think he was probably one of the reasons she didn’t have a lobotomy.”

Helen completed an acting house surgeon placement in Stratford Hospital during her fifth-year holidays, before moving to Auckland for her final clinical year of medical school where her family were now living. The students worked together in groups to complete their hospital rotations, which included an O&G run where each student had to deliver a certain number of babies. Helen remained lifelong friends with two of the men from her group.

“We lived in National Women’s for a bit where we ranked after the midwifery students who got the day deliveries, and we got the night deliveries. In the quarters, we each had a separate bedroom with a very loud telephone. So, they woke you and said “there’s a delivery”; you fell out of bed and pulled your white gown on over your pyjamas—well, dressed partially—and dashed off to do the delivery.”

At the end of the year, the students returned to Dunedin for their final exams, followed shortly by their graduation. Only a week later, Helen returned to Wellington where she married her fiancé, Ron Bichan, who she had met in the Student Christian Movement. They had been engaged since her fifth year of studies.

Early training: house surgeon years & working as a GP while raising a family

Helen and Ron remained in Wellington after their wedding so that Ron could complete his Diploma in Social Science. With house surgeon placements in Wellington Hospital already full, Helen was forced to look elsewhere, eventually landing a job in Masterton. During that year they lived across two flats, spending weekends and holidays together. Despite the practical living challenges, Helen found working at a smaller hospital was an excellent learning experience.

“Because there weren’t very many junior medical staff, I got to do things like the odd appendix, or more complicated sewing up stuff, and during the year we had a genuine little typhoid outbreak —three cases, with a classic spread, somebody with a pit loo and someone else taking water downstream. I learned from the senior nurses how you seriously do isolation, which had almost been phased out with antibiotics, so that the younger generations like me, then going through were not au fait with good nursing technique for infections. From that point of view a very good year, because I got experiences that the junior house surgeons in bigger places simply wouldn’t have had.”

Helen fell pregnant during her house surgeon year, and just managed to complete her requirements for registration before finishing the appointment.

Helen spent time at home with the baby until November 1960 when the family moved up to Mangakino for Ron’s work. At the time, the area was a temporary village built to accommodate workers building the nearby Maraetai and Whakamaru hydroelectric dams and power stations. The family lived in the worker’s end of the village in a 520 square foot house. While Ron worked as a special researcher for the Presbyterian church and then later as the parish minister, Helen did part-time general practice first at Atiamuri and then in Mangakino.

“The Ministry of Works set Mangakino up as a total village, so it had a school and a high school, a golf course, bowling club, cinema, shops, maternity hospital and outpatients. It was basically a completely set-up community. It had a pub, and the churches were there. Of course it also had the lake for trout fishing and boating and all those sorts of things.”

“The maternity hospital and the general practice were in a single building. The general practice operated under the ‘special area’ scheme which meant that the Department of Health employed the staff. Normally such schemes had a single doctor where the population was too small to run the usual type of practice. In Mangakino the Unions held out for the scheme to continue for the life of the village. When we arrived, there were three doctors employed. The region, apart from the town, which was most of the population, included rehab farming blocks. Twenty or so miles away, there was the Tihoi timber village where they were still milling native bush. Whakamaru village upstream, and Waipapa village downstream provided housing for the staff of those two power stations. So, it was a fairly circumscribed area. We used to see the Tihoi schoolteacher on a Friday night; he’d drop into the Manse, and one of his jobs would be to pick up the [contraceptive] Pill for the wives of the timber mill people in Tihoi.”

Only a year after moving to Mangakino, construction of Maraetai 2 dam was mothballed and the village population downsized from 6000 to about 1800 people. Helen and Ron remained in the region for the following six years, while they got to know many people in their small community, and expanded their family to include four children, with a fifth on the way.

Specialising in psychiatry: baptism by fire & an interest in rehabilitation

In early 1967, Helen and Ron moved to Cannon’s Creek in Porirua to pursue Ron’s work. Helen gave birth to her fifth child. In 1969, she started working part-time as a medical officer at Porirua hospital. In those days, there were no house surgeons working in that hospital.

“We did everything—sewed up cuts, treated heart failure and pneumonia—you name it. We referred people we thought needed specialists to Wellington or Hutt hospitals. We dealt with the psychiatric problems as well. So, that’s what I started off doing.”

“I think, looking back on it, the then medical superintendent probably deliberately dropped me in the deep end, thinking that I’d either survive or not, because he was a bit dicey about a female doing only four-tenths. So, he assigned me to the behaviour-disturbed young women, and I think that was my baptism by fire, but I learned a lot. So, after that—seeing as how I hadn’t died or disappeared—he moved me to looking after three long-stay wards; one of them with ‘difficult’ people in, and one of them of intellectually disabled women. I learned a lot from them.”

Now with her family complete and some work experience under her belt, Helen started thinking about postgraduate training. The next Medical superintendent of Porirua hospital, John Hall, played an influential role in Helen’s career path, encouraging her to study psychiatry when Helen and her husband were looking at taking a year’s leave for post graduate study in Dunedin. Helen was planning to do the Diploma in Public Health. Taking his advice, when Helen and her family moved to Dunedin for a year, she studied for a Diploma in Psychological Medicine based at the Waikari Hospital psychiatric unit, while her husband stayed at home at home and looked after the children. With permission to complete the two-year course in one year, Helen was pleased to spend that time studying neuroses, for which she had limited experience. For the research component of her diploma, she applied some of her previous work as a member of a planning committee for children with developmental problems for the Wellington region. This work led to the establishment of Puketiro centre.

“My dissertation was on children with a variety of disabilities, so I looked at facilities they had down there, like the embedded unit at Forbury Park School, where they’ve got physically disabled kids, and looked at what they were doing for intellectually handicapped kids, and so on, at different places, but I also did a research project on school transitions.”

Unlike most NZ psychiatrists at the time who had trained in the UK or Australia, Helen took a different route into specialist psychiatry. After completing her diploma, she returned to work at Porirua hospital and, after further study and experience, additional case studies and an oral exam, Helen was awarded her fellowship with the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists. Three years after returning to Porirua the family moved to Stokes Valley and Helen continued working at Porirua hospital with particular interests in in rehabilitation and resettlement.

“We had a very good Occupational Therapist, and we got a very good rehab unit set up, and we were taking people with a whole range of disabilities, including head-injury, with the aim of getting them back into employment or, in the case of a number of our residents, getting them into employment, by giving them the skills and helping with job placement. So that got going in the 1970s, and that was my particular area of special interest in psychiatry.”

Rising up the ranks: superintendent, Chief Medical Advisor, & Commonwealth Secretariat at Health Division

During her time working as a psychiatrist, Helen never lost her special interest in public health and the systems-wide approach to medicine. In the late 1970s, when the Department of Health began encouraging senior health workers to complete further training in health administration, Helen took the opportunity to study for a Diploma of Health Administration at Massey University, graduating (with distinction) in 1981.

In 1982 she was appointed Medical Superintendent of Wellington Community Health Services, a half time position in which she worked with the Principal Nurse and a Director of Administration in the triumvirate which was the management structure at that time. When the medical superintendent of Porirua Hospital left in 1986, Helen was appointed.

Helen found herself in senior management roles during a period of reform during the 1980s, when New Zealand’s health system restructured into 14 Area Health Boards. When she applied for the role of Superintendent-in-Chief of Wellington Area Health Board in 1988, an almost overnight change in management structure landed her instead in the role of Chief Medical Advisor to the new General Manager. The change was from a triumvirate of Medical Superintendent, Chief Nurse and Director of Administration to a single General Manager with the clinical leaders at the next tier. The new system had a number of flaws, in Helen’s view. These included a lack of cohesion between the different health boards, competitive contracting in of services, a policy of buying in new staff rather than succession planning, and dividing the Wellington area into two District Health Boards. Helen found she and the Chief Nursing adviser had less power in their new roles to influence these changes. During this period of change Helen was involved in some national committees, such as that on ‘cross boundary charging’ in preparation for smaller Boards receiving population based funding and buying secondary and tertiary services from larger Boards that could provide such services.

“On that committee, I suggested an alternative would be to fund the big boards for the entire population they’re doing all the tertiary services for, and then the smaller boards would be just funded for their primary and secondary. I was told “that’s not what they want”. I think we might have snuck that in as an option, but it was totally ignored, and our brief was that this is the way it’s going to be, and never mind that you’ve got a more economical idea. So, that’s the way it went.”

Also, during the 1980s Helen pursued her interest in population health and did further study including ad personam study to become a member of the new NZ College of Community Medicine (now the NZ College of Public Health Medicine).

In 1990 the Area Health Board General Manager drew Helen’s attention to an advertisement from the Commonwealth Secretariat looking for a Deputy Director in the Health Division, and she decided to apply. Her application was successful, and she and Ron moved to London in October 1990. This opportunity saw Helen heavily involved in international population health, including yearly responsibilities for a one day meeting with the Commonwealth Health Ministers the day before the World Health Assembly, and organising major Health Ministers’ meetings every three years. Conference topics included Environment and Health, Women and Health, alcohol, HIV/AIDS, and immunisation.

“Oh, it was great. Well, I saw and heard from countries in Africa—a very different view of HIV/AIDS, from that being pushed particularly by the US, which had a strong influence on WHO. The Commonwealth was really the only major voice that was saying, “this is hitting everyone”. Things like blood transfusion services, like transport routes; these things are all important, and these were things we did studies on, and shared the information.”

Helen returned to New Zealand in mid-1996. With insight from six years overseas working on international projects, Helen now knew that she did want to look for a role of General Manager. She was particularly disappointed by the lack of progress in developing an integrated health system since she had been away.

“By then I’d realised quite clearly that I didn’t want to be a General Manager—working out your objectives, and going hell for leather for them, etcetera. Never mind about what happens on the way. Of course, by then we’d seen it; we’d seen the Roger Douglas approach, and so forth. I was much more aware that things were far more complex, and that you might get from A to B, not that way, but by quite different ways.”

“I realised that a lot of the computerisation that I’d seen happening at the end of the ‘80s—like in Dunedin where they were able to pull together data on someone who’d been having heart surgery, and how they’d made out and all the rest of it, and I thought, well this is great—people have been moving forward… I came back reasonably computer literate to find that New Zealand was in chaos, and that we didn’t have a linked-up system, all the Boards were going it alone, and that systems didn’t talk to one another. I was quite appalled at what hadn’t happened in the intervening time, knowing what could have happened.”

Helen found it difficult to integrate back into New Zealand’s health policy landscape. Instead she spent time with family—her mother who was still alive, and her grandchildren.

“I made contact with people I actually knew at the ministry, and picked up no interest whatsoever, in anything—not even in a debrief. There was just no interest, and by then, I had served on international committees and been involved in some quite big stuff, so looking back on it, I realise that probably I could have been more active in getting involved, and in fact some people thought I might have gone for international projects, but by then, we were home, we had grandchildren and there were a lot of things at home that we wanted to pick up on.”

Helen moved into a new phase of her career with part time work initially in the CRHA and then with the Ministry of Women’s Affairs, where she wrote a paper auditing cervical screening in New Zealand. She found this particularly interesting, despite the sensitivity issues.

“The business at Gisborne had blown up—screening not happening properly—and there was a serious question about it, so I was asked to write a paper on it for the Ministry of Women’s Affairs.”

“I got access to the basement at the Ministry of Health, to look at what papers they had there. I used the WHO standard for cervical screening, and measured New Zealand and its progress. We came out very badly, because we’d made some serious mistakes with the restructuring, and had actually re-structured out some of the expertise, and had failed to pick up quite a number of things. So, on my very simplistic chart of what we were doing, as against the WHO standards, we didn’t come out very well. So, they came back to me from Women’s Affairs management to ask a bit more about it. When they were clear that I had the data there, it went back, and Cabinet still wasn’t very happy about it at all, apparently, which I thought was interesting.”

In 2002, Helen became a founding member of the new Bioethics Council and served on it for four years. “That’s the original one that Government set up to address the cultural, ethical and spiritual aspects of biotechnology, chaired by Sir Paul Reeves. He was great.” After that she became a member of the InterChurch Bioethics Council.

That same year, Helen was awarded a New Zealand Order of Merit for services to medicine.

Helen has continued to attend public health medicine peer group meetings and was involved in the Public Health Association at national level. She was made a Life Member in 2002.

Reflections: influences of others & advice for young women in medicine

“I was never a good housekeeper, and never aspired to be. I don’t think my mother was, either. I employed a series of friends – initially with young children of similar age to our own – to do housework and mind my children. Later it would be someone to do housework and the older teenagers took over dinner preparation after school. I’m often aware that I think the children missed out in various things, but on the other hand, they seem to have done alright, and yeah, we’ve got a good family that sort of rallies around.”

Looking back on her successful career that spanned medical specialisation, health policy and management, Helen reflects how her successes were shaped by the influences of many people along the way—from her earliest influences from home and church, to the teachers and role models at medical school, and the many colleagues and mentors that encouraged her during her career.

“I certainly remember Sir Charles Hercus as the Dean of the Medical School, and his commitment to ensuring that medical students kept their long vacation, because it was the only chance for most of them to rub shoulders with the ordinary people. Then, you remember a lot of the people who lectured, like the Professor of Pathology.”

“Keith McLeod had a much better psychological approach to all sorts of things, than did some of the psychiatrists.”

“Ian Davidson was a psychiatrist at Porirua Hospital, who was always very encouraging when I started there.”

John Hall and Anne Hall—they’re both very encouraging in terms of training and so on. Mason Durie’s another one—he and I were both on the College of Psychiatrists’ National Executive at one time, and he is also influential in public health.”

“I’ve had a lot of good colleagues in public health. Fran McGrath—I have reason to believe she put me up for the Bioethics Council, and she certainly was the one who got me the CRHA opportunity. Then, there were lots of other colleagues—Richard Bush was one I worked under on planning for the Centre for children with developmental problems – Puketiro. Then, there were people like Ellie Garden and Joan McKay who were important in my public health training.”

Despite a high-flying career in management and health policy, Helen recalls one incident that highlights how women were expected to conform to social norms of the time.

“When I was first a superintendent, I’d go to a meeting, and the superintendent in chief found he had to say, “Dr Bichan and gentlemen”. The first medical superintendents’ meeting that Susie Williams, who was medical superintendent at Silverstream, and I were both at, the tea trolley was brought in; Susie and I sat tight. We just sat there, and after a while someone said, “oh I suppose we better get up and pour our tea”. We spoke to one another sometime later, and agreed that we’d sat tight on purpose. After a couple of sessions like that, anybody who got up might offer anyone else a cup of tea, but we didn’t feel free to do that until the ice had been fully broken, and nobody expected us to get up and pour.”

Helen believes that attitudes towards women in medicine have changed, with less need for women’s support groups these days.

“Although when I was in the Area Health Board office, and the Dean invited me to speak to the 1990 medical students intake half the class were women but he had not included the one female associate professor with other members of his staff at the introduction.

Helen can feel proud that she achieved a few of the things she aspired towards when she first dreamed of becoming a doctor.

“The women that went in together, we had the aim of making a difference to people.” When I think of the group who started together and completed the course: Helen Angus as a pathologist, Pamela Brown as a gastroenterologist, Patricia Buckfield as a neonatal paediatrician, Jean Fyfe as a psychiatrist, Tanya Godyaev as a general practitioner, and Anne Gillies and Braida Hopper who joined us, I think all have made a real difference to the people they served.