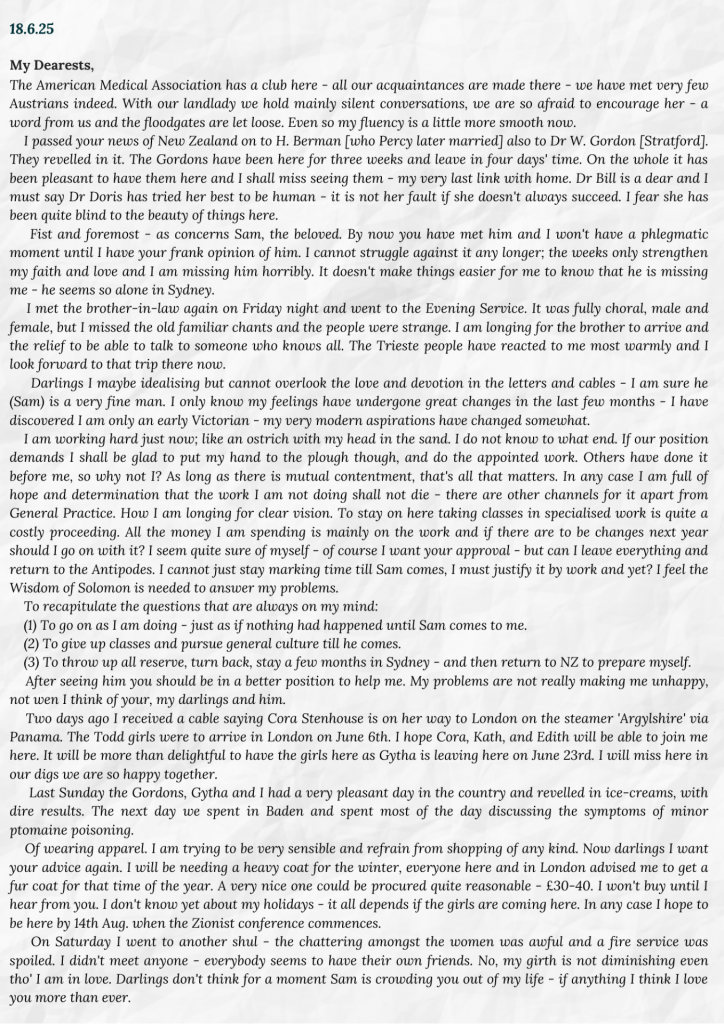

This biography is based on an interview with and material produced by Ann Gluckman. This material includes an interview with Augusta Klippel in 1988. Some of the photographs and all the excerpts are drawn from 840 letters that she wrote weekly to her family in Stratford from 1919 to 1934. These were kept by her single sister Sarah in their original envelopes and were found in 2004, 15 years after Augusta’s death, when the old house was demolished. The interview with Ann was conducted in 2020 for the Early Medical Women of New Zealand Project and the interviewers were Cindy Farquhar and Lucy Goodman. Further resources are listed in the bibliography at the end of the biography.

Contents [hide]

Early life in Tukums, Latvia

Augusta Manoy was born in 1898 in Tukums, a small town not far from Riga, the capital of Latvia. At this time, Latvia was part of Russia and therefore under Tsarist rule, something that would later influence the Manoy family’s decision to move to the other side of the world. Augusta, along with her father Aaron (Adolph), her mother Yetta (née Gerson), her two older sisters Sarah and Rebecca, and her younger brother Joseph, lived in a comfortable, middle-class, upstairs apartment opposite the local synagogue, which Augusta described as a “cosy, refined home although we did not have a great deal of money”. Aaron Manoy was a draper and they always had servants in the house. Due to their close proximity to the synagogue, the family constantly heard singing from the beit midrash (Jewish House of Learning) where students studied the Torah. Augusta also recalled either herself or a servant running across to the synagogue every time a speck of blood was found in an egg to ask the Rabbi if it was Kosher.

Tukums had a very sizable Jewish population. Latvian was the language of the peasants. As the country bordered on what was formerly Prussia, the language of the country was German and many aristocratic German counts had great estates in Latvia. In Kurland, the province where Tukums was located, the Jewish people spoke German as their daily language except for the very religious, who spoke Yiddish. The Manoy family lived in a well-educated area of the Baltic, ensuring that Augusta received an excellent education. She attended an open private school where she learnt subjects such as German, French, Latin, and Russian. Augusta’s childhood in Latvia constantly alternated between feeling safe and fearful. She described her teachers as being “enlightened” and so the Jewish students did not face any fear or discrimination at school. In fact, the anti-Semitism Jews experienced did not come from the Latvians at all, but rather from the Russians. Cossacks, who were mounted troops known for their brutality, were always present throughout the city to ensure that no rebellions broke out. As they marched along the streets they would sing loud enough to remind those inside with closed doors and windows of their presence.

“They sang like angels, those Cossacks, those soldiers, those Russian songs as they marched along. And to wake up and hear that singing and all, it was very cold of course in the Baltic in winter, we always had double windows, double frames, but we could still hear that singing going on through those double windows.”

One year during the Passover, a Christian boy was found dead in the street. Christians in the area blamed the Jews, claiming that they had killed him for his blood. For Jews living in Latvia, “instead of rejoicing, [Passover] was a Festival of Fear … all our doors had to be locked up, you mustn’t make any noise, you mustn’t show any lights.”

One dreadful year, when Augusta’s maternal grandfather was the president of the Shul, during a time of celebration, he accidentally knocked the portrait of the Tsar in the synagogue. The police were called and he was arrested and imprisoned for treason for approximately two and a half years.

The revolutionary years of 1904-5 were difficult for the Manoy family. Early in 1904, Aaron Manoy fled Tukums, as a cousin of his was implicated in the forerunner riots to the 1905 Bloody Sunday Revolt. He first went to England where some relatives had settled after previous pogroms, before moving to New Zealand. Aaron arrived on 18 July 1904 onboard the “SS IONIC”. When in England, he anglicised his name to Adolph, which is the name displayed on the naturalisation paper he gained in 1906. It also displayed his nationality as Russian. When he first arrived in New Zealand, he went to his uncle, Abraham Manoy, who had arrived in New Zealand in 1872 and settled in Motueka in 1882. He had become a prosperous storekeeper and gave Adolph cases of dry goods to sell in hotel lounges and along the rail and bus networks in the lower North Island. Having previously run a draper shop in Latvia, Aaron decided to settle in Stratford, establishing a drapery shop in Broadway. Stratford was the railhead for the new line to connect Stratford and New Plymouth with the main trunk line in Taumarunui.

Adolph hoped to start a new life for the family, as “he could feel that conditions were intolerable for Jewish people.” Young Jewish men were rising up against the Russians and being shot down in the hundreds. Augusta vividly recalled, many months after her father had fled, peeping through the windows from their upstairs apartment, seeing sledges “loaded with corpses, arms and legs hanging out”. Originally, Aaron desired for the family to remain in Latvia as long as possible as the quality of education there was much higher than in New Zealand at the time. However, in 1910, a terrible epidemic of scarlet fever spread throughout Tukums, claiming the life of Augusta’s ten-year-old brother. It was also not until 1910 that Adolph had the money to send for his family. Yetta and the three daughters escaped Latvia “without passport or documentation”. They were first put up on the beach along the Baltic before finding their way to London. There, they obtained passage to New Zealand on the “SS ATHENIC” to start their new life in Stratford. Because Adolph had already naturalised in New Zealand, the family did not require passports or documentation. The passage was stormy and the family travelled in third class. The boat travelled via Cape Town and arrived in September 1910 in Wellington.

“Humble Beginnings” in Stratford

“Deep down there was always that feeling we must get away to a free country and it was always New Zealand.”

By the time Yetta, Sarah, Rebecca, and Augusta arrived in Stratford, Aaron had started drapery store. Augusta described her first impressions of New Zealand as a disappointment:

“After the beauty of the Baltic it was like landing in a desert … because in those days the only beauty you could see in Stratford was Mt Egmont but they had started to burn out the land and all you could see was burned out trees where we were and it was very depressing.”

The early days in Stratford were humble beginnings for the Manoy family. Adolph had obtained a primitive house in Juliet Street which lacked heating, had little furniture and a pit toilet remote from the house. For the first few years, they lived “more or less, on the coal they could pick up beside the railway and odd jobs.” There were only three other Jewish families in the whole of Taranaki and they were all very remote from the congregations with a Rabbi and synagogue in Wellington and Auckland. Despite these difficulties, the family maintained Kosher rules and the Festivals as Yetta was very devout. To get Kosher meat it had to come by train from Wellington. There were no refrigerated vans and the parcel was sometimes lousy when it arrived in summer. Augusta was tasked with collecting the bloody meat from the train every few days. In the end, Augusta refused to go.

“In the end being a strong minded female I objected and I said ‘look Mummy, I want to please you but I am not going to go for those parcels any more nor will I eat any meat’ and she sat down, shed quite a few tears and decided it couldn’t go on and we had to get our meat from Stratford.”

After that, there was only some local meat that Yetta laboured to kosher. They ate mainly fish and poultry as animal proteins. They kept hens and a rooster. Despite the difficulties, it was an observant home which maintained kosher rules and observed all the main Festivals.

When Adolph first settled in Stratford, people assumed he was German because he spoke German. He was naturalised as of Russian origin but he loathed Russia. Stratford was a rural town and few people would have known where Latvia was. He arrived at a time when New Zealand feared Russia and believed the Russian White Fleet might make an attack on Auckland. Gun emplacements had been erected on Mount Victoria and North Head as early as 1885. When war broke out there was antagonism against all people of German origin in the district, including the three other Jewish families in Taranaki. Augusta sat German as her subject for Matriculation in 1914. Enrolment had been made before the war started and she gained a mark of 96%. These marks, along with all matriculation results, were published in the newspaper. In the first year of the war, attacks were made on the Manoy’s shop and a large public meeting against the Germans took place on the steps of the Town Hall. It was only when Reginald Manoy, a cousin from Motueka, was killed on the Somme in 1916 and his name was on the weekly list of casualties posted on the Post Office wall that Augusta felt she could hold her head high. After this, no local policemen were needed to prevent assaults on the family.

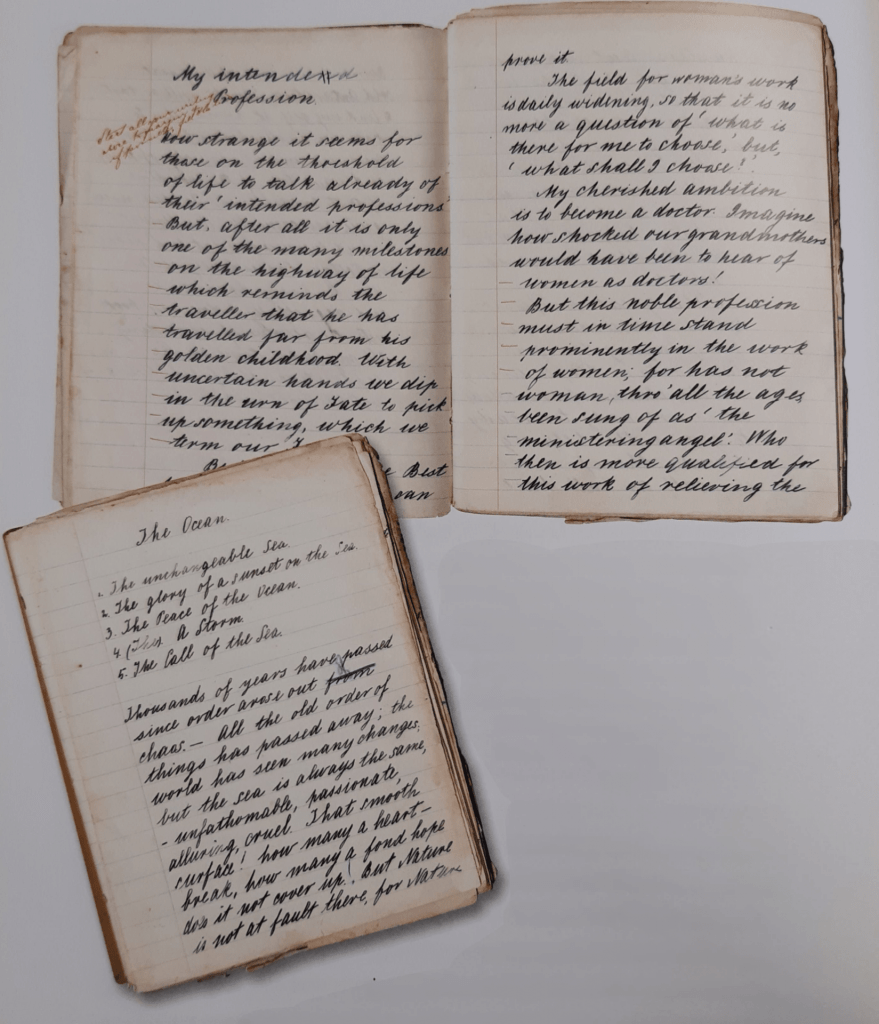

The Manoy family had no knowledge of English before travelling to New Zealand. Augusta endeavoured to learn it on the boat from England and mastered the language by the end of her first full year in school. Indeed, the three girls “insisted that only English be spoken in the home as soon as they came to Stratford.” Augusta’s mastery of English can be seen in her essay entitled ‘My Intended Profession’ where she outlines her desire to become a doctor. She wrote this essay the year she sat for Matriculation.

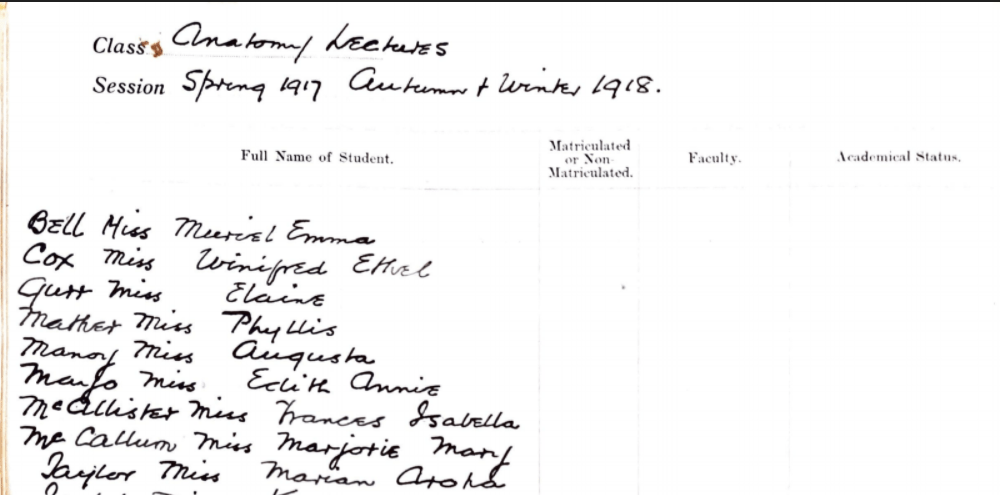

At the age of thirteen, Augusta entered Stratford District High School. As her English was at a low level upon arriving in New Zealand, she was originally placed in Standard Four, though the next year the headmaster promoted her to Standard Six when he recognised how well-educated she was. At this time, Stratford District High was similar to a technical school for “children of local farmers and people connected to local shops or the dairy industry. Most children left with a Proficiency Certificate.” Augusta, however, received the Senior Board Scholarship after her final year at school, which was two years after Matriculation when she had turned 18 and sat University Entrance examinations, making history in Taranaki. The scholarship ensured that her schooling and books were free and it came with a stipend of a few pounds every quarter, which she saved for her later education. During her time at school, Augusta met Frances McAllister (later Preston), the daughter of the local photographer who would also go on to medical school with Augusta and eventually graduated together. Frances and Augusta were always competitors rather than friends. It is amazing for two girls from a country District High to get into Medical school in the small 1917 intake.

Studying at the Otago Medical School

Augusta’s family were “horrified” to hear that she wanted to become a doctor. Traditionally, the youngest daughter in a Jewish family would stay home to look after the ageing parent. “Her father reluctantly gave way, but told her that one failure would mean the end of her education.” Despite their disapproval of her chosen route, Augusta’s family financed her to attend the medical school and assisted with other monetary necessities, such as clothing. Augusta entered straight into medical school after finishing high school in 1916, only coming home to visit her family in the summer holidays. She and Frances McAllister were two of six women in the small 1917 wartime intake.

Augusta attended St Margaret’s College, which was a Presbyterian residence, and the only female residence for the university. She was the first Jewish student to reside here and managed to obtain permission from the matron, along with two Roman Catholic girls, to only attend Old Testament prayers and readings, despite constant threats by the university to dismiss her if she did not attend New Testament meetings as well.

The first year of medical school was difficult as Augusta had not learned any science at high school apart from a few lessons on heat. She had received admission to medical school due to her proficiency in Latin and spent the first year catching up on the subjects she had not previously been exposed to. Indeed, being a woman in medical school proved difficult in other areas as well. Some teachers and classmates disapproved of women studying medicine and so Augusta had to be careful not to cause “offence or criticism”. The women were expected to sit separate from the men and Augusta recalled one lecture given on contraception where the “ladies were asked to leave the room as the subject was suitable only for gentlemen.” Moreover, women medical students were not eligible to gain membership to the Medical Students’ Association, “as smoking could not be enjoyed in their presence.” Reflecting on her time at medical school with Augusta, Frances Preston (née McAllister) wrote that the social background Augusta and Frances grew up in in Stratford was “Victorian” and ill-prepared them for university life.

“Their upbringing did not foster independence or encourage individuality; they were not taught to think for themselves; they learned only what their teachers taught them and did not delve deeply into.”

Despite these challenges, Augusta quickly became recognised for her diligence and intelligence. In 1919, she received a pocket case book inscribed with “Presented to the Keenest Lady Student in Dr Barnett’s Class, Miller Ward 1919.” She also had a very active social life. She described herself as “quite the character” in those days. When word came through that the Armistice had been signed following the war, “we were celebrating it in the Octagon and I who am absolutely tuneless who can’t sing God Save the King stood up. There is a fountain in the Octagon … in Princes Street near to the Stock Exchange. I clambered up on that thing and conducted the ‘Marseillaise’.”

At weekends she often went on drives with Kathleen Todd, who owned a car. She received many invitations from local students with family in Dunedin and she greatly enjoyed and learned much of the best of English social mores on visits to their cultured homes.

At the end of her second year, the influenza epidemic broke out, finally arriving in New Zealand in October 1918. By November, the epidemic broke out in Dunedin – shortly after news came that the Armistice had been signed – and the second-year medical students were asked to work in the hospital. Augusta requested to attend to the Plunkett ward, which was the male ward – she did not know that it was going to be the worst ward. “It was the most tragic six weeks … Night after night, I can’t tell you what it was like, it was like a plague. The horror of it. Well we just stuck it out.” At the end of the holidays, Augusta came down with the flu quite badly. Unfortunately, St Margarets was closed and she refused to go to the public hospital. Sir Lindo Ferguson ended up taking Augusta and her colleague in so he could look after them. Augusta developed partial alopecia and lost much of her hair. Despite this, she recovered and managed to get home to Stratford to see her family at the end of the holidays. Augusta and her colleague, Valentine, were recognised for their efforts during this epidemic and, when travelling back to Christchurch for university, were given access to the vice-regal compartment of the train, which was the Governor General’s coach, as a special reward. She was also sent a letter from St Margaret’s Board stating that she was “free to do as you wish as regards prayers.” Commenting on this, Augusta stated that “they couldn’t help it because I mean there would have been an outcry from all the students if I had been shot out after they saw how one toiled and all.”

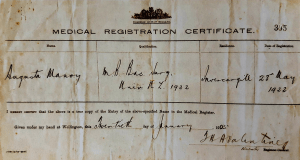

Augusta was an extremely talented student and was never held back. She did miss one paper and had to stay in Dunedin to prepare for specials in Surgery, which she did not enjoy, early in 1922. In 1922, when Augusta graduated with her medical degree, she became the first Jewish woman doctor to graduate from the Otago Medical School. Unfortunately, her family could not attend her graduation due to the great distance between Stratford and Dunedin and Augusta must have gone home to await finding a position.

Early Career in New Zealand

Nearing the end of her studies, Augusta began to worry about obtaining a job. By this point, the men who had fought in the war were starting to come back to New Zealand and they were given priority. Furthermore, it was difficult to get a position as a house-surgeon, as each hospital only had between five and six positions available. Women doctors also faced extreme discrimination when searching for positions at the completion of their studies. For example, Augusta claimed that Sir Frederic Truby King (known as Truby King) wrote to all women who applied for a job at Karitane Hospital until his retirement in 1927: “I do not approve of women medicos … It’s your job to get married and produce bonny babies.”

Augusta was offered a position in Dunedin and Rawene. She accepted neither position though, as Frances McAllister advised her not to take the job in Rawene and Marion Aroha Radcliffe-Taylor said that she could not leave her single mother in Dunedin alone and so requested that Augusta turn down the offer so that Marion could take it instead. “Being very impulsive I said alright, I will step down.” Through Charles Burns, Augusta obtained an assistantship in Takaka under Dr Woodward for eight months. Life as a rural medical practitioner was difficult and lonely. Dr Woodward described Takaka to Augusta before she began her position there, commenting that “There are plenty of amusements… but the average person – well, it’s impossible to make a pal of them like we used to have pals in varsity. They only gossip and make mischief.” Furthermore, within the eight years Dr Woodward had practised in Takaka, he had only had time to take one holiday. With Augusta joining the practice, he hoped to “make some scheme to work upon as regards being on duty so that each may be certain of having a ‘Spell’ off duty … It is not the actual amount of work that kills. It is the horrible sensation throughout the whole 24 hours that one is likely to be called upon at any minute.” Despite describing her eight months in Takaka as “hard work” and a “rough practice,” Augusta claimed that she “learned a tremendous lot.”

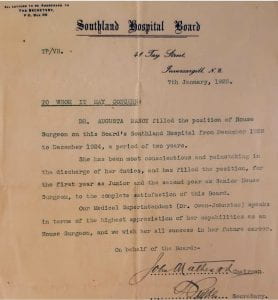

Towards the end of 1922, Augusta received a notification from Dr Owen Johnston stating that there was an opening in Southland Hospital, Invercargill, for house-surgeons and they were considering women doctors. The position would begin in November and the term was for two years. Both Augusta and Frances McAllister applied for the position but Augusta was given the position.

She regularly travelled to Bluff at weekends to administer injections of neoarsphenamine or Salvarsan to visiting syphilitic seamen and looked after the townsmen who walked across the bridge to the nearby brewery on Saturday nights to escape the prohibition in town. The workload was challenging and the superintendent took every opportunity to conduct surgery on his patients, even when Augusta did not think it wise. She had a “marvellous time” in her two years at Southland Hospital.

During her time in Invercargill, Augusta worked long hours and did not socialise much. The standard was to work until midnight. She could not maintain many Jewish observances as there were no Jews in Invercargill and these observances weakened over her seven years away from home for all the main festivals, but she remained culturally and philosophically strongly true to her roots throughout this time. There were also strong social divisions between people of different races, religions, and class. Augusta would not consider marriage to a non-Jewish man as it was considered a tragedy in Jewish families for a child to marry ‘out’ but there were no Jewish men in Invercargill. She even did not go to social dances, potentially because she was afraid of forming an attachment with someone, she could not pursue a relationship with. Moreover, she would not consider an arranged marriage.

Despite not being able to find a romantic relationship during her time in Invercargill, August developed a platonic but deeply personal friendship with Dr James Young. Dr Young was born in County Down, Ireland, in 1856 and graduated from the Royal College of Surgeons in Dublin. In 1887 he settled in Invercargill but was an examiner at Otago Medical School and he lectured on special aspects of historical medicine. Augusta and another student were invited to afternoon tea in December 1922. In a letter to her family, Augusta described Dr Young as:

“… one of the most cultured men I have come across. He has the rarest and most wonderful collection of books I have ever seen. French, German, English, all stand shoulder to shoulder – old prints, first editions – I just revelled in it all … Altogether a perfectly charming personality.”

Dr Young fostered in her a love of the history and culture of medicine, and he shared her love of Latin and English Classics, European poetry and music. He introduced her to Sir William Osler’s Aequanimitas which defined the qualities of a good physician, and Browne’s Religio Medici, both of which were by her bedside when she died.

After Augusta left New Zealand their erudite correspondence continued. Ann, Augusta’s daughter found 18 of his letters wrapped in a silk bag in her dressing table drawer after her death. In a letter to her in Vienna dated 22 July 1924, writing in German he quoted the Viennese pioneer of thoracic medicine, Josef Skoda at length. Dr Young was her role model as to how to lead a refined, dignified and thoughtful life. This friendship lasted through their correspondence until he died in 1940. Dr Young treated Augusta as an intellectual equal which boosted her confidence as a female doctor when faced with discrimination and anti-Semitism.

Postgraduate Studies in Vienna and Meeting Samuel Klippel

After two years in the position at Southland Hospital, Augusta decided to move to London in the hopes of pursuing postgraduate studies in paediatrics, a topic that had extremely fascinated her during her degree. Augusta set off for London, crossing from New Zealand to Sydney on a Trans-Tasman ship. She had to wait several days for the “SS MOOLTAN”, which would carry her to London via the Suez Canal. During the stop-over in Sydney, she stayed in the home of Mr and Mrs Kahn, who were family friends from Tukums. Mr Kahn had a business associate, the handsome young Samuel Klippel. Augusta wrote, “I stopped in Sydney and that’s where I met my husband-to-be. There is a destiny that shapes our ends.” Augusta and Samuel spent ten hours together before she once again boarded the ship and set off. When the boat stopped in Melbourne she received a radio-message from Samuel saying: “will meet you in Adelaide, I’m coming by train.”

Samuel and Augusta reconnected in Adelaide and he proposed to her, asking her not to go further. “I said not on your life. I worked eight years at medicine and I’m not going to abandon it now.” And so Augusta carried on to England, leaving Samuel behind in Australia.

Upon arriving in London, Augusta applied for a position at all the hospitals she could, including the Jewish Hospital. Many responded with the excuse that “they hadn’t room for women to do post-graduate work.” After many months of failed applications, Augusta heard that Dr Sylvia Gytha de Lancey Chapman, who was to become her lifelong friend, was going to Vienna to study obstetrics and gynaecology, specializing in paediatrics. Austria is a land-locked country and during World War One, the diet was very restricted for nutritious food.

“After the war it was the ideal place to study children … who hadn’t had the proper nourishment and all, whose mothers had gone through hell.”

During her time in England, Samuel bombarded Augusta with radio messages asking her to come back. She finally agreed to come back after the fruitless attempts in London to get a job, however, there were conditions attached. Firstly, she wanted to go to Vienna to complete her postgraduate studies. Secondly, Samuel had to go to Stratford to formally ask her hand in marriage and receive her family’s approval. With that agreed upon, Augusta started her postgraduate studies in Vienna alongside Dr Chapman, where she met some “outstanding Jewish professors” as well as von Pirquet who was well known for his groundbreaking work on tuberculosis and deficiency diseases. Augusta was “entranced by the sophistication, wealth, and prestige” of the people she met in Austria. She received a Certificate in Paediatrics from the American Post-Graduate University in Vienna 1926

Concurrently to her enjoyment of her studies, Augusta found Vienna to hold an intense level of religious prejudice. A new anti-Semitic movement was developing that quickly turned racist. “As nationalism flourished, Jews, as outsiders, were seen as a threat by extremists who were looking for scapegoats for economic problems.” Augusta intensely hated war and bloodshed and found the suffering of the world due to recent global events difficult to witness having come from relative peace in New Zealand. Her views were relatively liberal for a Jew and aligned more with the father’s than her mother’s. While in Vienna she attended the Zionist Conference, which profoundly shaped these views.

“People (Jewish) from all around the world attended … it was the most stirring thing you have ever known. I mean it was so great and you felt there was going to be a marvellous future for us … I am afraid they have let us down I know we are small and have got to be defended and all, but it has done us a tremendous lot of harm.”

The Zionist beliefs Augusta developed in Vienna greatly shaped some of her activities in Auckland She played a significant role in the Women’s International Zionist Organisation (WIZO), raised money for Hadassah Hospital in Jerusalem, and baby care organisations in Palestine and Israel modelled on the Plunket Society.

The entire time Augusta was in Vienna she received letters from Samuel asking her to return to Australia. After six months, Samuel Klippel’s brother, Alec, came to Vienna requesting her to return and marry him:

“He said look here, what are you doing, you’re driving him crazy, because by that time they were partners, and he said he can’t settle down, he can’t do anything. And I decided by long correspondence and all that he was the man I wanted.”

Returning to Australia and New Zealand

At the end of 1925, Augusta left Vienna and sailed from London to Adelaide. She went by train to Sydney where she spent a week with Samuel so she could get to know him better. Then she returned to Stratford, followed by Samuel, so he could receive approval from the family. On 11 February 1926 Samuel Klippel and Augusta Manoy were married by the Reverend Pitkovsky in the garden of the family home. Only family were present and the ceremony was held under the traditional chuppah (Jewish wedding canopy). After the wedding, the two caught a train to Wellington, incidentally in the same carriage as the Reverend Pitkovsky, and the next day they were on a boat back to Sydney. The couple settled in Roseville where Augusta worked in several hospitals. In her interview from 1988, Augusta commented that she was “still ardently Jewish and all and determined to go on with my medical work.”

Soon after settling in Sydney, Augusta was introduced to Dr Fanny Redding, who was a well-highly- regarded physician and an ardent Zionist. Fanny was considerably older than Augusta and took her under her wing. She introduced Augusta to many of the leading medical people.

Starting a Family, Sickness, and Community Involvement

Augusta obtained a position in Camperdown but unfortunately had a small collision with a tram. After that, she did not drive again until she and her daughter, Ann, learnt to drive at the end of 1944. On the tape she recorded, Augusta stated “I started going to hospital and to work and there was my dear husband waiting for me in the car and I thought no, this cannot go on. And I wanted a child, I was then 28, time was moving and I thought I am going to have children first and then go on. Anyhow, I got ill and that finished my medical thing.”

In late August 1926, Augusta had a miscarriage after suffering an ectopic pregnancy. One week later she was operated on for peritonitis. Four months later, Augusta became pregnant again with Ann. The couple left for Europe and England in April 1927 and were renting an apartment in London as a base while Sam was buying silks and other textiles for the firm “Klippel Bros Ltd.”, which manufactured ties. At this point, Sam was in partnership with his brother Alec.

Their daughter, Ann, was born in London after an emergency caesarean section in London. They returned from London in December 1927 accompanied by a nanny. The ship’s first port was Wellington and Sam left Augusta with the family in Stratford so that she could recuperate. He continued to Sydney and returned to take her home with him to Sydney at Easter, 1928. On 2 January 1930 in Sydney, Augusta gave birth to their son, Geoffrey, again by caesarean. After this, Augusta was very frail and never returned to medical practice.

Until the move back to New Zealand in 1934, the children were largely looked after by the Nanny. In August 1934, when they returned to New Zealand, they settled in Auckland. It was Dr Kathleen Todd who found them a house to rent at 76 Lucerne Road, Remuera. They later bought the house. Augusta improved in health after they came to Auckland, without the nanny, but they employed a live-in maid. Augusta became a pillar of a Women’s Reading Club, where women discussed English classics many years before book clubs became very popular. She adopted the upper-middle-class custom of not being hands-on with Ann and Geoffrey but took a great interest in their education once they reached Secondary School.

Samuel was quite traditional in his understanding of what a married woman should be doing. Samuel believed that “it was a Jewish man’s role to provide for his wife and family” and Augusta actively supported her husband when he held work and social events at their home. She commented that they often had emissaries or meetings of 30-40 people in their home due to Samuel’s role as president of the Zionist Society in the late forties and early fifties

Augusta also remained very socially active. Due to her relationship with Kathleen Todd, who came from a hugely sought-after family, “Augusta became part of the creme de la creme of the social set in Auckland.” From these friends she certainly learned to keep a stiff upper lip in public, even on very sad occasions. She was the president of the Auckland Medical Branch of the Women’s Medical Association for three terms and the Union of Jewish Women, a foundation member of the Friends of the Deaf and the Ellen Melville committee, and raised funds for the hoped-for National Women’s Hospital on the slopes of Maungakiekie. Augusta played a “significant role in the committee organised by Doris Gordon to raise money for the National Women’s Hospital” and she was “very much a mentor for young medical women.” Notably, Augusta “rejoiced when changing mores, in the post-war years, allowed women to rear families yet continue in active practice.”

In 1952, the Klippel’s flew to London and Europe on a business trip, basing themselves in London. They travelled to Italy to visit Sam’s oldest brother, Henry, then to Milan and then on to Vienna, where Augusta hoped to locate the lady in whose home she boarded during her postgraduate studies. It was a distressing time for Augusta, as she found that she, and many others whom she had met, had perished in the Holocaust. Upon their return to England, Sam had his first coronary. The couple returned to New Zealand by ship and Sam continued at work for the next twelve years, with Augusta watching over him very carefully. In 1964, Sam decided to sell the business as his only son, Geoffrey, did not wish to take it over. In October 1964, Sam passed away at home in his bed on the day the business was handed over.

Augusta continued to live alone in the house on Remuera Road for another 25 years, maintaining her independence, her vitality, and her intellectual brilliance to the very end of her life. She became known for her delicious baking, her aptitude at Bridge, and her to-the-minute knowledge of current affairs. She subscribed to the New Zealand Medical Journal and kept her Medical Registration up to date – it was still current at the time of her death. She prescribed her own medications but she would never write a prescription for anyone else.

Death and Legacy

Augusta made it her lifelong goal to ensure that she, and in their turn, her family, were true New Zealanders who truly appreciated “the wonderful freedoms it offered.” On 05 October 1989, Augusta Klippel passed away from kidney failure at the age of 91. She is survived by her daughter Ann, her son Geoffrey, and their children.

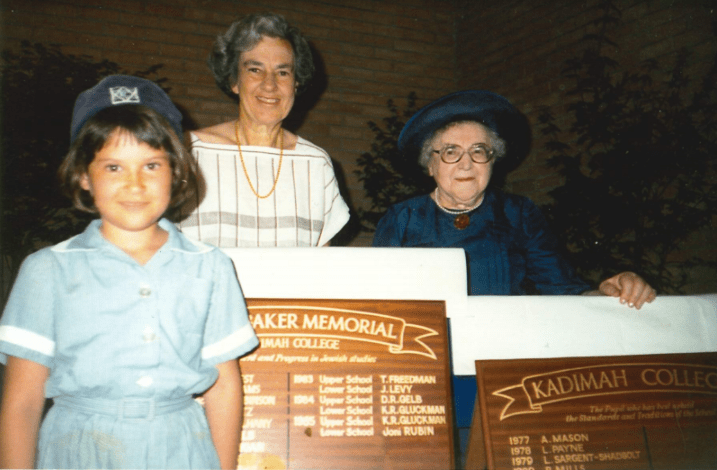

She lived to see Peter Gluckman, her grandson, appointed Professor of Paediatrics at Auckland Medical School and Philip Gluckman graduate an MBChB. She had much contact with both, always asking them about medical-related issues.

“She was [a] benevolent staunch friend, thoughtful listener, fascinating conversationalist, good advice giver, ran a beautiful, artistic home, was hugely clever except at maths, a wide reader a wonderful letter writer, a shocking driver, a lover of high heels, a wonderful worker for medical causes, beautifully dressed, lover of her garden, a passionate Zionist in the founding stages of Israel and supported Hadassah Hospital in particular. She took the best of English culture and was passionate about reading wisely, a wide range of current books and listening to Classical Music – and watching “Coronation Street” on television in her bedroom. To the day she died she had a keen interest in world affairs and thirty years on she is till keenly remembered by many .”

Bibliography

Augusta Klippel interview by Shirley Ross, 1989, Auckland Jewish Oral History Project, Auckland Libraries Heritage Collection, OH_1434.

Gluckman, Ann, Dr James Young: A Thwarted Medical Historian, Paper delivered to Auckland Medical Historical Society, 2010.

Gluckman, Ann, Identity and Involvement: Auckland Jewry, Past and Present, Dunmore Press: Palmerston North, 1990.

Gluckman, Ann, Postcards from Tukums: A Family Detective Story, David Ling Publishing: Auckland, 2010.

Gluckman, L. K., Obituaries: Augusta Klippel, New Zealand Medical Journal, 13 December 1989, p.656.