This biography is based on an interview with Judy Barfoot in 2016 for the Early Medical Women of New Zealand Project. The interviewer was Claire Gooder.

Contents [hide]

Early life: growing up on a farm

Judith Anne Radcliffe (Judy) was born in 1936 in the Bay of Plenty and spent her childhood in Edgecumbe and Whakatane. She and her younger sister grew up on a sharemilker farm (meaning that the profit was shared between their family, who owned the farm, and others who came to milk the cows). Her family also owned two other farms; one across the railway which had sharemilkers, and a sheep farm at Pikowai. Her father worked on the farms while her mother looked after the family and cooked for various people who would come along, including hay-makers and shearers. Judy liked growing up on a dairy farm as she enjoyed being outdoors. She and her sister did not do much work on the farm, aside from a small amount on the sheep farm. “We weren’t allowed in the cow-shed, because we had sharemilkers, and they didn’t want kids rushing around being a nuisance; not the boss’ kids, anyhow.”

Judy spent one year commuting to Whakatane High School while living at home. The bus ride was one and a half hours each way, meaning that “in the winter I’d leave home in the dark, catch the bus which took forever going right round the back road, and then I would get back in the dark.” Her parents thought that this was too much travelling for her, so the next year, they moved her to Solway College, a boarding school in Masterton. “First term, I suppose I was a bit home-sick, but after that, no, I loved it.” Judy appreciated the newfound time in the afternoons which was no longer wasted on the bus ride, and she took up some extra-curricular activities, particularly sports. She also enjoyed the social aspect of boarding, especially as living on a farm had made it difficult for her to see her friends outside of school time. “It was easier to make friends, because you were all there; that was the other good thing about it. When you’re on a farm, your friends are one or two miles away, walking along a gravel road, and while I could have gone to see them, I never did, and they never came to see me, either.” As Judy knew that she wanted to go to university (though she had not decided on medicine), she took her work very seriously. “Not many of them did [go to university]; not many of the girls did, because they were going to go home and get married.” Judy has kept in touch with some of her school friends, and still occasionally sees her best friend from school, Sally.

The decision to go into medicine: supported by parents who valued education

No one in Judy’s family was in the medical field. She is not sure what influenced her decision, but she believes that her parents were key, as they both valued education and wanted their daughters to succeed. Her father, whose parents had moved around a lot while he was growing up, had not had much of an education but he was a stretcher bearer in WW1 so saw a lot of trauma and medical events. Judy’s mother was a teacher. Thus, though they came from different educational backgrounds, Judy’s parents were united in the value they placed on education, and in their desire for Judy to be successful – particularly as Edgecumbe was a small place and very few girls from there went to university.

Medical intermediate: struggling due to her minimal science education

Judy went straight from school into medical intermediate at Otago in 1955. She clearly remembers the excitement of leaving her parents behind and embarking on a new adventure with her best friend, Sally (who did not go into medicine). “Oh, we were so excited. We were just so excited to get away from boarding school, and our parents, and everything.” She stayed at St Margaret’s College for her first three years in Dunedin. Although the Hall was rather restrictive (residents had to be in by 10 pm) and the meals were not wonderful, Judy liked being there “because of the fact we were all there together.” While there, she socialised with women from many different courses.

Like many women at the time, Judy had received insufficient science education, so she struggled with the medical intermediate year. Her secondary school had not had a physics teacher, and though she could have done biology (which was similar to zoology), she had chosen instead to do the subjects which other girls took: Latin and French. “Oh, [entrance into medical school] was sitting intermediate, and I was a bit unlucky in a way, because I’d been to a girls’ school, and we just did languages and I think chemistry, but I hadn’t done physics and I hadn’t done zoology. So, it was a really hard year for me.” Although she struggled this year, she did well enough that she was able to progress into medicine the next year.

Medical school: a long time studying

Judy entered medical school in 1956 with very few expectations, as she had no idea what the course was going to be like and she did not yet know what area of medicine she wanted to pursue. She soon found out that she was not going to love every aspect of the course. “The beginning was just all lectures, and an awful lot of anatomy, which I hated.” Since Judy did not enjoy anatomy, it seemed to her that they spent too much time doing dissections. “It was far too much time, and I wasn’t any good at anatomy. I didn’t know what was going on, I don’t think. I didn’t quite realise I had to learn all the nerves and bones and all this sort of thing.” They were in groups of six students to each body. Judy’s group had three women and three men; the women worked on one side while the men worked on the other. Unlike Judy, Glenys Arthur (nee Smart), knew a bit about anatomy and was very happy to dissect things. The first test Judy ever failed was anatomy at the end of the first term, in which she scored a 29. After this, her boyfriend assisted by giving her some help, and her anatomy knowledge improved. Anatomy was taught by Professor Adams but some of the women students felt picked on and that he did not like them very much.

Judy did enjoy some subjects which they studied, particularly physiology and physics. She also liked the clinical side of the course, although this was very limited until about their fifth year. The students were allowed to go to Accident and Emergency (A&E) to observe and help. Judy remembers that her classmate, Alison Sommerville (nee Knox), did this, but Judy and the other women did not. The only practical experience which Judy really got in her early years was watching registrars interview patients.

While they were in Dunedin, Judy had to spend quite a lot of time studying. It was common to spend a few evenings each week studying; students from all courses did this, not just medical students. Judy did not do many extracurricular activities, although she did join the tennis club for a while. She tried tramping with Sally, but once was enough for her. “It was pouring with rain; we just walked up the top and walked down again. I thought, well this is tramping? I didn’t go back; believe me. It was a shame really, because I belong to a tramping club now.” The students did not tend to travel around Dunedin much, as bikes were their primary mode of transport. “We went to the Medical School, and occasionally went around the peninsular, but we didn’t go very far at all. I mean, I doubt if I ever went to the Octagon, as a student; we had no money and there was nothing there for us.”

The cost of Judy’s tuition was partially covered by a bursary, and the rest came from her father. She tried to work during her summer breaks, but did not enjoy most of this work. One year, Judy’s mother found her a job at a dress shop, but Judy hated dress shops. Since she was so bored, she spent her time reading a book under the counter. Her boss was not very happy. She also had some other jobs, including at Whakatane Hospital and as a waitress at Kawau Island. None of the jobs paid very well, so she did not have much expendable income. The male medical students were generally able to get better-paying jobs in the summer at the freezer works, so they had more money to spend.

As most of her money was coming from her parents, she did not go out much. “My parents were paying for me to do everything in medicine and a bit more; you had to get a microscope and you had to buy all these books, so you didn’t really expect them to pay any more.” In Judy’s opinion, “there wasn’t a lot of social life,” because they did not have the money. They did have a small number of parties in wool barns, in which the male students tended to get drunk. These ‘bashes’ were the only time they would get alcohol; the men would drink beer and the women would have a glass of Pimm’s. On the whole, alcohol was not a big part of student life. “No, it wasn’t a feature, getting drunk, at all.” Smoking was not a big part of their university experience either, once again because they could not afford it.

In Judy’s fourth year (1958), she flatted on Castle Street with another medical student, Heather Leslie (nee Mcallum), an Arts student and a Home Science student. The latter was “the worst cook” they ever had. By the end of her week cooking, the other girls never had anything nice to say about her.

Unsurprisingly, the next year the home science student was no longer in their flat. Instead they moved to another flat where Ailsa Morrison-Galt (nee Smith) and Ngaire Jeffries (nee Twose) joined them. By this stage, most women their age had graduated and were no longer living in Dunedin.

Judy went to Auckland for her sixth year of medicine (1960) because it was nearer home. There were a few other students who went with her, one of whom was Jon Simcock. Judy was lucky that a family friend (who was not a medical student) had a spare room in a five-person flat on Grafton Road, right above the hospital. In Auckland, she was exposed to more specialties than in Dunedin. They did still have lectures, but they also had patient contact, making it more clinical than the time in Dunedin had been. If house surgeon positions became vacant, the sixth years were able to fill in, and they got paid for doing these runs. When Judy reached this stage in her training, she “finally sort of felt [she] was doing something.”

For Judy, the main struggle of studying medicine was how long it took. Other aspects of the students’ lives were delayed as a result, such as getting married, having families and travelling. Most of her friends finished their degrees in three years and were doing their overseas experiences (OEs) while the medical students were still studying. “Oh, by that time all my other non-medical friends had gone overseas on their OE, which I found quite difficult, actually. I thought, we’re never going to finish this.” By the time she did eventually finish studying, she was very sick of lectures!

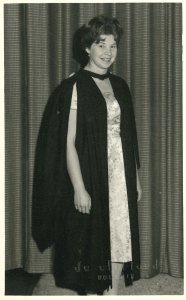

A key achievement of Judy’s career was completing medical school. She went back to Dunedin for her graduation in 1960, and graduated alongside 15 other women. Her family did not accompany her for this as it would have been difficult for them all to get there (planes were expensive, while cars and trains took a long time). For this occasion, she bought herself a very expensive pair of high-heeled shoes which she wore as she “tottered” across the stage. They probably cost half the money which she had! This was a momentous occasion for her and all her classmates. “Oh, we were all so excited. I can remember we all went backstage and they read out our names. I remember that little bit. Everyone was so excited, as though we’d been at the pub for about three hours, all rushing around. No, that was very exciting.”

Being a woman in medicine: perceived as blue stockings

Female medical students got to know each other well across year levels, as they had a common room. There was a sense of camaraderie amongst them since they were so outnumbered by all the men. The women were treated well by the men in their class, but since they were successful academic women, they were seen negatively as “blue stockings”1. Judy had been completely oblivious to the social hierarchy at the university until her boyfriend made her aware of it. Male medical students were at the top (“they were the ones you wanted to go out with”) and the female medical students were at the bottom. “That was my boyfriend; he told me that. He sat me down and told me. He was taking such a – not a risk, but his friends were having him on for going out with a medical student. I just opened my mouth and looked at him. I thought, this is a joke. I didn’t know. I had no idea. I don’t think I’m very sensitive to that sort of thing.” Her boyfriend also told her that she and her friend Sally should not join the rowing group because they would develop great big shoulders.

After medical school: finally able to go overseas

Judy spent two years (1961 and 1962) as a house surgeon at Waikato Hospital. The main pulls of Waikato were that it had a good social scene and that the hospital was good. Before she went there, Judy had already spent one summer in Waikato. The trainee doctors stayed at Lindisfarne, the accommodation provided for them by the hospital. Three women were staying in the hostel, including Alison Sommerville (nee Knox). The men stayed in a separate part of the hostel and there were houses provided for married couples (although very few of them were married at that time). The registrars stayed there too, and Judy remembers that they used to sit in a big lounge and talk about their cases. They were paid at this stage, so they had more money to spend on parties; drinking alcohol and smoking! Hamilton was easier going and less competitive than Auckland had been.

After these two years, Judy was finally able to travel overseas. It was common for medical students to go to the United Kingdom. Judy, who went to London, was no exception. Her primary motivation was her desire to travel, rather than to do further study. “I don’t think I was thinking about my career too much. Well, you want a break, don’t you? It’s an awful long time; eight years sort of studying.” Judy travelled to London as a ship surgeon on a cargo boat. The trip took two months. Though she was paid a nominal fee of only about $1, she was happy with the opportunity. On the boat, she had two clinics each day, but she did not have to do much. She remembers that the steward on the ship knew how to operate for appendicitis. “He was dying for someone to have appendicitis; we were going to do it on the operating table. Just as well we didn’t.” By this stage, most of her friends had returned to New Zealand and were starting families. She did have one friend in London, whose flat she moved into. Glenys Arthur (nee Smart) was also in London while Judy was there, but she was not pursuing the same specialty as Judy.

Originally, Judy had not had any plan to specialise, but when she got overseas, the opportunity was available to her. She was inspired to go into anaesthetics because there had been a very good anaesthetist at Waikato whom everyone had liked and who had loved his job. It was easy for Judy to find locum anaesthetic jobs which did not require too much of her. She does not think that she would have had the opportunity to specialise if she had stayed in New Zealand, as the hospitals in the UK were much bigger and the doctors there had far more experience.

This locum work which Judy did counted towards her specialisation in anaesthetics. The hospitals in the UK offered a 2-month course at the Royal College of Surgeons before she sat the exams. In order to specialise in anaesthetics, there were two types of exam which the trainee doctors had to sit. First, there was the Primary exam, which tested their basic medical knowledge including anatomy and physiology. Judy had to learn anatomy all over again for these exams. There were also specialist anaesthetic exams. Judy stayed overseas for about five years. She went to Sweden before returning to New Zealand. This was arranged by one of her tutors who knew the anaesthetist in Sweden. Judy found Sweden’s system very good as the nurses were more involved.

After five years overseas, Judy returned to New Zealand, where she met her husband-to-be, Garth Barfoot, who worked in his family real-estate business, Barfoot & Thompson. She finished her specialist training during her year at Middlemore. After this, she worked full-time at Auckland Hospital until she had children. After she had her first child, she worked part-time, as they could not get a full time nanny in those days, though there was a lady up the road who looked after the children when she was not at home. At the time, they did not offer paid maternity leave, so Judy used her sick leave when she had the first of her three children and she worked through her other pregnancies. She found that being an anaesthetist leant itself reasonably well to part-time work. Quite a few women went into anaesthetics for this reason. Judy was not the only one in her department working part-time, as some of the men also worked at private practices. She does not think that the hospital liked part-timers as much because they did not get as involved. They never said this outright, but the part-timers were less likely to get the big jobs.

Judy was never fond of teaching large groups of people, but she did do one-on-one teaching to the house surgeons in anaesthetics, which she enjoyed. Unsurprisingly, there has been a big change in technology over the years since Judy first embarked on her medical career. When she started in her role as an anaesthetist, they only monitored patients by using an ECG and feeling their pulse, but the technology is much more advanced nowadays. When Judy practised, she anaesthetised all types of people, but since then, sub-specialties have come in.

Advice to women embarking on a medical career: challenging, interesting and always changing

Judy would make sure that women beginning their medical degree are aware of how long the training takes. She is sure that medical school has changed a lot since she went through. It will now be far more interesting and will involve a lot more clinical work. In Judy’s opinion, being a doctor is a good job once you are doing it. There are lots of different avenues that one can go down with a medical degree, including going into lecturing. “It’s challenging, and it’s interesting, and it’s always changing. No, it would be good if you like that sort of thing.”

1: This was a historical derogatory term for academic women, implying that they were unfeminine and less fit to marry.