This biography is based on an interview with Rosalie Sneyd in 2017 for the Early Medical Women of New Zealand Project. The interviewer was Claire Gooder. Photos and additional information have been taken from “Rich Man, Poor Man, Beggarman, Thief” by James Sneyd.

Contents [hide]

Rosalie McPherson was born in Blenheim on the 14th of December, 1935. Growing up, she lived with her parents (Robert McPherson and Freda Neal) and her older sister (Valerie). Her early years were shadowed by the Great Depression and the Second World War. “Depression theoretically over, but you still felt it. You hardly got over the Depression when of course war came.”

Both Rosalie’s parents were teachers; her father taught metalwork and her mother taught home science. Her father had originally been a pattern-maker in the woodworking business, but he became a teacher during the Depression as the position had better job security (although he did not particularly enjoy the teaching work). He was fortunate not to lose his job in the Depression, but he did experience a pay cut. Having lost part of three fingers in his left hand at a young age while working in his father’s workshop, he was not sent to war. He was, however, in the Home Guard. Rosalie’s mother was very driven, being the first person in her family to go to university and choosing to return to teaching after having children, even though this was uncommon at the time. Both of Rosalie’s parents valued education deeply.

“He always said, ‘I’m not going to get you life insurance, but I will educate you – something no-one can ever take away’.” – Rosalie speaking about her father.

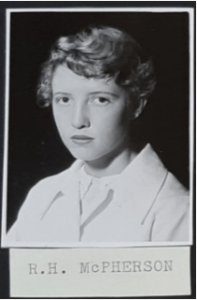

Rosalie was a hard-working student who spent most of her secondary school years at Marlborough College. This was a co-educational school where she was able to study all the subjects she needed in order to pursue a medical career. In 1963, after Rosalie had left, the school divided into two single-sex schools. The school on the original site became Marlborough Boys’ College, while Marlborough Girls’ College was established at a different site. Near the end of Rosalie’s schooling, her parents travelled overseas for six months, leaving Rosalie to live with her grandmother for that time. Her family moved to Taumarunui when her parents returned to New Zealand, as this was where they were able to get jobs. New Plymouth Girls’ High School was the closest school to their new home, so Rosalie – with all her belongings packed in an apple box – moved to the boarding school for her final year. She had not been to a boarding school before, so she struggled to adjust to the rules and regulations. The older students were expected to look after the younger girls. This was a time-consuming system that Rosalie was not used to, and she struggled to find the time to study. By this stage, Rosalie knew that she wanted to study medicine, so she chose subjects that would help her achieve this goal. There were only four students who wanted to study physics in her year, but the school brought in a retired “absolutely charming, lovely” woman to teach them.

Although there were no medical role models in her family, from the age of 15 Rosalie knew that she wanted to pursue a career in medicine after she sat her School Certificate (the equivalent of Year 11 in the current school system). She had been intrigued by medicine while growing up, as her mother had frequently been unwell. She also knew that her parents had been disappointed when her older sister had abandoned her dream of studying medicine a few years earlier (as she had found the initial year of Medical Intermediate too daunting) and would be pleased if she studied medicine in her sister’s stead. These, along with a determination to prove that girls could become doctors (after she had been told that it would be too hard for a girl) pushed Rosalie towards studying medicine.

Medical school: little time and little money

Rosalie enjoyed university life. Although there were no fees, the bursary she received (which gave her a small sum of money each week) was greatly appreciated. Her parents – who were “sort of floating at that stage” – were able to secure teaching jobs in Dunedin at Macandrew Intermediate School, so they moved south with her, allowing Rosalie to live at home with them while she studied. Although this meant that she did not have the typical student experience of living at a Hall of Residence, she was grateful that she did not have to pay for accommodation. Living at home did, however, make it harder for her to meet other students. The pathway into medicine involved achieving high enough grades in Medical Intermediate, a set course that included physics, chemistry, and zoology. Rosalie was very determined to get into medicine so she worked hard in her first year to ensure that she was successful. And she was.

“Well, I can still remember going down – they used to post the results in the archway, and being short, I’m looking – oh god, to see where the cut-off point was, and I was well in.”

There were about 120 students studying medicine in Rosalie’s year, but only around a dozen of them were women. The numbers changed slightly as some students repeated years or took a year out. Studying took up most of Rosalie’s life for her university years. She spent her days attending lectures and clinics and would continue to study at home after dinner. Rosalie was not sure what direction she wanted to take after she graduated, but she was focused on simply getting through her studies. She passed all her exams without ever needing to sit specials or repeat a year, although many of her classmates struggled with the final exam and were not able to graduate with the rest of their year group.

“Life was your medical course. Medicine isn’t difficult, but it is the volume of it. You worked all the time, and you had no money.”

Rosalie did not have much money as a student. She wore the same clothes to lectures every day because they were all she had, and most of her clothes were cast-offs from her sister. She supplemented her income by working during her summer breaks as a waitress or as a wards-maid. Her father, who felt that these positions were not good enough for her, did not approve of her working in these roles. Despite this, she enjoyed the jobs, as she felt that she learned from them and she appreciated the money which she earned. She also worked at the psychiatric hospital at Seacliff during the weekends.

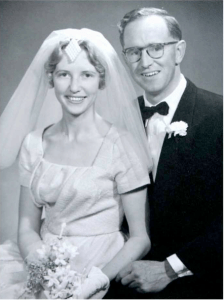

The sheer volume of study meant that the medical students had little time and little money, making it hard for them to socialise outside of class. Despite this, Rosalie made some friends through medicine – including Glenys Arthur (nee Smart) who later worked as a neurologist in Wellington, Janice McConville (nee McKay) who became a specialist paediatrician, and Viola Palmer (nee Heine), who was a general practitioner – and they still managed to do some activities together outside of studying. All these friendships lasted right through life. The medical school was separate from the rest of the university, meaning that she did not have friends outside of her course. Rosalie met her future-husband Sam at the beginning of her fourth year. He was also a medical student, which meant that he understood the pressure that Rosalie was under. Sam had originally been a year ahead of Rosalie in medicine, but he took a year out to complete a Bachelor of Medical Science, which meant that he joined Rosalie’s year group in their fourth year. Although they did not have a lot of time or money to spend together, they had a coffee together every week and occasionally went out to see a movie. In their sixth and final year of study, Rosalie chose to stay in Dunedin (for financial reasons), while Sam travelled to Auckland (his home town) for the year, also for financial reasons. They both graduated in 1959, within a week of sitting their final examination.

After graduation: balancing work and children

Rosalie and Sam were married the week after they graduated (on Rosalie’s 24th birthday). They kept the wedding simple and were married in a church. A lot of Rosalie’s classmates also got married around this time, and they attended each other’s weddings. The next year (1960) was the registration year for both Rosalie and Sam. The couple moved to Auckland for this, where they originally lived in Mt Wellington, then moved to Greenlane (an ideal location for getting to the hospital). Nobody had any difficulty getting a house surgeon position in those days. She became pregnant during this year and she suffered from morning sickness, resulting in her only working until September before having her first daughter. The following year, when their baby (Mary Jane) was about 4 or 5 months old, the young family moved back down to Dunedin. Rosalie began working again when Mary Jane was 6 months old. She worked in Accident and Emergency (A&E) to complete the final three months of her registration year. Others around her disapproved of the fact that she was going back to work full-time with a young baby, but Rosalie’s mother was able to look after Mary Jane, and she was able to have some flexibility in her work.

After Rosalie finished working in A&E and was registered, she moved on to doing locum work in general practice. This meant that she had sporadic episodes of full-time work when a GP needed someone to cover them. The family spent three years in Dunedin while Sam worked on his PhD in clinical biochemistry. While they were there, they lived in three different areas of Dunedin: St Clair, Caversham, and Easther Crescent. They also had their second child (James) during this period of their lives.

“Locums are hard work … Everyone coming through the door is new.”

After the time spent in Dunedin, Rosalie and her family travelled by boat to Nashville, Tennessee, where Sam had a position at Vanderbilt University doing post-graduate clinical biochemistry work. It was a shock to be living in a country with such a different culture. Since Rosalie did not have her American boards, she was unable to work with patients while they were in the United States. Instead, she got a job doing cytology work in the pathology department, as this did not involve patient interaction. Although she had not done this work before, she was able to learn on the job. By the time she left three years later, she was running the cytology lab. The couple had their third child, Catherine, while they were overseas, and Rosalie continued to work throughout her pregnancy and soon after giving birth. Even though they were in a foreign country, there was a good social group that Rosalie and Sam were able to connect with through Sam’s work.

At the end of 1967, the family returned to Dunedin, where Sam had a position as the Chair of Clinical Biochemistry. Rosalie was able to use her newly acquired cytology skills to work in the pathology department at the Dunedin Medical School. In 1974, the family took a sabbatical to Cardiff, Wales. Upon returning, Rosalie worked part-time at Student Health in Dunedin. In this position, she was able to have interactions with patients, which was an aspect of medicine that she had missed in the cytology work. In 1980, the family returned to Nashville on another sabbatical. When Rosalie returned from this, she began working as a Public Health Doctor. As part of this job, Rosalie did school inspections, but she did not find this work particularly engaging: “What the job was, I never discovered.” She was able to work half-days and have someone look after her children in the morning while she worked. Rosalie gave birth to their fourth and fifth children (Elizabeth and John, respectively) around this time.

After she had spent a few years working in public health, Rosalie moved on to work in hospital administration. This was a busy time for administrative workers because there was a push for shorter hours for house surgeons. This meant that the administration team needed to find more house surgeons, having to recruit them from overseas. Although Rosalie thought it was important for house surgeons to work more reasonable hours, she was concerned that there would be less continuity of patient care. Her medical background was essential for this work as she knew what the house surgeons were facing so knew how she could help them. Rosalie became very interested in information systems as she felt that decisions were often made without considering all the available information. However, she did also miss clinical work.

“I did become increasingly interested in the bird’s eye view of medicine, and information systems … I waged war on forms. Every form had to have a purpose and go to the right person.”

In 1989, medical people were removed from positions of medical administration, and Rosalie was made redundant from her position as Acting Medical Superintendent.

In 1990, since Rosalie had lost her job and her husband had resigned from his, they decided to move to Fiji, where they spent three years. Their youngest child (who was 17 at the time) stayed in New Zealand to go to university. Sam had a job in Fiji to help re-vamp the medical school there. The couple had been told that there would also be a job organised for Rosalie, but when they arrived they discovered that there was not. Rosalie created her own position and spent the time in Fiji looking at the Fijian medical reporting system. Then she worked for the World Health Organisation on non-communicable disease in the region. She and her family also travelled lots while they were there, which she enjoyed.

After this, they spent a year in Hong Kong, as Sam had a position helping to revamp the clinical biochemistry part of the medical course. This was their first experience of living in a big city. Rosalie appreciated the year they spent there, but would not have wanted to live there long-term. She did some work doing routine medical examinations in a refugee camp, but she spent most of the time simply exploring: “I had a ball.”

They returned to New Zealand for a few months, then travelled to Kuching, Sarawak, in Malaysia. Once again, her husband was helping to build up the Clinical Biochemistry Department. There had already been contact between Dunedin and Kuching, and others from Dunedin had travelled there before them. They spent the year and a few months over there, and Rosalie relished the opportunity to explore a new area of the world.

Rosalie’s children

Throughout her life, Rosalie’s family has been, and continues to be, very important to her. She and Sam had five children. Their eldest, Mary Jane, studied medicine and went on to do epidemiology. Their next child, James, studied mathematics. He got his PhD in mathematics in New York. Catherine did a PhD in English and her first husband was in the medical field. Elizabeth also has a PhD in mathematics. John, the youngest, studied law.

Rosalie’s perspective of being a woman in the medical profession: “There was never a suggestion that I shouldn’t be there.”

Rosalie was one of a dozen female students in her year of 120 students. She did not experience any discrimination based on the fact that she was a woman. However, she did occasionally feel as though some of her teachers thought that men would be more successful in their medical careers than women would be. Thankfully, this was a rare occurrence. Once she was in the workforce, it was reasonably common for Rosalie to be mistaken for a nurse, and patients were often slightly surprised when they found out that they had a female doctor.

“I didn’t feel any discrimination. I really didn’t, although just occasionally there would be some remark from our teachers, throwing doubt on how much we were going to contribute to the profession.”

Rosalie does not regret choosing the medical profession. She does wish that she had spent more time doing clinical medicine and that she had specialised, but if she had done that, she recognises that she would have had less time to spend with her children. This is not something she would have wanted, as she “hated leaving them in the mornings”. Rosalie enjoyed the medical career that she pursued, and was encouraging of her daughter who chose to go into the same field.

“ I was never sorry I did it … because I enjoyed it.”

Bibliography:

Rosalie Sneyd interview transcript

Sneyd, J. (2009). Rich Man, Poor Man, Beggarman, Thief: The ancestry of my parents.