This biography is based on secondary research for the Early Medical Women of New Zealand Project. All sources can be found in the bibliography at the end of the biography.

1897 GRADUATE

Contents [hide]

High Responsibility from a Young Age

Twins Christina and Margaret Barnett Cruickshank were born on 1 January 1873 in Palmerston, Otago [1] [2] [3] [4] [5] [6]. They were the eldest of seven children to George Cruickshank and Margaret Taggart [7]. Both George and Margaret had migrated from Scotland to New Zealand. George was originally a farmer from Aberdeen. When farming took a downturn in the 1850s, he left the United Kingdom with high hopes of finding better luck in the “promising colonies” of Australia and New Zealand. He landed in Australia where he worked as a stonemason in the gold mines. By 1863 he had not made any significant money and so he moved to Dunedin with his friend Mr Ledingham, where he took a job as a contracting roading engineer [8]. Margaret originated from Inverurie, a small town near Aberdeen. David R. Lockyer believes that George and Margert knew each other before arriving in New Zealand and that they had been sending letters to each other for eight or nine years before she emigrated from Scotland [8]. Upon reconnecting in New Zealand, the couple became engaged and married on 27 February 1872 at Knox Church on George Street [9].

Though the twins’ place of birth is registered as Palmerston, the family were living on a 90-acre farm named Riverheads in Hawkesbury (later in the Waikouiti region) [7] [8] [9]. By the time of the seventh child’s birth, their mother had become quite sick. Christina and Margaret took over her position as homemaker bycaring for the younger children and looking after the house. Tragically, their mother passed away on 19 June 1883 of puerperal fever [7] [8].

Top of their Class the Whole Way Through

With the death of their mother, Margaret and Christina assumed her full role looking after their younger siblings and looking after the house. From ten years of age, the twins decided to alternate attending school so that one was always home to help the family while the other was learning [3]. The twin that went to school would come home and teach the other in the evening. They would alternate who attended school and who looked after the house every six months [1] [8] [9]. This plan ensured that they were not missing out despite their extenuating circumstances at home. An article written about their time at the state primary school state that they were ahead of their peers [2].

Following this, the twins moved to the boarding school at Palmerston District High School. David Lockyer argues that they didn’t find boarding school challenging considering what they had come from [8]. Each holiday break they travelled back home to the farm. They both achieved academically well and received an Education Board Scholarship to Otago Girls’ High School in Dunedin [4] [5] [7] [8]. This scholarship paid for their fees and their father paid for their board. In 1891, Christina and Margaret were awarded joint dux at Otago Girls’ – with only one point difference between them – and a University Junior Scholarship to Otago University [3] [5] [6] [7] [8]. While Christina followed the path of education, Margaret was unsure what course to enrol in.

Deciding to Enrol in Medical School

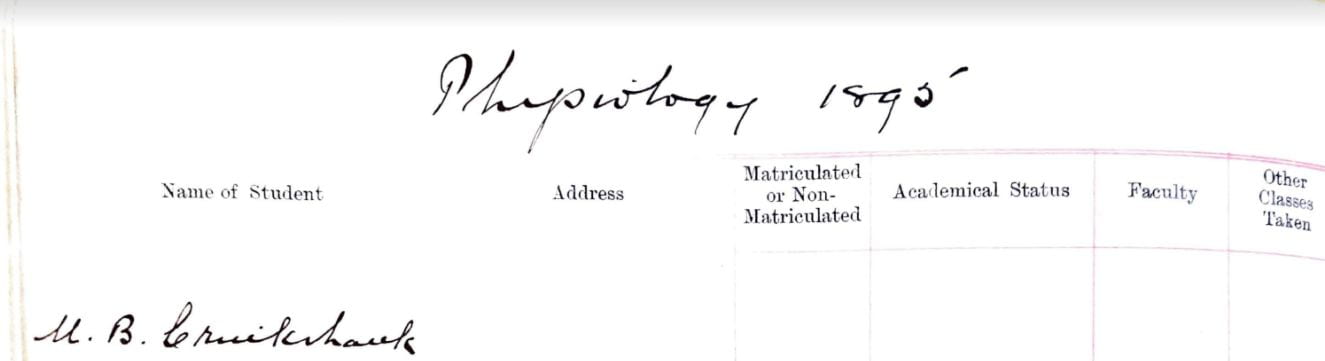

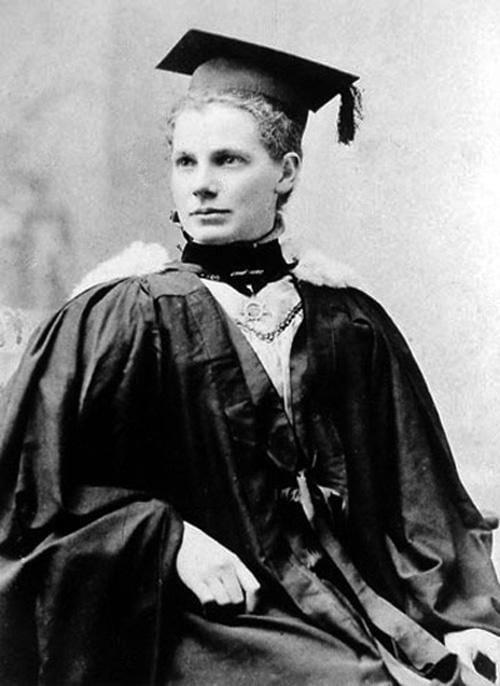

While attempting to make her decision, Margaret approached a trusted teacher who had become a motherly figure to her, who encouraged her to follow the path of her friend – Emily Siedeberg who had enrolled in the medical course at Otago University. When this was first suggested to her, she responded straight away with “Oh no, I could not!” However, a short while later she ended up enrolling in the program after having spoken with Emily [3] [6] [5] [7] [8]. In 1892, Margaret became the second woman to enrol in New Zealand’s only medical program [7] [10]. When in Dunedin, Margaret and Christina rented a place together [8]. Margaret enjoyed her course, graduating with an MBChB in 1896 without failing any papers. Notably, this was the same year that Ethel Benjamin graduated from the University of Otago and qualified as the first woman lawyer in New Zealand [3].

Margaret was not long out of the university, however, as she returned to study not long after obtaining her first medical position. In 1903, she obtained her degree of Doctor of Medicine (MD) from the University of Otago – the first of three postgraduate qualifications she would obtain throughout her career [6] [7].

Moving to Waimate and Making a Name for Women Doctors

Following her graduation ceremony in 1897, she entered the job market. A teacher from Otago Girls’ High School was an acquaintance of a doctor in Waimate who was looking for an assistant. This teacher recommended Margaret for the job and so she travelled to Waimate for the interview. Margaret was offered the job on the spot and accepted it straight away – officially becoming the first New Zealand woman doctor to register (03 May 1897) and subsequently practice [6] [8].

The head of the private practice was Dr H. C. Barclay, and Margaret boarded with him and his wife when she first moved to Waimate [8]. Her first record at the practice is on 03 March 1897, where she acting as the anaesthetist for a surgery Dr Barclay was performing. She continued in this position until 20 March 1898 where she performed her first surgery as the operator while Dr Barclay administered the anaesthetics. By 1908 she was performing the majority of the surgeries at the clinic. Margaret spent the majority of her working time at Dr Barclay’s private practice, where she became a partner in 1900, however she also obtained a position at the school (specialising in midwifery and surgery) and then later at the public hospital [8].

Margaret was an incredibly hard worker and became known for her dedication and devotion to her patients – through which she gained their trust and affection [3] [7]. Indeed, Margaret did not experience any hostility from her male colleagues [2]. This attitude is corroborated by an editorial in the Waimate Times from 1897: “The day of the lady doctor, like the women’s franchise and the labour legislation, seems to be upon us … We cannot do less than wish this clever pioneer much happiness and success in the profession she has selected” [3]. Some of her success in Waimate has been attributed to her knowledge of the difficulties of rural life. Margaret was happy to walk the many miles between clients and while at their homes often helped with the housework. She adopted the attitude of only requiring her patients to pay for her services if they were able to [8].

As New Zealand’s first woman doctor to register and practice, “it was inevitable that reporters would come knocking on her door” [2]. Margaret disliked publicity, however [4]. For example, in 1900, she was approached by Kate Sheppard, a New Zealand suffragist and writer, who sought to write a piece on Margaret for the White Ribbon – a paper that was organised by the Women’s Christian Temperance Union. Margaret declined the interview, stating that she “she disliked the essentially egotistical character of an interview: ‘Though I may have had a little measure of what the world calls success, I am on a very lowly rung of the ladder yet, and from such have a very circumscribed outlook so that I feel myself hardly fitted to speak very dogmatically about questions affecting women practitioners” [6]. Instead, Margaret agreed to meet Kate Sheppard for an informal conversation [8]. They spent a few hours together, “hours that were bright and full of interest”. Kate wrote that Margaret had been very kind [6] and she greatly appreciated the position she was in: “Both in my student and professional life, I have met with nothing but kindness, courtesy and help from my teachers and brother practitioners, and I hope that I may never give them cause to treat me otherwise” [9].

Educating the Public & Hospital Politics

Margaret was a firm believer of educating the public on both medical and other issues. After a railway accident in Waimate, the town established a St John’s Ambulance and Medical Course and Margaret was elected as the lecturer for first aid classes. These lectures sought to teach the following items:

- Encouraging people spiritually and morally

- Humanitarian and charity work

- Aiding the sick, wounded, disabled, and suffering

- Awarding medals, badges or certificates for special services

- Maintain and develop the St Johns Ambulance

- Distribute textbooks and other training materials

- Instruct on First Aid and Nursing [8]

The community responded positively to these courses and Margaret’s colleagues at the hospital advised her that they were thankful for the increasing education of the public about medical matters.

Margaret’s educational endeavours continued outside of directly working with patients. Between 1909 and 1912, woman doctor by the nom de plume “Margaret Faithful” wrote articles for the White Ribbon. Though it has never been proven, these articles are assumed to have been written by Dr Cruickshank. This is due to the content involved, but also because the articles stop appearing the year Margaret left Waimate for her year-long overseas holiday. The articles published covered a number of topics, such as the promotion of healthy living through nutritional information on certain foods and diets and the explanation of common illnesses – examples include bloodlessness due to ulcers in the stomach and medicine you should take for constipation [8].

After 14 years in Waimate, a committee of local doctors (including Margaret) was established to address a rising problem: hospitals were admitting more and more people with unaddressed concerns even though these patients claimed that they had seen their local General Practitioner (GP). In order to promote continuity of information and better communication between the hospital and the GPs, the committee conducted an inquiry into whether the GPs could become registered doctors at the hospital. This was also important as some GPs were not as familiar with current research, however, their patients did not wish to change to a new practice because they wanted to stay with the same person they had always seen and trusted.

When the structure of the registration of local doctors was being discussed, it was suggested that there would be a hierarchy – a hierarchy that would put Margaret at the bottom. Margaret put her foot down, stating that she was a well-qualified and experienced doctor and surgeon who had given anaesthetics for 14 years as a free service – an endeavour that had benefitted the public but had gained her little recognition. She refused to be placed at the bottom of the hierarchy, classed merely as an anaesthetist and not a doctor, alongside “a married lady who had got her home, children and husband to manage. I would like the Board to recollect that. I have a right to be put on the same footing as the other doctors in the town” [8].

Holiday & Postgraduate Studies

On 29 January 1913, Margaret advised the chairman that she would be taking a leave of absence for twelve months to the Old Country – England. As a farewell and as a testament to her devotion to the community, the town held a public function for her [8]. She was presented with 100 sovereigns and a gold chronometer watch and chain. Members of the public spoke about her “freedom from pretence, her capacity for loyal friendship, and her gentleness, patience and unselfishness” [4] [7].

Margaret left on a ship bound for London with her youngest sister Isabel. On the journey she wrote many letters to her friends and family. On route to England, the sisters visited Rome where they attended multiple social functions [8]. She also visited various places in America [6]. While she was enjoying her trip overseas and her break from sixteen long years of work, the people of Waimate were “sorely missing her” [8]. Dr Barclay was looking after the clinic by himself and was struggling to keep up with both of their patients in Margaret’s absence.

When she eventually landed in Scotland, Margaret enrolled herself in postgraduate courses in Edinburgh and then later in Dublin [4] [8]. She also travelled to London to visit the St John’s Association headquarters to learn about the courses they were running in England and how she might be able to adapt these for those attending the course in New Zealand [8].

Returning to work in New Zealand

Margaret returned to New Zealand on the 02 March 1914. She returned to the practice almost immediately. Upon hearing about Margaret’s upskilling and adventures, Dr Barclay decided to take an 18-month sabbatical for himself, with the hopes of also taking a holiday and further study [3] [8]. He left in May 1914, leaving Margaret to look after the clinic by herself [8]. She was also appointed the role of hospital superintendent and she was associated with the nursing fraternity, lecturing and examining nurses [2] [7]. On route to England, the First World War broke out and Dr Barclay wrote back to New Zealand advising that he would be joining the war effort through the Royal Army Medical Corp [4] [8]. This meant that Margaret was going to be looking after two loads of patients for the duration of the war as well as maintaining her volunteer work for the Red Cross [5] [9]. She conducted her local rounds by bicycle and travelled to those far away with a horse and gig [6].

In September 1914, Waimate held their first fundraiser for the war effort – a Harvest Festival. This was shortly followed by a local Patriotic Fundraising Campaign. Early in 1915, a North Island fundraiser was announced to raise money for the relief of the poor in war-torn Belgium and Britain [8]. It was to be a Queen Carnival and each town was expected to put forward a candidate. Margaret was elected as the candidate for Waimate and it became quite an affair [4] [7]. Votes were cast by members of the public through monetary donations. For the majority of the competition, Margaret was a leading contender. She was paraded through the town in a car with people anxious to see her. The final day of the carnival was held in Timaru and many travelled from Waimate to support Margaret. It was a very exciting day. Witnessed described her as “tall and gracious, in her beautiful court dress of satin and lace, her fair hair with its tints of gold, arranged in a coronal” [7].

Unfortunately, Margaret came in at second place to the Fairlie representative. However, £10,000 had been raised for the war effort. After the whirlwind of events, everything quickly returned to normal for Margaret. In fact, she announced that she felt bad because she had done nothing but enjoy herself throughout the whole process and it was good to be back at work [8].

For the rest of the war, Margaret continued on with her work, which included bringing about many changes to the hospital. In 1916, she advocated for better lighting and spoke strongly on the lack of accommodation for the nurses [8]. In 1918, the influenza pandemic reached New Zealand. A public meeting was held and Margaret reported that the situation was quickly getting out of control. She used Christchurch as an example to demonstrate the effects of not setting up adequate precautions early on. As a result of her speech, the council determined that hygiene standards at hotels needed to be raised and bars had to be closed to prevent spread. They also decided that only the most serious of cases were to be admitted to the hospital – minor cases were expected to self-isolate at home [8]. Margaret’s driver fell ill during the epidemic, so she ended up cycling to her patients, continuing to attend to as many people as possible [3] [5] [7]. She also continued to help her patients: “Where the mother was laid low, she fed the baby, prepared a meal, and in many cases where whole families were laid low she would milk the family cow to obtain milk for their sustenance” [2] [3] [6] [9].

Death & Legacy

The workload of looking after patients during the influenza epidemic quickly took a strain on Margaret [6]. She was already at a high risk of infection due to her interaction with her patients, however she also worked through most days and nights [3]. She eventually fell victim to influenza and pneumonia [6]. She attempted to remain at her post for a few more days however on 18 November she was admitted to the hospital. On 23 November, another doctor in Waimate, Dr Green, was admitted to the hospital alongside her. “She battled the disease tirelessly” however, on 28 November she passed away [1] [2] [7].

Due to the epidemic, Margaret did not want people congregating together and therefore the funeral was not advertised. However, her popularity was too great and during her funeral procession, the streets were lined with people honouring her memory [4] [8].

On 25 January 1922, five years after her death, the town erected a marble statue in her name [8] [9]. The residents of Waimate had commissioned the sculptor, William Trethewey, to design and craft the statue based on photographs. The statue was unveiled by Mrs Barclay in the town’s central park and still stands there today [2]. The inscription reads: Margaret B. Cruickshank M.D. The beloved physician, faithful unto death. This statue was the first erected to a woman in New Zealand [6].

In 1948, the Waimate hospital named their maternity ward after her: “Margaret Cruickshank Ward – Maternity” [5] [7] [8] [9]. In 2007, the Ministry of health named the pandemic preparedness exercise “Exercise Cruickshank” in honour of her work during the 1918 influenza pandemic [5] [9].

“We wish that, in years to be, the story should be told of a woman who was brave, and strong, and kind, and true as steel, who had a heart with room for others’ sorrows, and hands swift and sure in deeds of loving service; who gave her life as truly for duty’s sake as any soldier on the “gallant, glorious” field. She is dead, but her influence on others is a living thing that cannot die.” – E. Morrison, 1924.

“Yes, Margaret Cruickshank was a doctor; but she was also a spiritual woman of diverse abilities. A superficial glance revealed a somewhat austere, inflexible severity that reminded me of the greenstone (pounamu) boulders I had come to know on the West Coast. Further study revealed her warm, caring nature exhibiting compassion, gentleness, humour and attention to detail. As with polished jade, I found a rare beauty, a life that was engaging and noble.” – David Lockyer, 2014.

Bibliography

- Council, T.D. Dr Margaret Barnett Cruickshank. 2021 [cited 2021 March 19]; Available from: https://www.timaru.govt.nz/community/our-district/hall-of-fame/category-three/dr-margaret-cruickshank.

- Libraries, C.C.C. Dr Margaret Cruickshank. n.d. [cited 2021 March 19]; Available from: https://my.christchurchcitylibraries.com/dr-margaret-cruickshank/.

- Houlahan, M., Heroic Woman Doctor Succumbed to Flu, in Otago Daily Times. 2018: Otago.

- Morrison, E., Dr. Margaret Barnett Cruickshank, M.D: First Woman Doctor in New Zealand. 1924, Christchurch: Whitcombe and Tombs Limited.

- Heritage, M.f.C.a., Margaret Cruickshank. 2017: New Zealand History.

- Charlotte Macdonald, M.P., and Bridget R. Williams, The Book of New Zealand Women = Ko kui ma te kaupapa. 1991, Wellington: Bridget Williams Books.

- Hughes, B., Margaret Barnet Cruickshank, in Te Ara – The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. 1996.

- Lockyer, D.R., Beyond the Splendours of the Sunset: A Biography of Margaret Cruickshank, ed. D. Mackenzie. 2014: David R. Lockyer.

- Cooke, N., A Remarkable Woman. Margaret Barnet Cruickshank. The New Zealand Genealogist, 2020. 51(382): p. 60-63.

- Society, R., Margaret Cruickshank, in Royal Society – Te Aparangi. n.d.