This biography is based on an interview between Mareeta Dolling (Moana’s granddaughter) and Alwyn Dolling (Moana’s daughter) in March 2021 for the Early Medical Women of New Zealand Project. Further information and photographs were provided by the extended family.

1921 GRADUATE

Contents [hide]

Early Life: Encouraged To Pursue a Career

Moana Maru Anderson was born on 9 March 1897 to Crawford Anderson and Mary Anderson in Stirling, South Otago.[1] Crawford was a ‘farmer, pioneer, and politician’. He had driven a mob of cattle from the North Island to the South Island over the ferry before settling in Balclutha. In Balclutha, he met and married Mary (nee Hamilton).

Moana first attended Stirling Primary School, followed by Balclutha District High School, where she earned a University national scholarship to Otago Girls’ High School due to her good grades.[2] In 1915, she achieved dux and a prize that came with a medal.[3]

Moana had the impression that her and her siblings were always expected to have some sort of vocation, especially the girls. Moana was very bright and her parents encouraged her to follow any career of her choice, for which she chose medicine: “There was no pressure but just some sort of expectation that the girls should be educated in their lives”.[4] All of the children ended up in successful careers: Her sisters Renata and Reinga (Nettle) Airini and Meri became teachers and her brother Hone was a dairy farmer. Her other brother, Ngaire, tragically died at Gallipoli.

Medical School, Southland Hospital & Meeting Peter Gow

Moana entered Otago University in 1916, where she was enrolled in the medical program. Though the University had a colourful social scene, she did not participate too greatly in it. She tried smoking and alcohol but did not like it. Unlike many of her peers, Moana did not enter a hostel or go flatting. Rather, she boarded at the Presbyterian minister’s house, which was located beside Knox Church at London Street. She got on well with the family. “They were Welsh and this is where Mum heard the girl’s name “Alwyn”. Mum liked the way the mother called it out and the way it sounded so that is how I (Alwyn) was named”.[5]

One of Moana’s placements was during the 1918 influenza epidemic. She told her children about one time when she was in an isolated valley: “she went to a farm and found both parents had died of the influenza and she had to ride to the next farm to get temporary care for the orphaned children”.[6] Moana achieved well at Otago Medical School and did not have to repeat any papers. She graduated with her MBChB in 1921 with five other women.

Following her graduation, Moana was offered a house-surgeon position at Southland Hospital, Invercargill, which she held for two years.[7] It was during this time that she met the Roger family, who were to become very important life-long friends to her. She spent a lot of time with Jenny Roger, who later became a well-known artist.[8]

While in Invercargill, she met Dr Peter Gow, a doctor from Winton who was bringing some patients who required the services of a better-equipped hospital than what was available to them in their local area. Peter was a widower (his late wife had passed away in 1917) with three children, Brent, Bobs (Robert), and Jack. Elinor Washington (nee Gow) believes that when Peter was told a woman trainee doctor was coming to work with him, he wrote to a friend in South Africa that “he found it hard to believe a young woman was coming to work with him”. However, when 45 year old Peter and 25 year old Moana met, they quickly became friends and then fell in love. They were married on 5 January 1923 in the Church of England in Stirling. Moana moved to Winton to be with him and his family. They had a further four children: Ngaire, Alwyn, Elizabeth, and Neil.

Moana named her firstborn son Ngaire after her brother who had been killed at Gallipoli. Tragically, he too passed away on 20 October 1929. Alwyn recalled: “I remember telling mum that Ngaire would not talk to me when he was in his cot. I knew something was wrong. He had pleurisy and pneumonia and died of that. There were no drugs or medication to treat it in those days and I think that a lot of children and people died of that in those days. It was such cold conditions too … I saw mum and dad crying together in each other arms upstairs in the bedroom.”. [9]

Alwyn felt that all of the children “had a close relationship with our parents and home, and we were exposed to a lot of what they did in our community. I never felt any difference between us as children even though we had different mothers. We all loved each other. Mother (Moana) bought them all up as her own”.[10]

Establishing a Practice in Winton

In 1924, shortly after moving to Winton, Peter and Moana established their own general practice at their home in Park Street.[11] The house was a large two storey building with two entrances – one for the house and one for the practice. “The surgery always had an open door to the rest of the house so that mum or dad could walk through to our part of the house. I remember going into the waiting room often and talking to the patients waiting”.[12] The practice had about two rooms (one for Peter and one for Moana) and a waiting room. They never performed surgeries at the practice, as all serious cases went to Invercargill Hospital. There was a local hospital though, which was mainly for women and babies. Sometimes Moana would see her patients at the hospital. On Sunday afternoons she would do her rounds at the hospital, bringing along her children: “we were allowed to hand around the tea trays for the patients and that was really special thing to do as others never got the opportunity to do such things”. Tommie Walker was the local chemist, with whom Peter and Moana frequently worked.

Both Peter and Moana worked full-time so they had a maid to help with the housework. Alwyn recalled having a longtime, live-in maid called Anne who did most of the cooking, laundry, and cleaning. Moana enjoyed cooking, but because she was so busy, she did not do it too often. They also had a gardener to keep up with the large garden. Alwyn mentioned that the gardener was often one of her parent’s patients. “The gardener had to work along with mother’s instructions – she had a strong interest in the garden”. As the house was on a lot of land, they also had chickens and a stable with ponies. They had a sulky (a light two-wheeled horse-drawn vehicle for one person) that Peter used to do house calls. As soon as cars were introduced, both Peter and Moana had one. Alwyn remembered that her father had a Ford 2-seater with a driver and then a Buick, which he drove. They also had Austins at one point.

Peter and Moana worked whenever people needed treatment. Peter did the majority of the house calls, driving into the country and isolated areas at all hours to attend to those in need. Alwyn mentioned that this was quite demanding and he would tire quickly. When their children were at an age where they could drive, they would drive their parents around to help out. Occasionally on house calls, he would stay with is patients and watch the horse races so that he could have a short break. Their parents got on well with anyone and everyone. They also often did voluntary calls, where possible their patients paid in kind: “a leg of lamb from the farmers”. In fact, they became famous for their generosity, particularly as they “gave free medical care to patients who were struggling financially” during the Depression years.[13]

The pair ran their general practice together for 20 years. Tragically, Peter passed away in 1943, aged 65. Moana continued to run the practice until 1946 when she made the decision to move back to Dunedin.[14] Running the large Winton practice alone was quite a feat for Moana. The practice seemed to cover half of Southland and during the Depression and War years (1930-40s), money was tight in the farming communities of Southland – she would often take a gift in lieu as payment. Her daughters, Alwyn and Elizabeth, were at boarding school during this time, but her youngest child Neil was only six. Kate Gow recounted: “When she had a call out at night, she had a bed made up in the back of the car for Neil and the family fox terrier dog Nip, and off they would go. If Dr Moana got tired, she would just pull over to the side of the shingle road and have a catnap. Over the years, many local Southlanders have told of checking up on her, Neil and Nip! She managed this way till Neil turned eight when he was sent to boarding school in Dunedin, and Moana finally sold the practice to two male Doctors returning from the war. I think this was in 1947.”

Practising in Dunedin and Cherry Farm

The first edition in May 1946 of the Otago Daily Times published an article announcing that Moana was commencing practice at 26 London Street “in rooms previously occupied by the late Dr William Newlands”.[15] Dr Newlands had been a friend of Peter Gow. Moana and all of her children moved into the large house. It was halfway up a steep hill and had two storeys at the front and three storeys at the back of the house. The practice had a separate entrance to the rest of the house and was on the ground floor. Behind the practice was a self-contained flat where Mrs Newland lived until she passed away. Moana’s family occupied the top half of the house up a “beautiful big staircase”.

Moana moved into her own house at 11 London Street in the late 1940s, which also had purpose built consulting and waiting rooms. A feature of this house was the large stained glass window illuminating the staircase. This house overlooked Knox Church and the house where Moana had boarded as a student during her time at Otago Medical School. In later days, Moana shared this practice with Dr Kathleen Rose Standage, who was a 1953 graduate from the Otago Medical School.

Occasionally Moana would take a break and get a final year medical student from Otago University in to do a locum to cover for her.[16] She bought a crib at Karitane to use as a weekender. It was only a short drive from Dunedin, so it was easy for her to go there when she wanted a break from Dunedin.

Moana worked in this practice until 1962 when she retired. She sold the practice but held onto the house. Following this retirement, she travelled to the UK and Europe. She worked her passage there as the ship’s doctor. This trip included visiting many places associated with the Anderson and Gow families. She brought back a red Morris 1100 car from the UK that became a well-known sight driving around the Karitane district. However, Moana was restless following her retirement and took up a position at Cherry Farm Hospital as the medical officer from 1965 to 1972.[17] Cherry Farm was a live-in working farm for men with mental health issues or intellectual disabilities. While working here, she lived at her crib in Karitane.[18]

Bridget Allan remembers when her family stayed with Moana in Karitane, the radio was often on so she could listen to the cricket. “While the garden to the east of the house was for vegetables and flowers (especially roses) she kept the west garden as grass so our family could play cricket out there – which we did for hours on sunny days.” There were also many days when the grandkids took out the two dinghies and rowed across the Waikouaiti River estuary to explore the sand dunes on the other side. She remembered that Moana hosted many family gatherings at Karitane so that all of the cousins (Gow, Dolling, and Allan) had time to connect with each other.

Fighting for Women’s Rights

Alwyn mentioned that her mother “was always pushing for women’s betterment in the community”. She believed that more women should take up medicine, or at least get a good education so that they had the opportunity to take control of their lives. “She was always involved in women’s leadership in some way and on committees all through her life, for this reason”.[19]

She was a prominent member in the National Council of Women, the Federation of University Women, the New Zealand and the International Medical Womens’ Associations, and the Girl Guide movement. In 1955, she was elected as the president of the New Zealand Medical Womens’ Association.[20] After 50 years’ membership, she was granted a jubilee membership. In the same year she was elected the Dominion President of the Pan Pacific Womens’ Association, which she held for six years. During these six years, she attended two international conferences. The first was in 1955 in Manila where she presented a paper entitled “Social Security for Women in New Zealand”. Then in 1958, she led the New Zealand delegation to the association’s international conference in Tokyo.[21] In 1969 she was awarded a life membership due to her service.

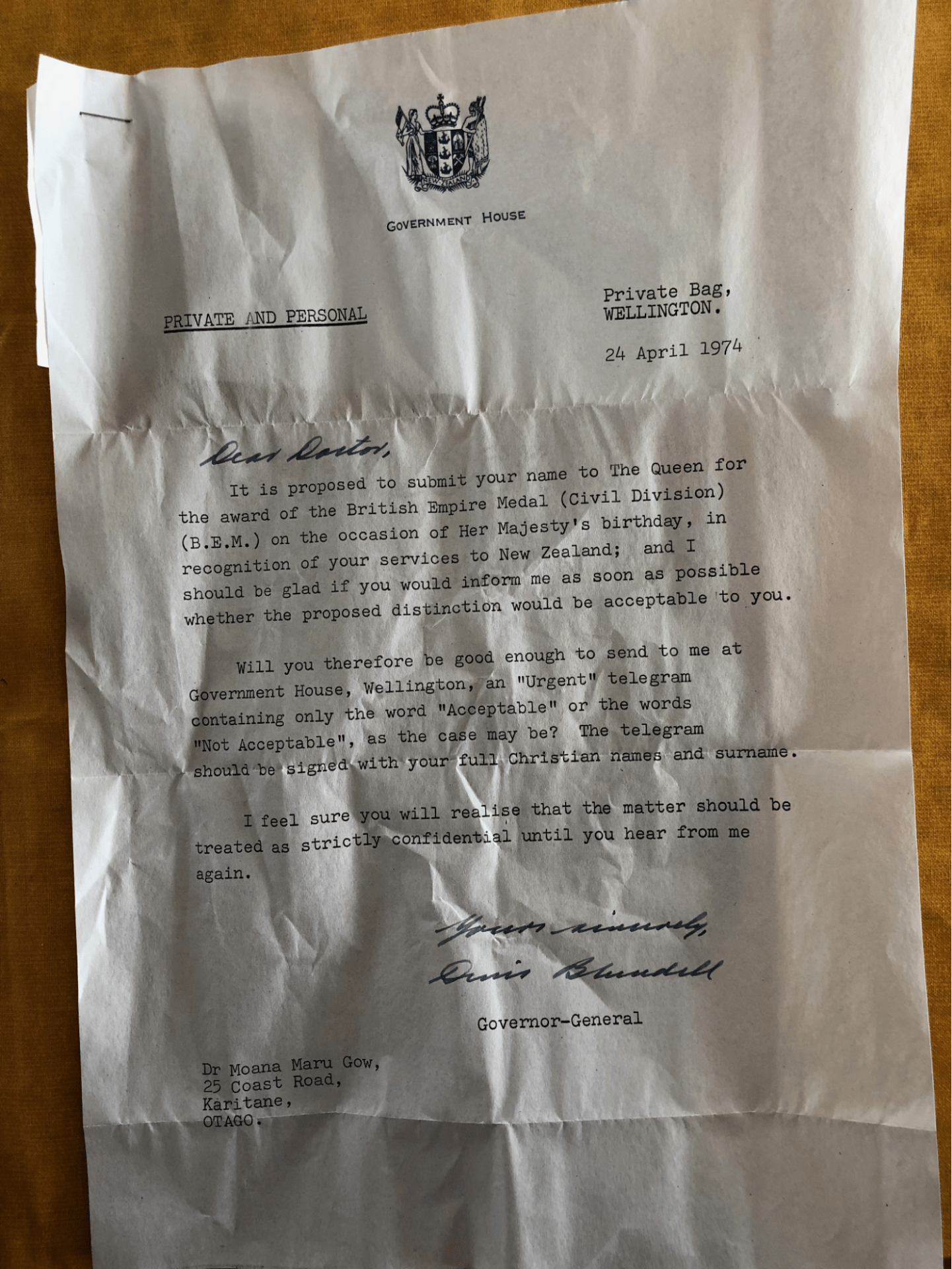

In 1974, she was awarded the British Empire Medal in that year’s Queen’s Birthday Honours.[22]

Interests Outside of Medicine, Death & Legacy

Moana had many interests outside of medicine, one being gardening, particularly alpine gardening and botany. She also had interests in horse-riding, ornithology, cricket, and occasionally tennis and basketball. She was a consistent attendant of the Anglican Church. She first took up painting while living at Winton after meeting a self-taught painter who inspired her. “She used to take a canvas stool and drive to a spot and do a rough painting of the landscape or whatever took her eye, and then finish it later”.[23] She was a regular exhibitor with the Otago Art Society.[24]

In honour of her work at Cherry Farm, the community swimming pool was named in her honour. She attended the opening ceremony.

On 4 January 1983, Moana Gow passed away at Orokonui Home at Waitati, aged 85. Her legacy continues in her family – many of her grandchildren and great-grandchildren have Moana in their names. Moana was a “very loving person, everybody loved her. Not only did she bring up her own four children and three stepsons but worked and care for her ill husband. We all loved her.”

[1] NZ Medical Journal Obituary; Anderson Family Tree; Newspaper Obituary; Natlib.

[2] Newspaper Obituary; Email Correspondence with Dean Goodman.

[3] NZMJ Obituary; Interview with Alwyn Dolling; Email Correspondence with Dean Goodman.

[4] From Email Correspondence.

[5] Interview with Alwyn Dolling.

[6] Email Correspondence with David Allan.

[7] NZMJ Obituary; Email Correspondence with Dean Goodman.

[8] Interview with Alwyn Dolling.

[9] Interview with Alwyn Dolling.

[10] Interview with Alwyn Dolling.

[11] Newspaper Obituary

[12] Interview with Alwyn Dolling.

[13] Winton Heritage Trail Brochure

[14] Newspaper Obituary

[15] Otago Daily Times, May 2-3, 1946.

[16] Interview with Alwyn Dolling

[17] NZMJ Obituary; Newspaper Obituary

[18] Interview with Alwyn Dolling

[19] Interview with Alwyn Dolling

[20] NZMJ Obituary

[21] Newspaper Obituary

[22] Newspaper Obituary; NZMJ Obituary

[23] Interview with Alwyn Dolling

[24] NatLib (https://natlib.govt.nz/records/22478183)