This biography is primarily based on the two autobiographies written by Margaret Guthrie: An Enduring Savour and Different Stars for Different Times: Memoirs of a Woman Doctor.

1951 Graduate

Contents [hide]

Growing Up Between Suva and Auckland

Margaret Winn Hoodless was born in the 1920s in Suva, Fiji, to Dr David Winn and Hilda Hoodless. David was renowned for being the Founding Tutor and later Principal of Central Medical School of the South Pacific (renamed to Fiji School of Medicine in 1961), which trained rural medical practitioners. Due to her father’s vital position in this school, Margaret spent the majority of her childhood in Suva. Her mother had also wanted to become a doctor but her parents did not have enough money to pay for boarding fees on top of the tuition fees so she was forced to choose something available at Auckland University College. Thus, she trained in education and, at the time Margaret was born, she was working as the Headmistress of Suva Girls’ Grammar School.[1] During the holidays, the family would take a boat to Auckland, New Zealand, where her grandparents lived. They had a house on the Dilworth Trust land with a verandah that looked over the Dilworth playing fields.

Margaret remembers these holidays in Auckland fondly. She got on well with her grandparents, who were kind and gentle, with a quiet sense of fun. Her grandfather was a methodist preacher who had previously worked for Wilson and Horton, the publishers of the Herald newspaper. She remembers in the early days they would shop frequently, as it was not easy to keep food. Later, her grandmother got a tabletop refrigerator to keep milk and meat fresh and then in 1935, they got a gas-heated water cylinder. She remembers her grandmother being delighted about these two new editions. And this was not the only exciting thing to happen. In the summer of 1934-5, Margaret’s aunt (who lived with Margaret’s grandparents) hired a car and took her away on a girls’ weekend – she felt “terribly sophisticated sitting beside my aunt. In those days the only family who actually possessed a car were Uncle Jack and Aunt Edna Garland who lived in Thames at that time”.[2] They travelled to Rotorua, went bathing, ate fancy breakfasts and went swimming in the lake. Her grandparents’ house felt like a second home to her and she really enjoyed her quiet childhood. She was never surrounded by many children either in Suva or Auckland but did not mind as she was content to be interacting with adults or quietly reading.

For a year and a half from September 1934 to the end of 1935, Margaret attended Fitzroy School, which was a small preparatory school that comprised approximately sixty girls. It was located in Epsom and Margaret boarded there while her father was on leave from his position at the Medical School and her mother was in India. Margaret was sent here as it was close to her grandparents, which meant she could stay with them in the holidays. She found the transition from life in Suva where she was an only child operating in a largely adult environment to a place filled with lots of children difficult. She struggled to make many friends, though she did become close with Hariata Te Au, a niece of Princess Te Puia of Tainui. They would play monopoly and spend time walking up Mount St John. She believes that they bonded over shared homesickness. She also became friendly with a girl named Beth who would invite her to stay with her family in Titirangi during the holidays.

The school had a good reputation and she did not mind it too much, though she was extremely homesick. She constantly wrote home (every Sunday it was an expectation that the borders would write at least one letter) and her parents would write back to her, sending “exotic” parcels from their travels. The food was good and the teachers were enthusiastic about teaching, which enthused the children. She managed to stay out of strife for the majority of her time there, though in her last term she found an abandoned bird’s nest, which she brought back to the home. Miss Nancy, the teacher, was horrified and banned Margaret’s next free weekend and forced her to help in the garden for three weeks.

Their Home in Suva & Being Surrounded By Medical Influences

On 1 August 1935, Margaret received a letter stating that her father’s leave was coming to an end and they were shortly going to be back in Fiji. So that she did not have to transfer school halfway through the year, she remained at Fitzroy until the end of 1935 and then joined her parents back in Suva so that she could complete her final year of primary school in Fiji. She remembers the boat trip from Auckland to Suva vividly; the departure was delayed by “wharfies” who were protesting an industrial grievance and she remembers thinking that these protesting grown men looked undignified and foolish.[3] Meal times were at set times throughout the day and at 10am everyday the children’s rooms were all inspected for cleanliness. There were many activities, including a Christmas party, and none of the children ended up sea sick. One day, Margaret and her friend Vivienne Fenton entered the dining room early for afternoon tea and saw some egg sandwiches laid out. They started to take some but were caught, swatted on the legs with a tea towel, and sentenced to stay out of the dining room until dinner time.

While her father had been on leave, the Medical School had built a home for the Principal of the school. As he had just taken up this position, and he was the first person to hold this position full-time, they were the first family to move into it. It was quite a nice house made of weatherboard and it had a large lawn with exotic flowers and trees. The family would have paw-paw, avocados, mangos and other tropical fruits from their own trees with meals and as snacks. They made ice cream from a granadilla vine and occasionally had eggs, depending on their availability. For all other necessary items, they had a butcher, baker and dairy delivery and on Saturdays they visited a local market. This trip was particularly exciting because while they were shopping they would bump into friends and spend much time talking.

Margaret had a carer named Alite (the Fijianised version of Alice). Alite fondly called Margaret Makareta, and she would often take her to Albert Park to watch the Medical School rugby team play. She also taught Margaret to sit Fijian style cross-legged on the ground. She later realised that this was not easy for everyone to do, because when she returned to New Zealand, she found she was the only one in the boarding school who could sit this way.

For her final year of primary school she attended Suva Girls’ Grammar and Alite would walk her there every morning. One morning they bumped into a man who had recovered from leprosy but had lost his nose in the process. It gave her a great fright, as this was the first time she had seen the effects of leprosy up close. In fact, she was familiar with the sight of leprosy, but only from a distance. Their house was not far from the leprosy isolation huts that had been set up for those waiting to go to the Makogai, “a beautiful, uninhabited island nor’east of Levuka, the old capital, was purchased had facilities built and opened as a leprosarium in 1911”.[4] From her window she saw people deliver food and leave it a few yards from the front of the huts so that they did not get too close. She remembered thinking “is it really that bad that you must treat these people so awfully and differently?” “Was it really so catchable?” However, over time, she learnt that the Europeans in Fiji wanted those with leprosy to be “out of sight, out of mind”.[5] She later learned that Makogai was closed in the late 1960s when better treatment had been developed.

As a child she received many vaccinations against smallpox and other mosquito-borne infections, such as Dengue fever. They always had to wear shoes to prevent hookworm and all bites were taken seriously so that they would not develop into a bad infection.

Her father’s role at the Medical School brought the whole family into his world. Over dinners, Margaret and her mother would hear about all of the issues and achievements that arose at the school and they knew all forty students by name (who at this point were all men; girls were only admitted in 1951). She believed that her father was the perfect person to fulfil the role of Principal as he was calm and collected but also stern and determined. He truly believed in the importance of the training and passed that enthusiasm onto the students. His position also meant that they always had ambassadors or visitors at their house. This not only introduced Margaret to the world of medicine but also taught her the difference between Western and Fijian medical practices. For example, she found out that in the Fijian belief system, you could will someone to death even without them having any previous illnesses, as they believed that illness was caused by evil spirits or wrong doing.

As the wife of the Principal, her mother was in charge of leaving personal calling cards at the Government House and other official dwellings. “One day the small devil which lurks to invade susceptible children told me to scribble comments on the inviting backs of the cards in our tray. Time has erased memory of just what those comments were other than that they were not flattering. The transgression was soon discovered and I was truly chastised, both verbally and physically. The possible repercussions, if my observations had been discovered by others, were clearly explained and it was probably a first full realisation that we lived in a humanly created fishbowl of protocol and behaviour.”[6]

Entering the medical environment at a young age had a profound effect on Margaret and is largely the reason that she later enrolled in medical school. One day, Margaret’s grandfather was skinning a rabbit and as “he discussed the anatomy of the rabbit he said: “Your daddy teaches the anatomy of people and will soon be a doctor as well as a teacher” … ” to which she responded, “Yes, and I am going to be a doctor too one day.”[7] She also had access to a large library, which broadened her knowledge of many topics.

Suva Girls’ Grammar School

Following primary school, Margaret entered Suva Girls’ Grammar School, which was an Intermediate School between Primary and High School. The school was made up of several wooden buildings and a concrete lavatory building. The classrooms had only empty holes for windows, and shutters that would stop the rain from coming in on stormy days.

By this age, her parents decided that she could walk to school on her own. However, it was not long before Margaret learnt that this was not such a good idea. One day, she was followed by a boy who was shouting very inappropriate things at her. She ran to school and told a friend, whose brother went and dealt with the boy. From then on she walked with a group of friends to school. After school, she often went with a group of friends to swim at the Suva baths.

Her time in this school was quite odd. She remembers that when the Japanese ships would dock, the sailors would barge into the classrooms and sit in the empty seats, taking photographs of everything they saw. This did not only happen in the classroom as well. One day her mother came home to find a Japanese man sitting in their living room taking photos.

Margaret does not remember much of what they actually learnt in school, though she did enjoy it and she remembers having the same teacher for Forms One and Two.

Nearing the end of Form Two, conversations began concerning where to send Margaret for High School. Her parents decided that it should be in New Zealand, as the quality of education was higher. The three options were New Plymouth Girls, Epsom Girls, and St Cuthbert’s. The decision was made to send her to Epsom Girls’ Grammar as it was close to her grandparents and it catered well for out-of-country borders.

And so, at the end of Intermediate, Margaret got on a boat bound for Auckland with every intention of returning during the summer holidays. Little did she know that this was the last time she would live in Suva, and the last time she would visit her family in Fiji for eighteen years.

Epsom Girls’ Grammar School

The boat trip from Suva to Auckland was more pleasant than her last trip. The sleeping quarters had been upgraded from bunks to beds. She was also allowed to eat at the Captain’s table because he was a good friend of her father. Her mother made this trip with her to help her settle in, and they went on a two-week holiday with her mother’s side of the family. However, not long after their return from this holiday, there was a poliomyelitis outbreak and schools were advised not to open. Her mother quickly returned to Suva, and Margaret went to stay for a month with a family friend at their bach in Browns Bay.

When it was time to return to school, she moved to her boarding house on Ownes Road, which was only a ten minute walk to Epsom Girls. She remembers that the food in this boarding house was quite average. Not much stood out to her about the first half of Third Form (her first year at Epsom) except that her mathematics mistress was the same one that had been there when her mother had attended Epsom Girls. Because her mother had been good at maths, the teacher assumed Margaret would be the same so she frequently called her out. She quickly grew to dread the daily math sessions. At a later date, her mother (Hilda) was on a train when she overheard two of Margaret’s teachers saying how unfortunate it was that Margaret was at the bottom of the class for maths and not very attractive. Her mother leaned over and said: “The important thing is that Margaret be happily confident in herself”.[8] What was ironic was that one of the teachers gossiping had been in Hilda’s class at school and had come second to her. As a result, Hilda had received the Sinclair Scholarship above her. Hilda’s comment exemplifies the Hoodless’ understanding of education: they believed that you should work hard but there was no pressure to achieve well. It was more important to put in your best effort and meet challenges head on instead of hiding from them.

Halfway through Third Form, Margaret fell sick with recurrent tonsillitis. She was isolated from the rest of the girls to prevent spread but then, one day, it turned into a rash of scarlet fever. She was rushed to an isolation ward in hospital and she was not allowed any visitors. As this was pre-antibiotics, she believes she was given either phenol and borax or an injection of scarletina anti-toxin. It was terrible. Her grandfather eventually discovered that her bed faced Park Road. He would stand on the road making gestures as if to have a conversation with her to prevent her from feeling so alone.

Unfortunately, the rest of this year did not improve. Due to the illness, Margaret missed half of the school year and she had to repeat. Furthermore, her trip to Suva was cancelled. Hilda resigned from the Correspondence School where she was working and she moved into a flat next to Epsom Girls’ with her sister. Hilda’s father then caught pneumonia, from which he soon passed away. Not long after this, her mother suffered a heart attack, which left her physically impaired, and then a few months later she had another heart attack from which she passed away.

That Christmas, Margaret’s father came to visit her and announced that he was going to tutor her in math. She said that he was a calm and loving teacher. He taught her in the morning and then left her with some exercises. Because of this, her grades rose exponentially.

In her second year at Epsom Girls, war broke out and her parents were forced to stay in Auckland rather than risk a boat-trip back to Suva. It became a daily habit for them to listen to the 9pm BBC News radio update. Despite the outbreak of war, school proceeded as per usual. Her favourite subject was English and, because she intended to go to Medical School, the head of science organised for her to have separate physics lessons. She was also given the opportunity to take extra-curricular lessons, for which she chose piano and choir. Her highlight of the year was performing in the Auckland Secondary Schools’ Choral Concert. She remembers one incident in music class when a Jewish girl quietly excused herself from singing “God of Nations At Our Feet”, which at that point was not the national anthem. The teacher verbally abused the girl, essentially calling her a traitor. Margaret stood up for her, informing the teacher that she was being extremely unfair to one whose family narrowly escaped such intense persecution in Germany.

In 1941, Margaret sat the Cambridge Entrance Examination – she was only one of two in the whole of New Zealand. She said that it was no harder than matriculation. Her intention had been to travel to Britain for medical school, however, her family decided that due to the war it was safer for her to stay in New Zealand. Her father was quite disappointed about this, but by this time, Otago Medical School had a good reputation and her mother did not feel too bad about sending her there.

Medical Intermediate at Auckland University College

During Margaret’s final year of school, she confirmed that she did indeed want to go to medical school. Though a lot of people joked that she was merely following in her father’s footsteps, she felt that she was more influenced by the students at Central Medical School and their infectious enthusiasm: “The students of those days were so keen. Their enthusiasm was infectious. That enthusiasm made a huge impression”.[9] Thus, Margaret enrolled in Auckland University College for her Medical Intermediate year, which she started in 1942.

Margaret thoroughly enjoyed her social life during this year of Medical Intermediate. On the one hand, it was a shock to the system, as she had spent her whole schooling life in single sex schools and she was an only child. She attended the freshers’ ball but “barely survived” the evening and was never asked to dance. On the other hand, during this year she found enjoyable pastimes, such as the University choir, which gave her a welcome distraction from her difficult classes.

Her cohort in Medical Intermediate was very limited. There were few male students due to conscription for the war – only those studying “essential” subjects (i.e. medicine and dentistry) were allowed to stay at university. Likewise, she found the demographic to be largely Caucasian. There were few Māori students, and even fewer of Asian descent.

Not only did the war affect the demographic of the intake, but Auckland society itself was disrupted by it. During this year, Auckland experienced the “American Invasion”, in which American soldiers frequented the streets and US military hospital buildings were established on Market Road. Margaret explained that she became aware of prostitution for the first time and even saw it happening in broad daylight on the city streets.

Academically, Margaret did not perform as well as she had hoped. She struggled with physics, so much so that when the results came out (which were published publicly), she was embarrassed to find that she had failed the paper by only a few marks. She was given the opportunity to sit a “special” at the end of summer break and so she spent the whole of December and January preparing for it. She received some good coaching which not only made physics easier, but more interesting.

After sitting the special and discussing her options with her father, Margaret decided to pursue a Bachelor of Science (BSc) rather than enter into a Medical Degree. She felt that she needed more time to prepare and she also felt quite young to be a doctor. Though she had been offered a spot at the Medical School, she turned it down. She later found out that one of the lecturers at Dunedin had not received the response and had placed her on the roll. When conducting the roll call, he called her name and someone who knew her from Auckland said that she had chosen to do a BSc instead. “Dr Ellis did not forget. It was to be 1946 and another roll call when the name Margaret Hoodless was called. A response drew the comment: “Welcome, you are here this time”.[10]

Bachelor of Science in Auckland

In 1943, Margaret began her BSc. Unfortunately she could only cross-credit Stage One Chemistry and Zoology. This meant that she had to sit Stage One Physics and Maths. She remembered that she was one of two women studying physics at the university and they were even told that this was the first year they had two women students in physics. Margaret was able to gain help in Math through some friends she made through the Auckland University Tramping Club. Though she did not particularly like sports, she was invited to join by fellow students and she quickly fell in love with it. The club was filled with all kinds of people: some people went on the tramps to look for specific botanic specimens or terrain and so the social trampers learnt a lot from them. Some others loved classical music and jazz and so introduced the others to the Friday evening “hops” in the Students Union Building.

At one point, they were building a hut in the Waitakeres and were in need of an oil lamp, as most had gone overseas for the war effort. Margaret mentioned that her Aunt Mary Adlington had one. At the mention of Adlington, another student mentioned that there was an Adlington who had won a double first class honours in Maths and Botany. Upon looking into it, Margaret found that it was her mother who had achieved this!

In the 1943-4 summer vacation, Margaret got a job in the market gardens, as the men who had been working there were in the Pacific for the war effort. She was bused to the gardens each day and worked long hours in the sun. One day she came home vomiting with urticarial welts all over her body and aching joints. It ended up being Henoch-Schonlein purpura, most likely from the sprays. She was well enough to go back to university the next year but she was quite weak and was unable to participate in the Tramping Club. Instead, she was elected to the Women’s House Committee executive and spent the majority of her time selling and distributing Craccum, the University’s Students’ Magazine.

The next few years of her BSc were largely defined by world events. “Being wartime it was a period when student numbers were comparatively low generally and the climate encouraged a collegiality heightened by everyone being to a lesser or greater degree affected by the tensions and tragedies that war imposes on those who remain behind, as well as those who are directly involved.”[11] She remembers vividly the day the war ended and the news that Hiroshima had been bombed. She mentioned that Victory Day, the day after Germany surrendered, “was a day such as none of us had experienced before. Our world stopped work, lectures ceased, except for essential services we all partied. We danced in the streets, drank bars dry; everywhere people celebrated. A sense of euphoria prevailed – and it took a couple of days for normality to return.”[12] And then the news about Hiroshima was announced moments before a Stage Three Physics lecture. Professor Burbidge (the lecturer), had worked with Rutherford at Cambridge: “To him the news was proof that the atom had been sundered.”[13]

Overall, Margaret was thankful to have taken the extra time to do a BSc as it gave her the proper foundations required for entering Medical School. She also made some lifelong friends during her time there, one of whom entered Medical School with her – Phil Allingham.

Margaret’s First Year at Medical School & Marrying John

Margaret’s mother, Hilda, was still in New Zealand during the months before Margaret began medical school. During World War Two, her father had returned to Suva and they had been living separately. Unbeknownst to the family in New Zealand, his chronic illnesses had been worsening. However, without telling them this, he advised that Hilda should remain in New Zealand a bit longer. So, Hilda travelled to Dunedin with Margaret to help her settle in. On the trip from Auckland to Dunedin, they stopped for a few days in both Wellington and Christchurch to see family friends. In Dunedin, they were met by the new head of the Otago Girls’ High School, Miss Margaret Fitzgerald, who was a friend of Hilda’s. Unfortunately, she only had a small flat and could not put them up, so organised for Hilda and Margaret to stay temporarily with Dr Moana Gow (nee Anderson). Moana was lovely and helped them to feel at home in Dunedin. Margaret ended up boarding at her home until she found a long-term place to stay. Even after she left her home, Moana continued to mentor her.

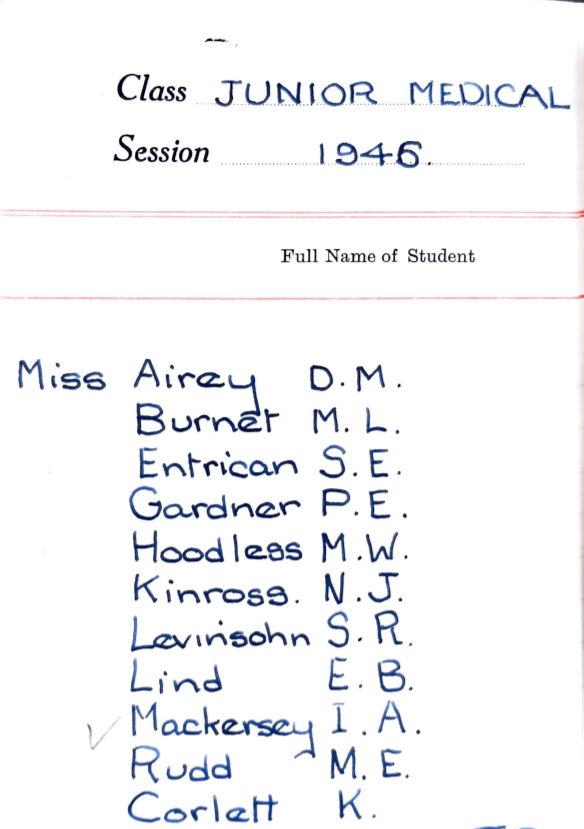

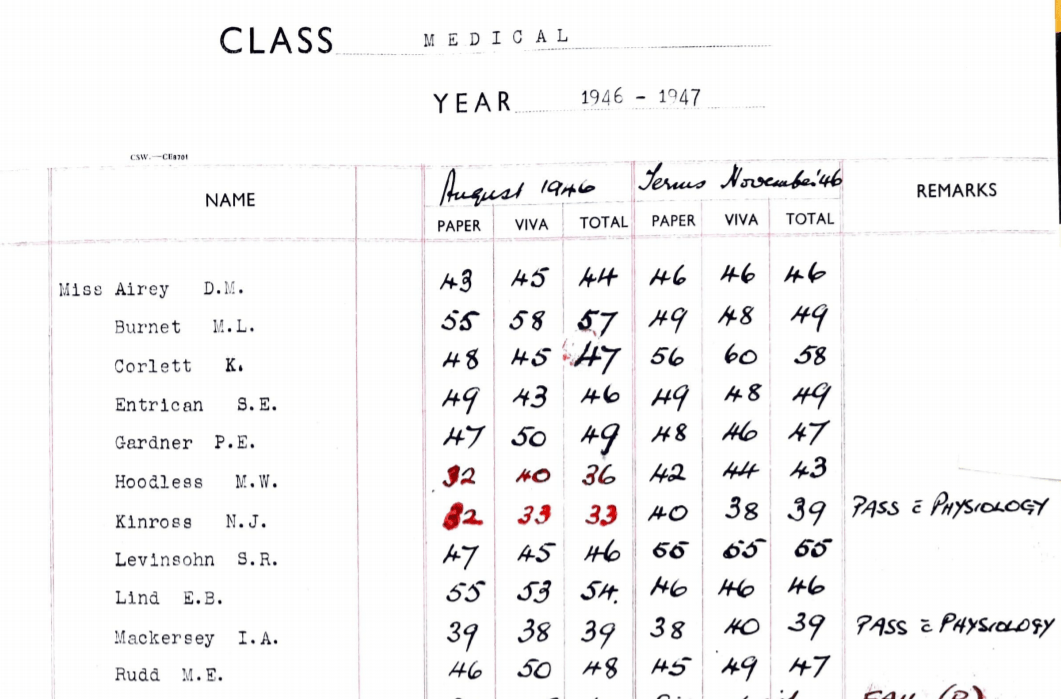

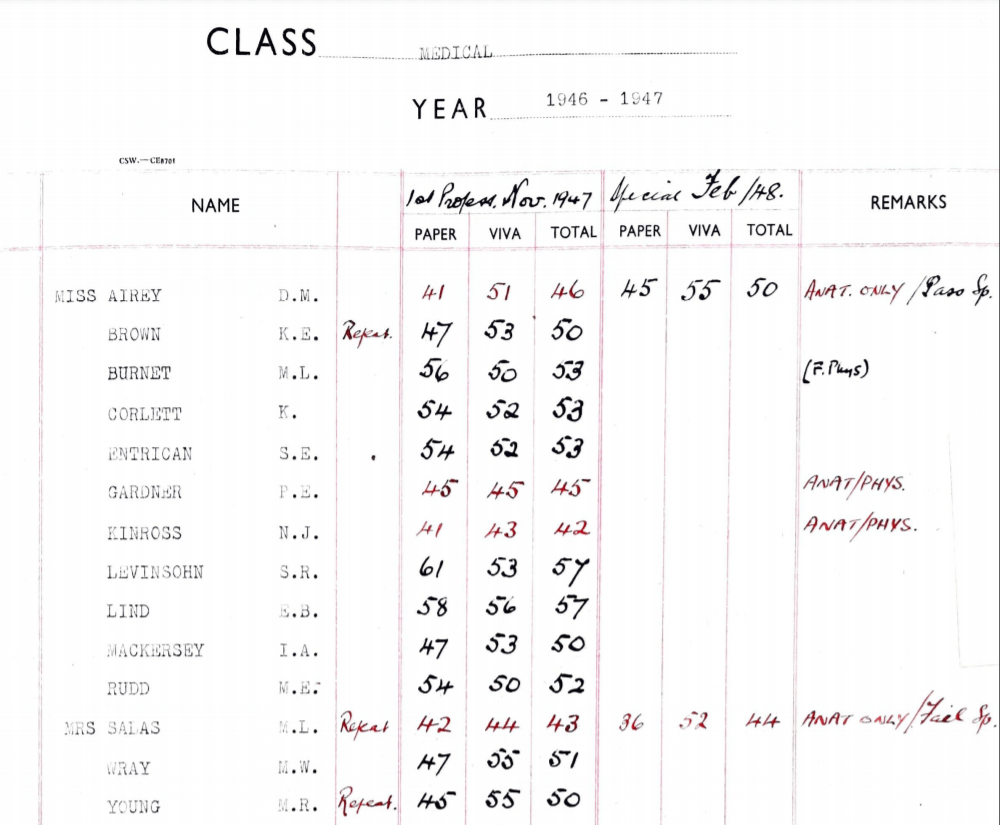

Margaret was one of ten women (among 120 admissions) to enter Medical School in 1946 and they were informed that they were expected to sit in the front row “under the immediate supervisory gaze of the lecturer to presumably protect precious males from the risks of female proximity.”[14] She refused to sit in the mid-section of the lecture theatres, rather choosing to sit on the side closest to the door. The women were also separated out in the dissecting rooms and given cadavers who were burn victims from a fire at the Seacliff Mental Hospital. The women and men medical students had separate common rooms and it was not until they were trainee interns at Dunedin Hospital that they were given a mixed-sex common room. Overall, her first year of classes went relatively smoothly and she had some good teachers, though she does not remember specifically what she learnt.

In this first year, she spent most of her social time with Moana’s family and then with Olga Spain, a war widow with a five year old son who she went to board with.

The majority of the intakes in her class were returned servicemen from the war. One of these men was Johnnie Wray, who was repeating his second year of Medical School due to getting sick during his first attempt and subsequently spending the rest of the year in hospital. She met John at a party hosted by a mutual friend. John had volunteered for the army on his 21st birthday – 4 July 1940 – and sailed to Egypt later that year. During his time overseas, John was wounded in his thigh. He spent two and a half years in hospital where he developed Crohn’s disease and a Tuberculosis Lesion was found in his Chest X-Rays. Upon return to New Zealand, he was put forward as one of the first candidates for the new drug, penicillin. Though he recovered, his medical injuries were to plague the rest of his life.

His medical injuries inspired him to transfer from his accountancy degree (which he had started before going to the war) to a medical degree. “He said himself that there were those wounded who virtually turned their face to the wall and one knew they would succumb, and those who defied disability and had a better chance of survival. He was certainly one of the latter, a person who lived as if every day mattered, reflective, at times a trifle cynical but always with a great sense of fun and confidence.”

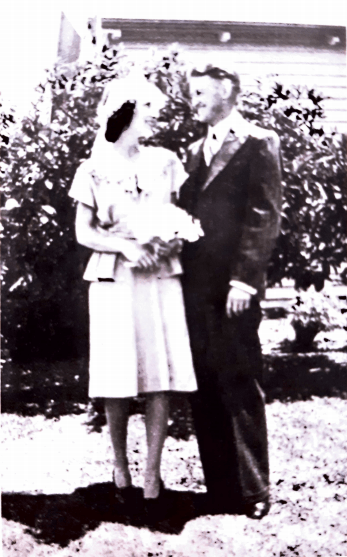

After spending much time together, John wrote a letter to Margaret’s father asking for his permission to marry Margaret. At the same time, he sent a letter to his parents indicating that they were planning to become engaged. His mother was so excited that she put an announcement in the newspaper without telling Margaret and John – they were not even officially engaged at this point. Unfortunately, Margaret’s father received a copy of this newspaper before he received the letter, which definitely coloured his response. He advised that they should wait a year and a half so they could focus on their studies and specifically so that it would not impact Margaret’s studies. He also commented rather dryly on how it appeared they believed the parents’ blessing did not matter. He said he would only give his blessing if they agreed to wait. Unfortunately, by the time the letter arrived back John had purchased a ring. After finishing the year, they both decided that they did indeed desire to marry each other. She wrote to her father hoping for a change of heart, but there was not. Her father even wrote to the Dean hoping that he could persuade her and even used the “John’s health is bad” card. But the Dean essentially said to her: ‘Tis better to have loved and lost / than never to have loved at all.’[15]

Despite her father threatening to put an end to the money he was sending Margaret if they got married, the couple settled on the date of 2 February 1947 at Pitt Street Methodist Church. As her parents could not be there, Margaret’s aunt organised the wedding and her Uncle Jack gave her away. She subsequently applied for a Medical Bursary and was granted it, with the only condition being that for her first two years post-graduation she had to work wherever they placed her. Incidentally, she was never contacted about a placement and so did not have to fulfil this requirement. The couple honeymooned at a friend’s bach in Taupo before returning to Dunedin and settling into a small apartment above the University bookshop.

Back row (from left to right) – John Wray, Nelly Wray, Jack Wray, Edna Garland, Jack Garland.

Front row (from left to right) – Margaret Wray, Thelma Wray, Molly Garland (nee Wray), Mary Adlington.

Medical School as a Married Woman

The early years of married life at Medical School were tight for the couple. Though they had Margaret’s medical bursary and John’s returned servicemen rehabilitation bursary, between rent and bills they often had very little money left over for food and clothing. She quickly learnt that she did not know how to cook and so every week her mother sent her new recipes and she bought a good cookbook that taught her all of the basics. What compounded their financial situation was that due to John’s illness, he could not do many of the hard labour jobs that most students sought during the summer. Instead, he worked for a railway repair company, which he still found quite hard. To help lift the financial burden slightly, Professor Adams offered her a lab tuition position in the haematology lab after discovering that she had a BSc.

Margaret received much criticism for being a married woman in the Medical School, and one of the Professors even declared to all of the students in his class that he did not think she would last the full degree. There was also talk between the women medical students who would ask her “how can you be a woman doctor and a lady?”[16] They assumed that if you married, you would drop out – which many of them did. However, Margaret commented that by this time, there were many women doctors who she could look to as role models: Muriel Bell, Marion Whyte, and Marion Stewart, for example.

In their fourth year, the students dealt with patients for the first time and Margaret felt as though she was extremely underprepared – she felt like the medical school had not taught them how to deal with actual people rather than just the symptoms. In fifth year, they had to make a quota of delivering babies and so lived at Queen Mary Hospital for about three weeks so as to fulfil this. Margaret enjoyed this three-week stint and, while it was difficult in places, there was very good camaraderie between the group. Her fifth-year public health thesis was on “Some Aspects of Menstruation” and she obtained participants from the Otago Girls’ High School. She interviewed sixty girls and found some interesting results, such as that many still believed the old myth that women on their period were unclean. These girls did not bathe when on their period because of it. The biology teacher became interested in Margaret’s work and decided to continue educating the girls after the study concluded.

Her final year was spent in Dunedin, where she was assigned a placement in the Sexual Diseases Clinic. This experience opened her eyes to how many others lived and she realised she had lived quite a sheltered life. These last months of her Medical degree were clouded with a sense of self-doubt and wondering whether or not she really was good enough to practise as a doctor. She did well in her final exams, though failed her oral exam because she froze and could not answer any of the questions. The University allowed her to sit a “special” exam in May and so she spent the entirety of her summer holiday preparing for this. Alongside her study over the Summer break, she was offered a position as Acting House Surgeon in the Student Health clinic. Meanwhile, John obtained a position as House Surgeon at Dunedin Hospital.

Hilda decided to move to Dunedin for six weeks to support Margaret leading up to her “special”. She cooked for the couple so Margaret had more time to study. Not only did this help Margaret, but it was the first time she had spent a long period of time with her mother since she was an adult. She says that this was the first time she got to know her mother properly, learn how incredible she was, and how much depth she really had. Thankfully, Margaret passed her “special” comfortably and she graduated in 1951.

Early Career and Starting a Family with John

Only a few months after sitting and passing her “special” exam in May, Margaret found out that she was pregnant. She continued to work throughout her pregnancy, though much fewer hours than John. At the end of 1951, the couple moved to Southland Coal Mining for a locum and Margaret only did a few of the calls and deliveries, usually when John was away on another call. She also worked as the dispensing chemist because there was no one else to do the job.

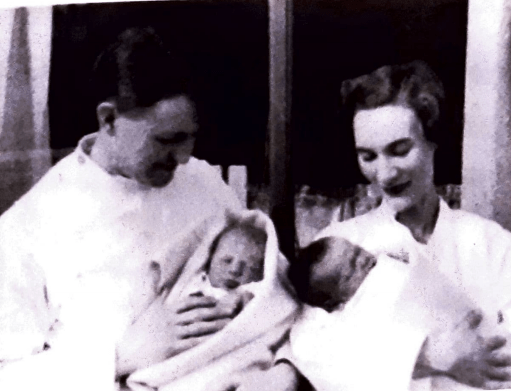

Following this locum, the couple were offered to housesit their friend’s farm while he was in Britain for a postgraduate course. They accepted as it provided them more space for when the baby was born. The farm had chickens which provided eggs and a local farmer looked after the sheep. Their first daughter was born 1 March 1952, only two months after they moved into the farm house.

At this point, John and Margaret hit a cross-roads. John was keen to do some further study and Margaret wanted to become a Radiotherapist, yet they now had a child. They decided to settle in Havelock North, where John became a General Practitioner while they decided what to do. Margaret eventually decided to delay her Radiotherapy studies so that she could work with John. Working as a GP gave her the opportunity to work part-time, which she started after having their second daughter in August 1953.

When they established their practice in Havelock North, there was only one GP in the area. On their first day, no patients turned up until late in the day when a young boy walked in with a burnt hand from a firecracker. He later explained that he came here because he was afraid to go to the former GP because he would tell on him to his parents. John informed the boy that he too unfortunately had to inform his parents. The practice slowly expanded and in the mid-1950s the GPs in the area all came together to form a roster of evening and weekend visits so that they were not all overworking and undersleeping.

The Wray’s found the people in Havelock North lovely and the place had a good community feel. Their patients were very generous and the butcher once gave them a leg of lamb for free. Margaret helped run a fundraiser to build the first kindergarten and when Margaret started working again, their next door neighbour helped with the housework, phone calls, and childcare.

When the practice started to get very busy, they hired a 16 year old girl (who had finished school early to look after her ill parents) to be their receptionist. They also bought the empty plot of land next to their house and started building a dedicated surgery. The new surgery had a proper waiting room, reception, and two patient rooms.

In 1955, Margaret received word that her father’s health was deteriorating quickly and so she flew to Suva to be with him. He tragically passed away from his chronic illness on 15 April 1955. Her mother moved to Havelock North to be near Margaret but when she arrived, she was quite poorly. A local doctor in Suva had diagnosed her with grief but upon seeing someone in New Zealand she was diagnosed with lymphosarcoma, from which she died on 31 December 1956. Losing both of her parents in such a short time caused Margaret to examine her life. She became quite sad that her children were growing up without cousins and in such a small family. Though John did not initially agree due to his unstable and unpredictable health condition, the couple eventually decided to have another child. Margaret gave birth to their first son David in July 1958.

Margaret’s parents were not the only ones close to the Wrays who passed away in the 1950s. Just as these deaths caused Margaret to examine her life, the death of one of John’s closest friends in the late 1950s caused him to examine his life. He decided that seeing up to 60 patients each day was not good for his health and stress levels. So, in March 1960, the couple sold their practice in Havelock North and moved to the United Kingdom for an OE. Tragically, John’s father passed away while they were on route to Europe and they did not have enough money to turn back for the funeral. The children also got very sick on the boat trip (David with an E. Coli bug and their second daughter fractured her fibula in a fall) so Margaret spent the first few months in England looking after them instead of working.[17]

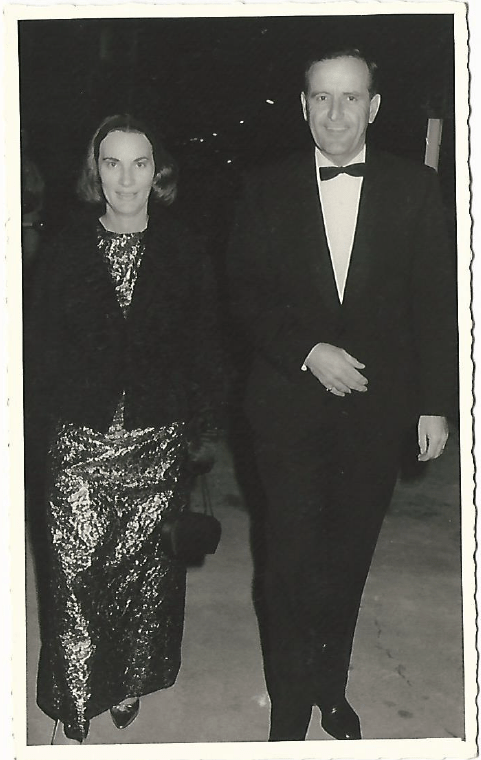

They initially moved into her aunt’s house in Cambridge but later bought a house in Merrow. John undertook postgraduate study in pathology, they traveled a lot, and they had a brilliant social life. At one point they were invited to the Medical Graduate’s Dinner at Oxford, which introduced them to many people in the medical community in England.

After one year in England (1961), Margaret noticed that John’s health was declining. However, he persisted with his studies. John was due to finish his studies at the end of 1962 and so he began the process of applying for a job. He decided to apply for the position of Pathologist at Princess Margaret Hospital in Christchurch, New Zealand, however, his medical examination came back with some concerning results. Margaret remembers John coming to her one day while she was sitting on the couch and saying to her: “Please feel free to marry again and be happy. I don’t want you to feel tied to memory of me.”[18] She was left dumbstruck, but they never had another conversation about this.

A few days later, he informed her that he was going to test drive a car that he wanted to bring back to New Zealand with them. At 5pm that evening Margaret received a call urging her to come to the Hospital as soon as possible. John had had a massive cerebral bleed and was on life support. He passed away on 24 February 1963.

Returning to New Zealand & Joining the RNZAF

During John’s postgraduate studies, Margaret had started to become restless as a stay at home mother. She had written to the Secretary of the New Zealand Branch of the British Medical Association, asking about any employment opportunities. The day her letter arrived, he happened to be meeting with the Director of Medical Services in the Royal New Zealand Air Force (RNZAF), which was short of medical officers. With the secretary’s return letter came an offer of a position at the RNZAF Woodbourne Base for three years. The RNZAF also agreed to pay their return airfares and shipping costs back to New Zealand.

John then tragically passed away, reinforcing the need for Margaret and the children to return to New Zealand, where Margaret could work to support the family. Their return trip took them to Fiji where they had a few days relaxing and Margaret could show her children where she had grown up. Margaret says that these few days were needed, because as soon as they landed in New Zealand they had to visit all of John’s family members between Auckland and Hawkes Bay to deliver the news and grieve with them. She went straight from this to her first day of training for her job at the RNZAF. “The next morning I attended the Base Hospital, the assembled staff being presented in turn. Then I was shown the door of the MO’s office cum surgery, though no one came in with me. On the desk was a framed Giles cartoon in which a military officer lent on his stick while a Sergeant bent over beckoning towards bright eyes peering out from under a building saying: “Come on – be brave soldiers – there’s no ’arm in an inspection by the new lady MO”. I laughed out loud at which the Sergeant and Nursing Sister came in remarking: “We wondered how you would react. Would you be happy for it to be hung outside your door?” It hung there for over a year.”[19]

Her primary task as Medical Officer was looking after the health and wellbeing of the boy entrants (many of whom suffered homesickness) and delivering the sessions on sexuality. She was also tasked with inspecting all of the facilities to ensure that they were up to standard. One building that was particularly of concern was the Sergeants’ Mess. After sending multiple reports of the low hygiene standards, Margaret “decided that it was time to ‘throw the book’. The Commanding Officer was informed in writing, which was personally delivered, that unless the Sergeants’ Mess showers were replaced forthwith the Mess would be closed on public health grounds. The response was immediate.”[20]

After one year on the base, one of her concerns was that, whereas officers were entitled to an annual medical, lower ranks from boy entrants to warrant officers only had an entry medical and no further regular follow up assessments unless they were to deploy overseas. Many of these men had been taken on in the 1940s and 1950s and had barely ever visited a doctor since. “After some discussion with the President of the Sergeants Mess, all Warrant Officers and NCOs were offered a full medical to ascertain their health status and follow up if anything untoward emerged. I no longer have a copy of the report that eventually went to Defence Headquarters but do recollect that around a quarter had some degree of hypertension, one had undiagnosed angina which he thought was indigestion, a couple were diabetic and one had aortic valvular disease which responded well to surgery. Consequently it was agreed that a screening examination should be offered to all personnel on a regular basis.”[21]

Margaret ended up with a fairly supportive group around her; she was introduced to the local GP who was also a part-time farmer, and the charge nurse at the local Accident & Emergency. They were both supportive allies in difficult circumstances.

Marrying Walter Guthrie & Leaving the RNZAF

Margaret had heard much about the 39 year old bachelor called Walter Guthrie, who was a Sergeant in the RNZAF. Upon meeting him, Margaret likened him to a “a sensitive 13 year old who grieved when his father died suddenly from a heart attack, the youngest of three siblings, whose boon companion in boyhood was his spaniel, Darkie.”[22] Margaret and Walter started spending a fair amount of time together at social events off base. Unfortunately, on December 23rd, a Squadron Leader administrator turned up at her house and informed her that it was unacceptable for her to be dating a Non-Commissioned Officer (NCO) who was “socially beneath me” while she was a Medical Officer, even though she was technically a civilian. “We should have, I was told, individually driven out of the base and met up well out of sight at Onamalutu. That made me expostulate: “I’m 39, with three children. If you think I am going to take to the bush at this stage of my life to meet a man you’re mistaken”.”[23] The consequence of this tense conversation was that Margaret and Walter were confronted with the nature of their relationship. They either had to form a serious relationship earlier than what would have occurred naturally, or return to a friendship.

Margaret took it upon herself to challenge the current system at the RNZAF both to confront its contradictory nature and to secure herself a permanent position. In one discussion with the Air Commodore, she commented: “my male colleagues quite often married nurses and in their view we should be reversing the gender roles, a male nurse marrying a female doctor.”[24] He responded by saying that if she married Walter, her employment would cease. Margaret was called to Wellington to have a meeting with the Secretary of Defence to discuss this issue further. The meeting concluded with the same result: “in their view the best option would be for me to resign from my position. Remembering my advice I responded: “I shall seek legal advice about that request.” The expressions on some faces immediately indicated that the response was not what they wished to hear.”[25] A few days later, Margaret received notification that her contract would continue should she choose to marry Walter, though they had to live off-base so that their marriage, which was still considered a breach of protocol, would not be visible from the base. “The CO did discuss with me what might happen if, as head of the medical unit, an incident might occur which called for discipline of the NCO in charge. I responded that I could only truthfully answer that after any such occasion, but that I was sure ethics would ensure an appropriate response, which was accepted.”[26]

Both sides of the family had their concerns (both about whether it would be a lasting marriage and if enough time had passed since John’s death), Margaret and Walter married on 28 March 1964. Though there were restrictions on what they could do and where they could go, the first few years of their marriage were very pleasant.

In April 1967, Walter’s 24 year contract with the RNZAF ended and, instead of reapplying, he decided it was time to move on. A position as medical records officer became available at the Princess Margaret Hospital in Christchurch and Margaret was able to transfer to RNZAF Wigram. They bought a house in Papanui and, though she was only at the base during working hours, she felt comfortable in the community of people around them. The move to Christchurch also enabled her to join an active branch of the New Zealand Medical Women’s Association, where she was elected as Secretary from 1960-69.

Halfway through 1973, Margaret started to feel that it was time to move on, as there was no room for professional development in her current role. She considered becoming a GP, however she wanted to be on salary, as “being salaried freed one from any financial issue affecting one’s care and attention, including the allocation of time for a consultation.”[27] She came across an article in the Evening Post advising of the difficulty of the North Canterbury Hospital Board in finding a Medical Superintendent for Burwood Hospital. This post seemed interesting and so Margaret set up a meeting with Dr Ross Fairgray. Dr Fairgray advised her that “there had not been a female medical superintendent in Christchurch, and he had no idea how the Board might react to such an application”[28] and advised her to discuss this with the doctor in charge – Dr Berry – who ended up being very encouraging and advised her to apply.

When called in for an interview for the position, Margaret was greeted by a circle of men, “all of whom bar one, the CEO, were hospital specialists”.[29] They questioned her about her time availability and mental capacity to work considering she had three children and what impact this would have on ability to be a good mother. They also asked how ten years at the RNZAF had prepared her for heading a general hospital and why there was a three-year gap in her resume where she had not worked (to which she explained she had been looking after her late husband while his health was failing). Margaret was offered the position and thus became “the first female medical superintendent of a hospital of over 100 beds in the country”.[30]

Burwood Hospital: Specialising in Health Administration & Challenging Gender Barriers

One of Margaret’s tasks was to pay specific attention to the Charge Nurses and ninety-nine long stay patients in three wards. She requested the Principal Nurse to introduce her to the staff and patients in these wards and was shocked to find that some of the patients had quite severe disabilities and had been a patient here for around twenty years. She decided that in order to optimise her ability to help, she required further training. She contacted her superiors and requested to do a Diploma in Public Health (DPH) through Otago University, however, this would have required her to take a year of absence, which they did not believe would be feasible. Margaret later heard about the newly established Massey University that was offering a multi-disciplinary, postgraduate, extra-mural course for their Diploma of Health Administration (DHA). As this only required two three-week, in-person sessions in Palmerston North and the rest could be done by distance, the Board approved her request and offered to sponsor her enrolment. She was amongst the first intake in 1974 and she found that the assignments were all directly related to issues she was experiencing in her work. “Fitting the full time work role, the study, assignments and family life during those three years was an effort, but it was worthwhile.”[31]

Unfortunately, as the DHA was a newly established course, it was not recognised by the Medical Council as being equivalent to a DPH. She sent in an application, with the support of Dr Berry, but it was declined. This meant that she was not awarded the status of specialist, even though she had a relevant qualification. “It was not until 1988 while I was representing the Director General of Health on the Medical Council, that the 1977 ruling was reconsidered.”[32] In the meantime, she was among the founding members for the College of Community Medicine, which awarded her the specialist status as a Public Health Physician.

One of the concerns that arose while reviewing the three wards was the topic of male nurses. Margaret approached a colleague, commenting that it was good that the Oral and Plastic Surgery Units at Burwood Hospital had male nurses, to which the colleague responded that “male nurses were not fully qualified in the view of the Nursing Council and she believed that should be maintained.”[33] When she looked into the matter further, Margaret found that the Nurses Registration Act of 1901 excluded men from becoming nurses and it took until 1939 for an amendment to be made that allowed male nurses to be trained and registered but only on a separate Male Nurse Register. Despite it now being the 1970s, there were still only on average two male nurses graduating each year. When asked to speak at the Community Nurses Graduation in 1974, Margaret made a point of calling this out:

“It is particularly pleasing to see two men among this graduating class. The professions are stronger when barriers of male or female dominance are challenged, whether it be by male nurses or female doctors. There are probably more psychological hurdles for male nurses than for female doctors in New Zealand. Male nurses here can take heart from their United Kingdom colleagues who established their position in the early 1960s – they lead the way in negotiating long overdue equal conditions of service. They can also reflect on the fact that their position here is more firmly established than that of their Australian counterparts. In the April 1974 Australian Hospital and Health Journal it was reported that Austin Hospital is the first in Australia to provide live-in accommodation for male nurse trainees and that many Australian hospitals are reluctant, and, in some cases, refuse to train men as nurses. Again it is important for both male and female nurses not to feel threatened by each other. To me it seems that it is only when both sides can see themselves as equal professionals that right will prevail. Our feminists might show more impartiality if they were prepared to support male nurses in their wish to be allowed to participate in maternity training. Is it really so different from women looking after men in urological wards?”[34]

Over the years at Burwood, she was slowly pushed by Dr Berry in the direction of Gerontology. “It was sometime before I appreciated what an ongoing stimulus it was to become.”[35] It did not take long for Margaret to see that something needed to be done about the increasing life expectancy age of older people, who were surviving into a frail old age but not being properly looked after. New Zealand was relatively progressive in this area in comparison to other countries, though Margaret believed “that a great deal could be done to prevent disablement and maintain function in frail older people if they are assessed, treated and rehabilitated in a timely manner.”[36]

Margaret worked with many other geriatricians to research this specific area, and led many studies to counter previous beliefs about older people, specifically around end of life care, when they should/could return to their homes, rehabilitation, and social activities and hobbies to keep them connected to others and mentally stimulated.

Margaret was elected to become the Chair of the Domiciliary Services Committee of the Nurse Maude District Nursing Association (NMDNA) and conducted a study into how effectively the NMDNA was fulfilling their objectives. She specifically looked into whether there were problems of coordination and communication on the district nursing side, if there were gaps in the implementation of services, and whether there were problems of coordination of the entire domiciliary scene in Christchurch. She found the NMDNA to be one of the best run institutions in the country.

In July 1978, the Medical Superintendent of The Princess Margaret Hospital retired. Margaret applied and was appointed to the role alongside her Assistant Medical Superintendent-in-Chief work. Along with the newly appointed Principal Nurse, Margaret helped to make some considerable changes in the hospital. However, after eighteen months, Walter and Margaret started to feel that it was time for a change. Walter wanted to move to Wellington and he “was soon offered a part time position fund raising for the rebuilding of the Outward Bound facilities at Anakiwa.”[37]

Focusing on Gerontology in Wellington

In Wellington, Margaret was employed by the Department of Health, with a specific focus on furthering policy and “planning to improve and maintain the function and wellbeing of older people”.[38] As a part of this role, she was an active member of the NZ Geriatric Society and New Zealand Association of Gerontology. Margaret was also involved in laying out their proposals to the Minister of Health in as clear a format as possible, with the pros and cons of the proposal so that it could be reviewed as thoroughly as possible. Margaret found that this work (being a civil servant) was heavily constrained by the elected government and the Minister of the day. At one point, she was told to stop attempting to reform Rest Homes during that tenure.

Despite this, Margaret pursued with her slow and often “cumbersome” changes to Rest Homes in order to improve the wellbeing of residents. She was highly aware of the inadequate physical aspects of the rooms and standards of care. Just as she had when she had begun her position in Public Health, Margaret quickly recognised that she would be most effective in her current position with some postgraduate training. She applied to undertake postgraduate studies in systems of geriatric care in the UK. This program involved visiting various hospice systems in place around the UK and Canada so that the methods could be witnessed in action. Her leave was approved on the condition that she attend the first United Nations Assembly on Ageing in Vienna in August 1982. Her studies would also be used to draft an ‘Ageing in New Zealand’ document, as there was not currently one.

Margaret spent from May to September of 1982 visiting various care organizations in Canada and the UK that were pioneering work into the alleviation of loneliness, bereavement counselling, and social activities for older people. Margaret used her knowledge of the tools and systems she had learnt about overseas as inspiration for her work back in New Zealand. Her main driving ideas were that “no one component of a comprehensive Geriatric service can exist in isolation” and viewing the patient as a “whole person” rather than trying to treat just one aspect.[39] Much of her work was organisational in nature to balance all of the new changes she was hoping to make and in the early 1980s they were able to secure money “to fund a number of training positions for geriatric physicians”.[40] On 27 January 1983, she was appointed as the Deputy Director of Hospitals Division. She was thankful for the team members she worked with in this role as, though they all had differing opinions, they were collegial and collaborative. Part of her role in this position was emergency inspections of homes. She was often flown in at short notice to a home or private hospital around the country.

In August 1986, Margaret was appointed as the Manager of EDH (Elderly, Disabled, Handicapped), where she was shocked to hear the implication that older people were considered disabled or handicapped. Her goal in this role was to improve education, particularly that “intellectually handicapped people had the same needs for education, work and living conditions as everyone else”.[41] Consequently, she was also involved in a number of initiatives to educate about Geriatric Health. Alongside Betty Kill and Margaret Earle, they broadcast multiple Geriatric Health series through Radio New Zealand. When these ended they wrote up a service standards document in English and Te Reo.

Retiring, Yet Continuing to Work

In 1990, Margaret dropped down to part-time hours, and then from May she dropped down again to an hourly rate, working as an advisor to the Health of Older People Programme (HOPP), which she had been heavily involved with in the late 1980s. She was also involved in the Nurse Maude Association (NMA), which was based in Christchurch and specialised in “free community care for those in assessed need”.[42] Between 1990 and mid-2004, the Board of the NMA flew her down for consultations, and she felt that she was really making a difference in the lives of the recipients of this programme.

Outside of her work, Margaret and Walter lived in a house they had bought in Plimmerton which was situated perfectly in the sun. They had just moved from Khandallah and this house was (thankfully) slightly warmer. There was a local market every Saturday from early until around 9am. This market reminded her a lot of the market she visited in Suva with her mother.

Because Plimmerton was technically in the zone of Porirua, they were under the jurisdiction of the Porirua City Council (PCC). Margaret was reading the paper one day when she saw an advertisement for a meeting to discuss housing for older people organised by the PCC. Margaret decided to attend the meeting to hear what was to be said and, if possible, share her years of experience. From here, she joined the Executive of Age Concern Wellington as an honorary member. Through this, she found that most older people still lived in their own homes and were quite lonely and isolated. They established a Good Neighbour Service (GNS), where volunteers were trained to visit these people in need. Along with this came further education initiatives over the radio and instruction documents.

Between 1992 and 1997, Margaret chaired and was involved in multiple initiatives, including the NZAG, Age Concern Wellington & New Zealand, and the Ministerial Advisory Council for Senior Citizens. She was also asked to present a paper on ‘The New Zealand Positive Ageing Strategy – Its genesis and implications’ in Hong Kong in May 2001 at a Symposium on Aging. She was made a Companion of the New Zealand Order of Merit (CNZM) in 1997 and in 2001 received an Epsom Girls Grammar School Founders Award for services to medicine.

“George (Director General of Health) himself remarked that I probably did my best work after ‘retirement’ but then neither of us actually believe in retirement as withdrawing from effort. One changes direction, but to age positively, one keeps on living each day as if it matters.”[43]

Moving Closer to Family

In April 2010, Margaret moved to Auckland in order to be closer to family. Their house in Plimmerton was not entirely suitable for them as they were aging, because there were many stairs and it was quite a steep site. One of her daughters, Sarah Jane, lives in a two-storey house in Onehunga, which they converted into two self-contained apartments. Being closer to family means that she can help out with her grandchildren. Even though she cleared down her schedule, Margaret retains her life memberships, one of which was with the NZ Geriatrics Society, of which she was the first to receive: “I am delighted to inform you that you have been nominated as the first life member and this was greeted by universal acclaim. We would be honoured if you would agree to accept Life Membership.”[44]

“Have I retired now? Retirement is not a concept that resonates positively for this older gerontologist. Life changes direction at times. That can be a stimulus. There is now more opportunity and time to be with family, to cook a meal for them at times, to help develop and maintain our garden, to meet new people.”[45]

Footnotes

[1] Different Stars for Different Times: Memoirs of a Woman Doctor, p.v.

[2] An Enduring Savour, pp.20, 22.

[3] An Enduring Savour, p.25.

[4] An Enduring Savour, p.43.

[5] An Enduring Savour, p.42.

[6] An Enduring Savour, p.55.

[7] An Enduring Savour, p.15.

[8] An Enduring Savour, p.116-7.

[9] An Enduring Savour, p.123.

[10] An Enduring Savour, p.128.

[11] An Enduring Savour, p.139

[12] An Enduring Savour, p.137.

[13] An Enduring Savour, p.138.

[14] An Enduring Savour, p.144.

[15] An Enduring Savour, p.171.

[16] An Enduring Savour, p.194.

[17] Different Stars for Different Times, p.1.

[18] An Enduring Savour, p.236.

[19] Different Stars for Different Times, p.6.

[20] Different Stars for Different Times, p.9.

[21] Different Stars for Different Times, p.9.

[22] Different Stars for Different Times, p.14.

[23] Different Stars for Different Times, p.15.

[24] Different Stars for Different Times, p.16.

[25] Different Stars for Different Times, p.17.

[26] Different Stars for Different Times, p.17.

[27] Different Stars for Different Times, p.21.

[28] Different Stars for Different Times, p.21.

[29] Different Stars for Different Times, p.21.

[30] Different Stars for Different Times, p.22.

[31] Different Stars for Different Times, p.28.

[32] Different Stars for Different Times, p.29.

[33] Different Stars for Different Times, p.30.

[34] Different Stars for Different Times, p.31.

[35] Different Stars for Different Times, p.48.

[36] Different Stars for Different Times, p.49.

[37] Different Stars for Different Times, p.59.

[38] Different Stars for Different Times, p.63.

[39] Different Stars for Different Times, p.67.

[40] Different Stars for Different Times, p.97.

[41] Different Stars for Different Times, p.126.

[42] Different Stars for Different Times, p.137.

[43] Different Stars for Different Times, p.161.

[44] Different Stars for Different Times, p.221.

[45] Different Stars for Different Times, p.221.