This biography is based on questions answered by Gael’s husband, Andrew Brook, in 2020, for the Early Medical Women of New Zealand Project.

GRADUATED 1965

Contents [hide]

Early life and family: academic success at school

Gael McLean was born on 29th December 1940. She grew up in Seatoun, Wellington, and thrived at Wellington East Girls’ College where she was Dux in her final year. Her father, Archibald Louden McLean, was a partner and later fulltime clinical director of one of the two big accounting firms in Wellington. Gael’s mother was known as Jean, although her full name was Lucy Jean McLean (nee Preston). Jean was educated at Queen Margaret College and received a Bachelor of Science (BSc) at Victoria University. Despite her qualifications, employers were not interested in her degree and she struggled to secure a job. Eventually, she was employed by the Wright Stephenson company to work at a grass seed research facility, where she stayed until Gael was born. Her struggle to find employment made her a strong believer that her children should be able to succeed in their dreams. Archibald and Jean had four children: Gael, the eldest, followed by Jean, Donald and Lynne. One of Gael’s sisters, Jean, went on to gain a PhD, marry John Muddle and have two sons. Donald (known as Dougal) worked as an accountant and had three children. He died from carcinoma of the colon at the age of 63. Lynne’s career varied: she worked as a nurse and later became the secretary of “Birds NZ”. She had three children. Gael also had 11 cousins of a similar age to her, many of whom were academic. The family was proud of the successes of each of them.

The decision to study medicine: pursuing an opportunity not available to her mother

Gael wanted to devote her life to work which was both moral and useful. This vision, combined with her focus and intelligence (as well as a desire for an intellectual job), led her to believe that she was called to medicine. While the career decision was entirely her own, Gael’s family was very pleased with her choice. Her mother was “determined that the opportunities denied her would be open to her children”, while her father believed in “merit to the exclusion of all else”. The only medical role model in their family was Professor Thomas Russell Fraser, who was a very well-regarded and well-published endocrinologist at the Hammersmith Hospital in London. Being her father’s cousin, he was a distant relative, but her family was proud of him. He may well have acted as an inspiration for Gael.

Studying: learning to live away from home and meeting the love of her life

The year after Gael finished high school (1959), she began medical intermediate at Victoria University. Students were able to do this year in various universities throughout New Zealand; those with the highest grades from around the country were accepted into medical school in Dunedin. When Gael was accepted into medicine, her family was delighted with her achievement: “it was a very happy family”.

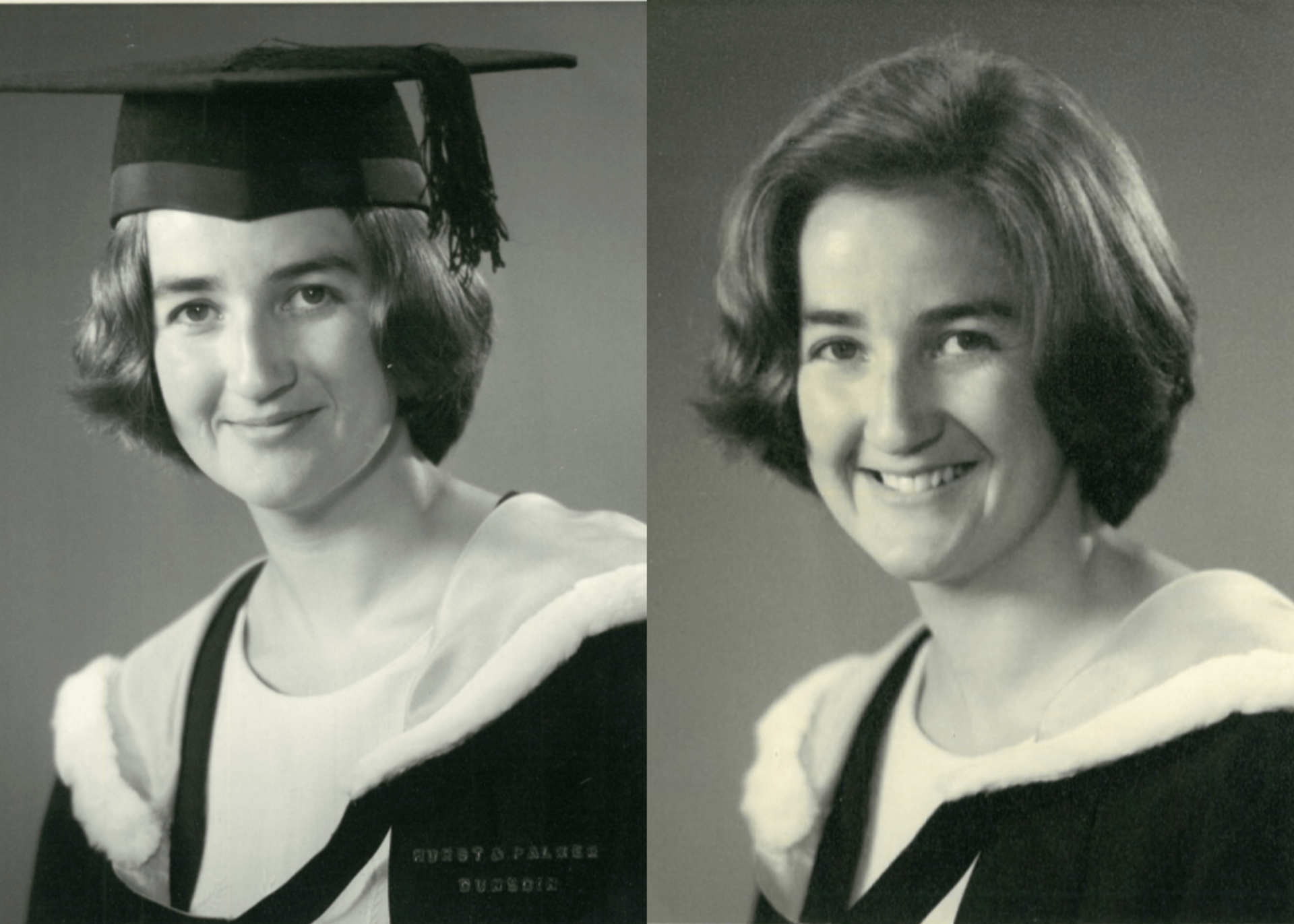

Gael’s academic ability, focus and disciplined study allowed her to “breeze” through medical school, never coming close to failing any exams. Her favourite subject was biochemistry. She enjoyed it so much that she took a year out of her degree to do a Bachelor of Medical Science in Biochemistry, which she was awarded in 1963. This is an option which is still available to medical students now, and seems to be becoming a more popular choice.

Gael spent her first year in Dunedin (1960) at a hall of residence. It had a strict curfew. The next year (1961), she moved into a flat with three of her female classmates. These flatmates had a huge influence on her, and they remained friends for the rest of her life. The group of close-knit friends chose not to indulge in alcohol. Instead, they often spent time together in their flat or went to the cinema together. Gael prioritised her studies and was not involved in any extra-curricular groups.

Naturally, it was common for students to feel homesick when they first moved to a new city. Gael managed to allay this by focusing on her studies and returning home in the holidays to see her family. Despite the physical distance between them, Gael received both emotional and financial support from her family. Andrew Brook, a fellow medical student and later husband, described Gael’s parents as “Proud sensible parents watching and encouraging three clever hard-working kids making their way through higher education.” They were willing to pay “whatever it took” to get Gael through her degree. Even with the generous financial support of her parents, Gael spent her summers teaching, which she loved to do. Her passion for the job motivated her, rather than money. During her time away from home, she gradually lost touch with the organised religion which she had been brought up in.

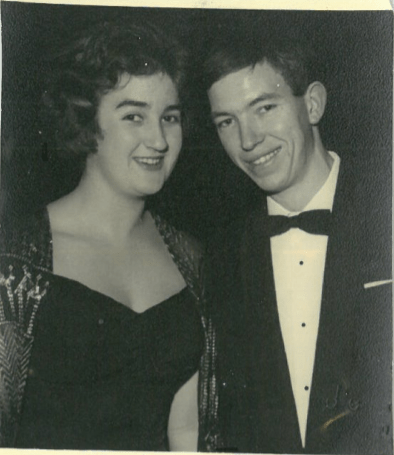

In August of 1961, Gael fell in love with a fellow medical student, Andrew. The couple married in 1964, Gael’s fifth year of study. Although it was expected that women would drop out of university after marriage, Gael kept working as hard as ever. She spent her last year studying in Auckland, where she and Andrew were able to live together in free accommodation provided by the hospital. They were not paid for the work that they did during that final year.

Gael was one of only six women to graduate in 1965, although she did not attend a graduation ceremony. The year spent on her Bachelor of Medical Science meant that she graduated with a different cohort from that she started with, which originally comprised 18 women.

After graduation: a process of elimination to decide on her specialty

Gael was a top student, so it was not hard for her to obtain a house surgeon job at Auckland Hospital in 1966. This house surgeon position was a two-year contract, split into six 3-month rotations. Through these rotations, Gael got experience working in medicine, surgery and the emergency department (ED). The pay for house surgeons was a mere £1,500 per year. In the working environment, the focus was on a person’s merits, rather than their gender, and the salary did not differ between men and women. Gael spent six very happy months in the sought-after rotation working towards a Diploma in Obstetrics at National Women’s Hospital. Under the supervision of Professor Bonham, she was awarded her diploma in 1968. Bonham treated her as an equal and encouraged her to extend herself.

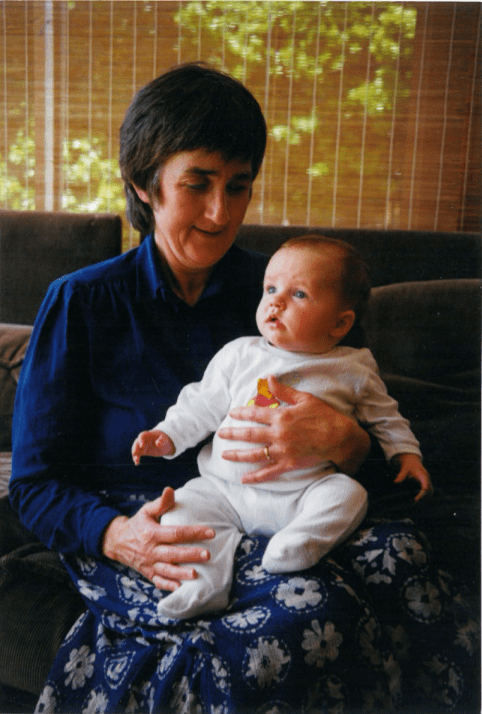

Gael and Andrew had three children – Ian, Rachael and Callum – the first of whom was born in 1968. Gael tended not to work during her pregnancies, but she did return to work after having children. She began to specialise in radiology in 1971. It was important to Gael that she would be able to train part-time while also looking after her children. This discounted most specialties including obstetrics. She also knew that she did not cope well with the stress associated with being responsible for looking after the sick overnight. Finding no appeal in administration, the decision was ultimately between radiology and pathology. Of these, she chose radiology as it would allow her to have clinical contact. Although this decision was based on pragmatism rather than passion, it was a great choice for her.

Career development: discovering the “land of opportunity”

Gael’s family moved to London to further Andrew’s career. They stayed there until Gael had completed her Fellowship of the Royal College of Radiologists examination (FRCR). The family had been intending to return to New Zealand after this, but the economic contraction in their home country meant that jobs were scarce. They travelled to Australia to find ‘temporary’ refuge, but found it to be “a land of opportunity”, which they never left. Unfortunately, Canberra, the first place they settled, was in medical political turmoil. This made it hard for Gael to find a job. She commuted to Wagga Wagga for three days a week, where she worked in a private radiology practice that was run and owned by a “wonderful woman”, Margaret Sheldon. The practice in Wagga Wagga was privy to advanced technology; a CT scanner was installed there before it was in even Canberra. Their next goal to further their technological advancement was to secure ultrasound technology. They pursued this vigorously and ultrasound grew to become Gael’s “abiding love”. Gael’s role involved servicing the Wagga Wagga Base Hospital and the big rural catchment. Although she always worked as a clinician, she also continued her teaching passion. Since Andrew was consistently secure in paid employment, the couple was always able to live off their income.

Both Gael and Andrew were specialised doctors, with Gael a radiologist and Andrew a rheumatologist. Despite the heavy workload inherent in both these professions, their family was able to make it work. Indeed, the couple must have shown their children that medicine offers a rewarding and well-balanced lifestyle, as their daughter, Rachael Bergman, has followed in their medical footsteps to become a gastroenterologist in Auckland.

Later years

Gael was forced into retirement when she developed a very slowly deteriorating neurological illness. As this illness progressed, she became bedfast and developed severe dementia. She had to go into care at Jindalee Aged Care Residence, where she was looked after wonderfully. On 9th August 2020, she passed away peacefully.

Bibliography:

- Interview questions answered by Andrew Brook

- The New Zealand Gazette. (1973). New Zealand Medical Register and Register of Specialists. Wellington, New Zealand: Retrieved from http://www.nzlii.org/nz/other/nz_gazette/1973/100.pdf

- Gael Brook Obituary. The Canberra Times. (15 August 2020).

- Royal College of Physicians. Thomas Russell Cumming Fraser. Retrieved from https://history.rcplondon.ac.uk/inspiring-physicians/thomas-russell-cumming-fraser