This biography is based on an interview with Marion McInnes (nee Hamilton) in 2021 for the Early Medical Women of New Zealand project. The interviewers were Cindy Farquhar and Michaela Selway.

1964 GRADUATE

Contents [hide]

Early Life in Auckland and Decision to Enter Medical School

On 12 December 1939, Marion Hamilton was born in Auckland. She was the youngest of five children and spent her childhood in St Heliers. Until the mid-1930s the Hamiltons had worked as missionaries in Central China and her four older four siblings were all born there. Overall, it was a wonderful childhood. Though in areas it was restrictive, her father believed women should be properly educated.

“It was a happy but very strict childhood. On a Sunday you couldn’t go into a shop or have a swim. My books were checked for suitability before I was allowed to read them. And a lot of time was spent in church. But luckily, my father was happy about education for women.”

Marion attended Epsom Girls Grammar School (EGGS), which she enjoyed. Upon enrolment, she sat an entrance examination that put her into 3AL. She played hockey and tennis and performed well in class. She chose to study sciences in the fifth form and was fortunate to have physics taught in a girls’ school. “It was a bit of a disaster though… I remember in 6A … For part of that final year there was just no physics teacher available. When I sat the scholarship physics exam, I remember looking at the questions in amazement. I had no idea how to apply the various equations I had learned to the real-life problems presented in the paper.”

One of Marion’s older brothers had studied medicine and practised as a general surgeon at Thames Hospital. “He was 10 years older than me, and I looked up to him. I think probably it was because of him that I chose medicine. At quite a young age, maybe 8 or 9 I decided I wanted to be a doctor when I grew up. So I used to say this and I think I quite liked the effect it had on people as they were mostly rather impressed. Anyway, I stuck to this idea all through my teenage years and became very determined that this was the career I wanted.” She was also sure she wanted to marry and have children, but only after she qualified in medicine.

Living Situation in Dunedin

Marion attended Auckland University in 1958 for her first year of Medical Intermediate. This allowed her to live at home. “I passed all the subjects but only got, if I remember rightly, two B’s and two C’s, which didn’t get me into medical school. So the next year I went to Otago University and repeated the year aiming for enough A’s to get in.”

Marion was not the only one from her Auckland class to repeat Medical Intermediate in Dunedin for higher marks. Evelyn Jean Mander (nee Martindale), a 1964 graduate, and Noeline Margaret Butcher, a 1967 graduate joined her on the long journey from Auckland to Dunedin. It involved an overnight train from Auckland to Wellington, the overnight ferry to Lyttelton, and the train to Dunedin. This was an exciting time in Marion’s life as she was very keen to leave Auckland. “In those days you didn’t leave home without a good reason. I couldn’t have gone flatting in Auckland. The expectation was that you lived with your parents. And though I loved my home I needed to get away and have more freedom.”

For the first two years in Dunedin, she lived in private board. “There wasn’t much money, and it was expensive living in one of the hostels.” But in her third year, she went flatting. In the flat were Marion, Jean, and two home science students. “There were four of us in a three-bedroom flat and I absolutely loved it. We took turns sharing [rooms]. Jean and I had exams at the end of the second term in August so we had the single rooms for the middle term and the other two shared. Then we shared while they had the single rooms before their end-of-year exams. That’s the sort of thing we did.”

There was a particular benefit in living with home science students: “They were very much into proper eating. We had a balanced diet and I learnt a lot about cooking and food presentation. Kind of like Masterchef. You had to have the right colours and textures on the plate. It was all very enjoyable.”

Marion was well-supported throughout her years at Medical School. She had a Higher School Certificate bursary which came to £180 a year. “And I had an uncle. My father’s family came from Oamaru where they had a sheep farm. My uncle had helped my brother financially through med school and he did the same for me. Every year he gave me £50. That plus the bursary and what I earned in the holidays [was] enough to get me through.” In the term holidays, she would go to Oamaru and stay with this uncle and aunt on their farm. “They were my father’s unmarried brother and sister who lived happily together all their lives working the farm and they were the loveliest people you could ever imagine. I always looked forward to the university holidays and spending time with them.” In the long summer break, she would return home to Auckland and earn as much as she could. She worked wherever she could get a job and this was mostly in the glassworks or in a laundry. “Girls couldn’t get very good jobs. The glassworks was best because there was some overtime. But compared to what the boys could earn in the freezing works or the woolshed it was very low pay.”

Experience of Medical School

Marion performed well enough in her second year of Medical Intermediate to enter Otago Medical School in 1960. There were 18 women in her class of 120 which was the largest intake of women the second-year medical class had ever seen. They were all quite friendly with each other and did not have any issues with the male students. Any issues were with people in the community who thought she was “wasting” the government’s when “all I’ll do is get married and have a family.” Outside of these criticisms though, “there was quite a lot of respect and I was actually quite proud to be a medical student.” The lecturers also were supportive of the women students with one notable exception, the Orthopaedic teacher. “He was awful. And he picked on the women. And he was so rude. Nobody liked him and I didn’t like him. But he’s the only one, just off the top of my head, that stands out in such a negative way.”.

The women sat where they desired in the lecture theatres and in the anatomy labs, everyone was grouped alphabetically – not separated into groups by gender as in previous years.

Marion found the clinical years very interesting. The students were sorted into relatively large groups of about fifteen and put on placements together. While this gave her good practical experience, she felt she had not been adequately prepared for the responsibilities of medical practice: “In our lectures there was nothing about our own personal response to caring for and relating to patients. When I did start practising medicine, I found the responsibility very difficult to handle and I experienced a lot of anxiety about my decision-making and competence. There had been nothing to prepare me for that.”

At times she found medical studies difficult and felt out of her depth, but she performed well enough throughout her whole time. She did not particularly enjoy the exams, but she always managed to pass. She even received a prize for her fifth year Public Health thesis that focused on the deaf community and the challenges they faced living in a hearing world. “Once I got distinction and a prize. But it was in a subject that we all tended to laugh at in those days – Public Health. We probably wouldn’t laugh today.”

Social Life Outside of Academia and Final Year Away from Dunedin

Marion greatly enjoyed her student life at Otago University. “I was very involved in the Christian Union which led to many close friends and all sorts of fun activities as well as many wonderful and life-changing student conferences.” But she did not join in many of the medical school social activities. “I think that restrictive upbringing I had stopped me. Like you weren’t allowed to dance in my house, so when they had the Woolshed Hops, which were quite events, if you couldn’t dance, it was no fun.”

She met John McInnes who was studying for an Arts degree during her first year in Dunedin. Their relationship became serious and they married in Auckland at the end of her fifth year. They then moved to Christchurch so John could study at Teacher’s College for a Diploma in High School teaching while Marion did her sixth year at Christchurch hospital. She returned to Dunedin in November 1964 to sit her finals and the graduation ceremony was only a few days later. “I knew before the results came out that my parents had already left Auckland to come down for the graduation. [I was] really worried; what if I don’t pass and they come all this way for nothing.” She did pass and remembers the relief and excitement of processing with her classmates along George Street to the graduation ceremony.

Reflecting back on her time at Medical School Marion said her biggest challenge was “not being able to feel totally comfortable in the medical fraternity …I sort of felt inadequate.” But overall, her time at Medical School was a positive experience

Early Career at Balclutha Hospital

After graduation Marion obtained a position at Balclutha Hospital. Her choice for this was influenced by John’s need to get a teaching position which he did at South Otago High School.

The hospital was a great place to work. It had surgical, medical, and maternity wings and employed two house surgeons. They rotated between the medical and surgical runs swapping every two months. They covered the on-call requirements by working every second night and every second weekend in turn., “There were two full-time consultants living in hospital houses – a surgeon and a physician. And the other medical tasks like anaesthetics were covered by the local GPs. It was a really broad introduction for me to the practice of medicine. Anything and everything came into A&E and you just had to cope.” She also benefited from a huge pay rise that came into action in her first year. Junior doctors had been fighting for a raise for a long time and the year Marion began the pay rose from about £850 a year to about £1,500. “It was like an 80% increase and I was in the first year to get it. We were very, very fortunate.”

While the hospital was an exciting place to work and a very positive first job, she found the transition from student to doctor overwhelming. “The first night I was ever on call someone came into A&E with a Colle’s fracture and I didn’t know how to set a Colle’s fracture. The radiographer said, “Oh, just do an ischemic arm block.” Well, I didn’t know how to do an ischemic arm block. In fact, I hadn’t even heard of an ischaemic arm block. Luckily my offsider (the Senior House Surgeon) was a kind man. He was one year ahead of me and became a great friend……well he did the ischemic arm block for me that night and taught me in the process. This sort of thing happened repeatedly as I had no experience of the every-day practical procedures necessary for the job. I often felt very much at sea and on my own.” However “I quickly acquired many practical skills which was very satisfying and I also learned to manage my anxiety to some degree – this was to do the best I possibly could, leave the situation, and move on.”

After two years in Balclutha Marion and John applied to work with a missionary society called Interserve which placed professional people in countries where their skills were needed.

Working in India

Marion and John moved to North India in 1967, primarily because an international school there needed a teacher of the Commonwealth curriculum for the English, Australian, Canadian, and New Zealand students. Woodstock School was located at seven and a half thousand feet in the foothills of the Himalayas. “We got snow in winter, in December. And it was where the ex-pats went for their summer holidays mid-year to escape the heat of the plains. It was a very pleasant climate.” The couple also had the opportunity to travel during the long school holidays in December and January because the hospital was relatively quiet during winter.

Marion worked at the Landour Community Hospital which primarily served the Indian population in the surrounding hill villages. There were two other doctors on the staff – an American surgeon and an English obstetrician and gynaecologist. At that time the hospital was lacking an anaesthetist and a physician. Marion had known of the anaesthetic need during her last few months at Balclutha hospital and had prepared herself by learning all she could from the GP anaesthetists there. But at her first meeting with Wayne Wertz, the American Superintendent, she was told that she would not only be administering the anaesthetics but she would also be looking after the medical beds. She remembered her first reaction to being told this: “My heart sank, and I thought, “How ever am I going to cope?” I was also informed that the hospital was run on American lines. First thing in the morning there was a ward round and last thing in the evening there was another ward round. They were long, long days.” The medical work was varied and often dramatic such as incredibly low Fe levels secondary to hookworm infestation, the occasional child with Kwashiorkor malnutrition, a young woman of 16 years with her nose brutally chopped off for supposed infidelity.

Aside from the medical work there was one particular area Marion struggled with while in India: “I just hated the gap between the rich and the poor. I was very aware that we paid our cook less than what we spent on our own groceries. And he sent most of it back to his family in the village. I wanted to pay him more, but the other expats said, “No, no, you can’t do that. It’ll upset the whole system.” I hated acquiescing to that system but I felt I had to.”

Re-Training as a General Practitioner

After three years in India, Marion and John moved back to New Zealand. They had recently had their first child and during her pregnancy, Marion developed pre-eclampsia which led to a few weeks on bed rest in the hospital and an emergency caesarean section at 35 weeks. (Luckily a specialist anaesthetist from Ludhiana was holidaying in the hills at that time). The baby was fine, but in the following weeks and months, her blood pressure would not settle. “Eventually I went down to Ludhiana Christian Medical College and Hospital, which was on the plains in the Punjab, and was investigated by a Swiss physician. With medication my blood pressure quickly returned to normal levels. But as soon as I went back up on the hills at 7,500 feet it shot up again. Eventually the medical recommendation was that I should not live at that altitude.”

So they returned to Auckland where John obtained a position at Auckland Grammar School. Two years later, after their second daughter was born, they moved to Wellington for John to become the General Secretary of the Tertiary Students Christian Fellowship of NZ.

When the children reached school age Marion decided it was time to return to work. “I wondered how to get into general practice. I asked our GP – Roger Ridley-Smith was his name – what he would do in my position. He replied, “I’d sit in with a GP and watch what they’re doing.” So I followed his advice and spent some months learning at his practice.” After some time doing locums in her local area, she joined the staff at the Titahi Bay Medical Centre where she worked for the next 30 years.

The position she held there was always part-time. This was extremely important to her even though she had always been told that it was not possible to be a good GP unless you worked full-time. “I was determined I wasn’t going to work full-time. I had two little girls. They came first for me.” So apart from when she filled in for others on holiday, Marion worked four half-days a week. “I chose to work half-days partly to be at home at the end of most school days but also so that I was at the surgery on four days of the week – often enough to have my own patients.”

In the 1980s, to assist with her work in general practice, Marion undertook a two-year course in counselling through the Presbyterian Support Counselling Centre in Wellington. “And that was really helpful. It was based on client-centred non-directional counselling. Listening skills really. I have always thought a really important part of general practice is listening to people and spending enough time with them to go beyond the presenting symptoms when that is appropriate…… I’m afraid I was the sort of GP who was always running late because I spent too long with the patients.”

In 1999 she fulfilled the necessary requirements to be elected as a Fellow of the Royal New Zealand College of General Practitioners (FRNZCGP) and then continued with the Maintenance of Professional Standards Programme until she retired.

Life Outside of Medicine and Retirement

A few years after moving to Ngaio in Wellington Marion and John made the decision to live communally. “It started with an Australian young man and his 3-year-old son. They needed emergency housing which developed into living with us for quite a long time. They just became part of our family. And it was really good. I mean they loved it, and we loved them.” But there were inevitable stresses with shared living in a small house and it became too hard to maintain. They realised that if they wanted to do this sort of thing, they needed the help of others. So they decided to start a more purposeful community. “We decided in consultation with the Anglican vicar and a few friends that we would buy this big, old house, two houses along the road from here … we ended up living there and sharing it with another family, and others lived in the house behind, the house beside and the two flats next door. In all we had 10 adults and 9 children, and we lived communally. We all shared the same philosophy of life. We all belonged to the local Anglican Church. We all wanted to live more simply and we wanted to offer a home to people who for various reasons needed that.” This communal living benefited everyone and they lived this way for 12 years before their individual visions started to differ and the community made the decision to part ways. “However, John and I continued to live there for 8 more years as an extended household. We had a lot of young people live with us and that was really good fun. We had 20 years altogether in that big house and then we moved here [to their current house].”

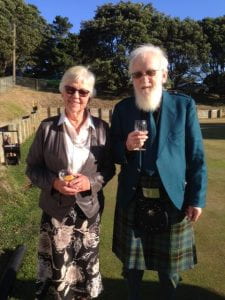

Marion finally retired at the age of 71. This was in response to changes made to the Maintenance of Professional Standards Programme but it was timely. In retirement, she has enjoyed having more time for sport, music, gardening, grandchildren, reading and exploring spirituality. Music has always been an important part of her life and she and John still play in the Ceilidh band they started 30 years ago. Another great love they share is Association Croquet. They consider croquet to be sport’s best kept secret and a highlight of Marion’s life was being chosen to play for the New Zealand team against Australia in the 2011 Trans-Tasman Test Series.

When reflecting on her career Marion said: “I didn’t experience any major barriers in my working life and I have always had really excellent and supportive colleagues I think I was a reasonably good GP in terms of diagnosis and treatment. I’ve listened to thousands of patients over the years and hopefully been a help to most of them. Yes – that decision I made so long ago to follow a medical career was a good choice for me.”