This biography is largely based on the book “Trailblazing Woman” by Judi Davis (nee Washington). Marion was Judi’s mother’s friend and Judi’s childhood doctor and art mentor during her Rabaul years. (1) In addition, the oral histories of their son Helge Grant-Frost and Joyce Steele have been very helpful. (2) Other secondary sources are listed in the bibliography.

1922 Graduate

Contents [hide]

The Early Years

The Early Years

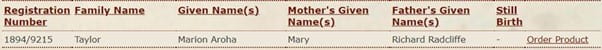

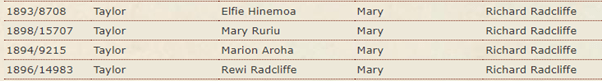

There is some discrepancy around the year that Marion (also nicknamed Matti, Matty, Mat) Aroha Taylor was born. The range goes from 6th August 1891 (1) to 16th August 1898 (4). The New Zealand Birth, Death and Marriage (BDM) Historical Records record her birth as 1894, so for this biography this will be used as the most reliable month and year of Marion’s birth. We will also use Marion when referring to her, although in later life she was mainly referred to as Matti.

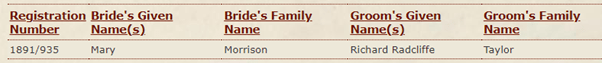

Her mother, Mary Morrison (nee Monaghan), was born around 1858 in Heathcote, Victoria (a town approximately 110 kilometres north of Melbourne). Joyce Steele mentions in her memoirs that Marion’s mother was “very clued up in painting and all sorts of aspects of art”. (2) Her father, Richard Radcliffe Taylor, was originally from Preston, a city in the province of Lancashire, England. He immigrated as a bachelor to New Zealand prior to his marriage to Mary in 1891 at the age of thirty-six years. Mary was thirty-three years of age at the time of their marriage at St Joseph’s Cathedral, Dunedin. Her occupation on their marriage certificate is not recorded but Richard’s is listed as a manufacturer. He was the founder of the Zealander Waterproof Company (1) and died in 1911 at the age of fifty-six years.

Her mother, Mary Morrison (nee Monaghan), was born around 1858 in Heathcote, Victoria (a town approximately 110 kilometres north of Melbourne). Joyce Steele mentions in her memoirs that Marion’s mother was “very clued up in painting and all sorts of aspects of art”. (2) Her father, Richard Radcliffe Taylor, was originally from Preston, a city in the province of Lancashire, England. He immigrated as a bachelor to New Zealand prior to his marriage to Mary in 1891 at the age of thirty-six years. Mary was thirty-three years of age at the time of their marriage at St Joseph’s Cathedral, Dunedin. Her occupation on their marriage certificate is not recorded but Richard’s is listed as a manufacturer. He was the founder of the Zealander Waterproof Company (1) and died in 1911 at the age of fifty-six years.

From the New Zealand BDM Historical Records, we know that Marion had at least three siblings; an elder sister Elfie Hinemoa born in 1893, a younger brother Rewi Radcliffe born in 1896, and a younger sister Mary Ruru born in 1898. With both her parents immigrating to New Zealand, we are unable to establish any Maori ancestral link despite all the children having a registered Maori first or second name.

From the New Zealand BDM Historical Records, we know that Marion had at least three siblings; an elder sister Elfie Hinemoa born in 1893, a younger brother Rewi Radcliffe born in 1896, and a younger sister Mary Ruru born in 1898. With both her parents immigrating to New Zealand, we are unable to establish any Maori ancestral link despite all the children having a registered Maori first or second name.

![]()

The National Archives of Australia have Rewi’s World War I and Marion’s World War II Australian Military Forces Attestation Forms in digital format. (6, 7) They were both born in Dunedin. When enlisting, Rewi was single, living quite close to his mother’s birthplace in the Bendigo, Victoria area and his trade was recorded as farmhand. His mother, living in Roslyn, Dunedin, was listed as his next of kin. In 1941, Marion’s sister “Miss Mary R. Radcliffe-Taylor” was living in Kalgoorlie and was listed as her next of kin.

The National Archives of Australia have Rewi’s World War I and Marion’s World War II Australian Military Forces Attestation Forms in digital format. (6, 7) They were both born in Dunedin. When enlisting, Rewi was single, living quite close to his mother’s birthplace in the Bendigo, Victoria area and his trade was recorded as farmhand. His mother, living in Roslyn, Dunedin, was listed as his next of kin. In 1941, Marion’s sister “Miss Mary R. Radcliffe-Taylor” was living in Kalgoorlie and was listed as her next of kin.

Details of Marion’s primary and secondary schooling are unknown.

Otago Medical School and House Surgeon Years

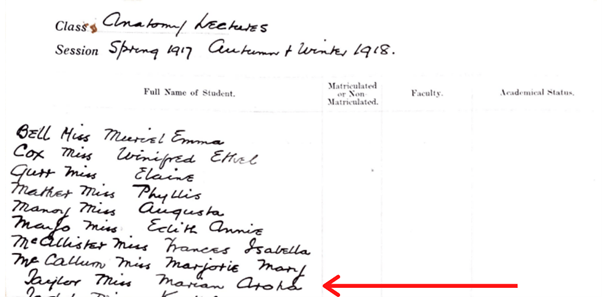

Marion enrolled in the last year to be able to complete the Otago medical course in five years – the structure of which is listed in the “significant information” tab on the website. From 1918, it was six years. The class intake in 1917 comprised 31 students of whom nine were women.

World War 1 conditions gave women more incentive and opportunity to enter medicine, which hitherto was almost entirely a man’s world. Twelve women graduated in 1922, six of whom were from the original class; the starting class did not keep together. Some gave up, usually for health reasons, some dropped back, and some had begun the course earlier than Marion but had repeated a year or two for various reasons. (8) Marion graduated with her Bachelor of Medicine and Bachelor of Surgery (MB ChB) in 1922, at the age of twenty-seven. She officially changed her surname to Radcliffe-Taylor in 1922 (9) and thus graduated with this surname. (Radcliffe was her father’s middle Christian name.)

In 1922 she was appointed junior resident house physician at Dunedin Hospital and the following year was senior resident house surgeon. (10) During this time she was very fortunate to work with a fine orthopaedic surgeon. This experience allowed her to discover very early on “what her niche would be in the specialised medical world”. (11)

Early Career

In 1924, Marion was employed as resident in charge of the Orthopaedic Department of Dunedin Hospital during the absence of the orthopaedic surgeon in America. The following year, she was medical superintendent of the Grey River Hospital, Greymouth for three months and later in the year was appointed surgeon in charge of poliomyelitis cases at Dunedin Hospital. In 1926 she was in general practice in Dunedin before commencing an orthopaedic surgery practice in 1927 and 1928 with Dr J. Renfrew White, an honorary orthopaedic surgeon at Dunedin Hospital. (10)

She spent 1929 and 1930 in Great Britain and various capitals of Europe doing post-graduate work in industrial and orthopaedic surgery. While in Great Britain, she spent three months on the resident staff of the Shropshire Orthopaedic Hospital in Oswestry located near the border of Wales. During this time, she obtained her Fellowship of the Royal College of Surgeons (Edinburgh). (10) A. Millar reports the reason Marion gave for going to Edinburgh was that women were not allowed to attend the lectures in London. (12)

She returned to New Zealand and spent 1931 in her previous orthopaedic surgery practice in Dunedin. (10) Marion may have been the first woman orthopaedic surgeon in New Zealand. This was unable to be confirmed by the New Zealand Orthopaedic Association as they only started a training programme in 1973. Prior to this surgeons were trained in General Surgery and then, like Marion, went overseas to do Orthopaedic Fellowships.

Australian Career

In 1932 she became aware that there were no orthopaedic surgeons in Perth, Australia, so she demonstrated her adventurous spirit and moved there. (11) In later life, it is also reported that on her return from England, she realized she had had enough of the New Zealand climate, so set out for Western Australia (WA). (12) She became the assistant orthopaedic surgeon at Perth Hospital and the surgeon in charge of the Orthopaedic Department at Fremantle Hospital. She also spent a year as acting orthopaedic surgeon at the Children’s Hospital during the absence of the orthopaedic surgeon-in-charge. (10)

Joyce Steele was one of the first two women elected to the South Australian Parliament in 1959. She was born and educated in Perth and one of her early secretarial jobs was with Marion. In her oral history transcript held at the Mortlock Library of South Australia, she describes her three-year employment with Marion who remained a life-long friend: (2)

At the interview for the position her impression was that Marion had Maori blood in her; she was a fine-looking woman but terribly mannish. She always wore suits with ties. She had to wait an hour to be interviewed – until Marion saw all her patients. She then sat down in a lounge chair with her foot over the chair and lit a cigarette and just looked at her until it became embarrassing. Joyce did not say a thing. Finally, Marion said “What I want of course is a wife”. She wanted someone to look after her. She didn’t have time to do the things she ought to do. She needed a wardrobe, someone to see she had sufficient clothes, to go through her wardrobe and then buy the necessary clothing for her, to make appointments for the hairdresser and for servicing her car.

One of the first things Joyce did was to find her new clinic rooms – a professional suite which was very well set up and included a separate plaster room. Joyce then organized the purchase of a house for her and then had to furnish it. Marion had beautiful large pieces of oak furniture in storage which she had brought back from Edinburgh. Marion trusted Joyce to “just get it furnished”. She had a wonderful time going to the auctions and getting appropriate antique pieces to go with the Edinburgh pieces. Joyce was only twenty-three, but they established a good rapport and Marion would do everything she’d tell her to do.

Joyce recounts that she had a beautiful yacht on the Swan River which she skippered herself. She was a marvellous angler and used to go off with teams of men on fishing trips. She was hopeless with men unless it was a professional relationship.

On the 27th October 1938, the Executive Council of the WA Legislative Assembly approved the appointment of Marion as the next medical officer of the State Insurance Office. (10) There was strong criticism to her appointment. A deputation from the Perth Council of the Australian Labour Federation was sent to the Minister of Labour protesting that practically all persons who would be examined by Dr Radcliffe-Taylor, if appointed, would be men. The government felt that any prejudice on account of her sex would quickly disappear and that they could not justify an appointment of a person whose qualifications were in no way comparable. Marion had been outstanding among the applicants due to her exceptional qualifications. In addition, in her previous work, she had examined and treated many men which she would also be doing in this role. (13) According to Joyce Steele’s recollections, she flew her own planes around WA during this time when she was investigating compensation cases. (2)

One legacy she left during her time as State Insurance Officer was devising a boot with a steel cap to be worn by the miners so accidents would be less likely to occur. Marion had made a survey of injuries to the big toe in the gold mines at Kalgoorlie, WA. These injuries left an on-going damaging effect for walking and often produced arthritis and a rigid toe.

During World War II, Marion was listed as a Captain of the Australian Forces List (Service No. 56564) from 1940 to 1943. (4)

Marriage and Family

In 1945, at around the age of fifty, Marion married Charles Ray Grant-Frost (known as Ray), aged thirty. It is not known how they met. He was born in Taumarunui, New Zealand in August 1915 and had served in the Royal Australian Air Force during World War II (Service No: 405791). He was a prominent wheat and sheep farmer in the Beverley, WA region, which was 150 kilometres from Perth. Marion moved to the area to be with him and set up private practice in Beverley as well as in the nearby town of Brookton which was 33 kilometres away. She delivered many babies as part of her practice and was often thanked in the Beverley Times birth notices. (1)

Meanwhile in 1949, a Latvian refugee family arrived in Fremantle, WA from Riga, the capital of Latvia via the port of Naples, Italy. The father was a well-known artist (painter and cartoonist) who criticised the Soviet government through his cartoons and articles. This resulted in them having to flee to Germany and eventually they arrived in Australia as refugees. The family consisted of Siegrid, her second husband Werner Linde, their own son Werner Jnr, Siegrid’s two sons Dieter and Helge from her first marriage, and Werner’s son Gert from his first marriage. (14)

Marian, in the meantime, heard about this amazing artist immigrating to Fremantle, and convinced the federal authorities to allow the family to come to Deep Pool, Ray and Marian’s property at Beverley, WA. The reason permission was granted by the authorities, was that Gert Linde was a strong lad and would make a good farm worker. (14)

The move of the family to Beverley resulted in Dieter and Helge eventually being adopted by Marion and Ray as their own sons and their surnames were changed to Grant-Frost. The rest of the Linde family moved to Adelaide. (14)

In the hot January school holidays of 1950, Dieter and Helge were squeezed into a little Austin A40, along with Marion, Ray, and artist Elise Blumann’s son Niels. All those people plus their luggage in such a small car was memorable for Helge. Off they drove to Adelaide from Perth to visit the boys’ birth mother. The trip was hot, dusty, cramped and a very long way, especially in those days. First, they went to Adelaide to visit Siegrid who spoke limited English and then they continued to Melbourne. Their adopted parents probably thought it was a good way to show the boys the real Australian world. After this, the two boys had limited contact with their birth mother due to the geographical distance and getting established in their own future endeavours. (14)

Joyce Steele recounts how Dieter and Helge were brilliant students and had charming manners, which Marion and Ray had taught them. (2) They received the best education in Perth and were high achievers. They both attended Scotch College in Perth as boarders. Dieter attended St George College and Helge went there for a year before moving to Sydney for veterinary studies. Helge joined his first Veterinary practice in Singleton, New South Wales, and later had the government position as District Veterinarian for Central New South Wales in an advisory, non-clinical role, dealing with cattle and sheep production. Dieter worked for the chemical company Bayer. Their step-brother, Werner Linde (Jnr), became a doctor in Adelaide where he also achieved double Olympic basketball fame and was inducted into the South Australian Basketball Hall of Fame in 2020. (14)

Marion also cared for her niece Trudy, who had muscular dystrophy, and communicated with health professionals around the world seeking help for her. (2) In written communication from Helge, he reports how Marion spent a lot of time and energy researching and trying to find a cure for the muscular dystrophy that her niece Trudy, who was a nurse in WA, was afflicted with. Helge and Dieter were asked by Marion to take care of Trudy when she died. However, that didn’t happen as Trudy died first in 1971. (14)

Towards the end of 1949, the Beverley property was sold and a property at Boyup Brook was acquired; a town approximately 160 kilometres south-east of Perth. Marion retired from medical practice to become a farmer with Ray.

The family suffered severe financial problems in the mid-1950s due to the wool clip being significantly devalued following the ceasefire of the Korean war in 1953. Prior to that, Australia and New Zealand were said to be “riding on the sheep’s back”. In addition, a bushfire gutted the entire Boyup Brook property and restocking at record high prices left them in desperate financial straits. They decided that Marion needed to return to medical practice. Despite Marion’s efforts, the Boyup Brook property was eventually sold to a neighbour. (1)

The Rabaul, Territory of Papua New Guinea Years

Following the war, the Australian government was involved in an administration union with the Territory of Papua New Guinea and attracted skilled people to the country through income tax incentives. (15) According to the recollection of her friend Judi Davis, Marion moved here in the late 1950s and set up a private medical practice in Rabaul, a township in one of the smaller islands of Papua New Guinea, to assist with the family finances. (1) Another version is that she was an ardent feminist and became incensed at not receiving equal pay for equal work so she resigned from the government administration and moved to Rabaul. (12) Joyce Steele recollected the main reason she moved first to Port Moresby and then on to Rabaul was for respiratory health reasons. Even during her early years in Perth, while working for Marion, she recalled that she suffered from respiratory problems. (2)

Marion and Ray mostly went their separate ways around this time but there is a record of him visiting her in Rabaul. At this time there was talk of them buying a nearby plantation but this never eventuated. (16) Their adopted son, Helge, recounts that even though they were worlds apart in her New Guinea days, Marion did not actually divorce Ray Grant-Frost and used both her surnames depending on her professional circumstances. Helge enlisted in a university cadetship in 1960 and went to New Guinea as a veterinary officer. He was based firstly at Port Moresby and then Lae and Goroka. He was able to visit and spend some time with Marion in Rabaul during this time. The whole family rarely saw each other because of living long distances apart. However, letters were written, and they came together in Tasmania in 1962, when Dieter married. (14)

Joyce Steele recollected that when Marion left her husband to go to New Guinea, he started to sell off all her beautiful works of art, her fine furniture and finally the farm itself. Marion was not given any of the money from these sales. She notes that Marion had some magnificent pictures in the home. (2) However, Helge felt that when their property in Western Australia was sold, there wouldn’t have been much money left after debt repayments. Ray went to the Kimberleys, the northernmost region of WA. Possibly because there were some family friends on a property in that area. He made friends in the town of Derby, lived in a simple house, and drove taxis for a living. When he became very ill, Ray was taken south to Perth and died in the Fremantle Hospital. Helge and his wife Sue rushed over there in time to bury him. Ray’s death notice is recorded in the November 13, 1985 issue of the Sydney Morning Herald. Marion is not mentioned – only his two adopted sons, their wives and children. (14, 17)

Joyce Steele went up to visit Marion at Rabaul circa 1960 and observed that Marion was absolutely revered all over the islands as she used her skills as an orthopaedic surgeon to correct many of their deformities. She consulted to the government administration and went throughout New Guinea operating and advising. Although she was eccentric, she was able to relate to the indigenous peoples on a very human level and lived there until the early 1970s. (2) She had a practice in Rabaul for more than twenty years.

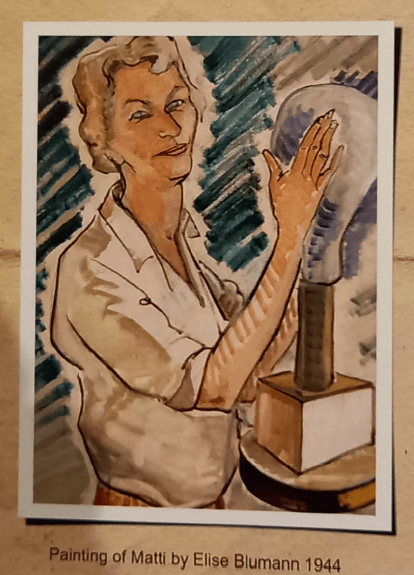

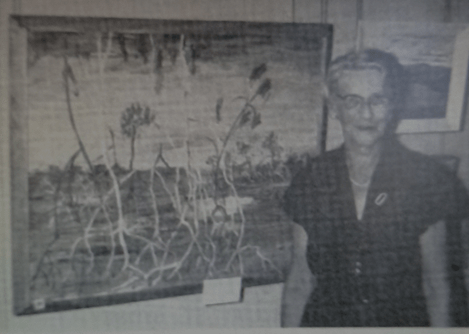

The Artist

Marion was not only a brilliant doctor, but also a talented, self-taught artist – particularly as a sculpturer but she also did some etching and oil painting. She and the modernist West Australian artist Elise Blumann (Burleigh) were friends who worked and exhibited together, and went on painting trips into the West Australian outback. (1) They had an exhibition in Perth in 1944 called “Modern Works of Art, An Unusual Exhibition”. (18)

Marion was not only a brilliant doctor, but also a talented, self-taught artist – particularly as a sculpturer but she also did some etching and oil painting. She and the modernist West Australian artist Elise Blumann (Burleigh) were friends who worked and exhibited together, and went on painting trips into the West Australian outback. (1) They had an exhibition in Perth in 1944 called “Modern Works of Art, An Unusual Exhibition”. (18)

Marion helped start a local sketching club in Rabaul and was an active member of the Rabaul Art Society. It is alleged that she spent time in Greenwich Village, New York City taking art lessons and won a coveted Salmagundi Club Scholarship (12) but this could not be verified by the Salmagundi Club in 2021.

Retirement

Marion loved to travel and was very interested in the mysteries of the moon and Mars. If she had had the chance, she would have loved to have travelled there. She retired to Caloundra on the Sunshine Coast of Queensland in 1974 at the age of eighty. On March 11, 1976, whilst visiting a friend in Sydney, she suffered a major heart attack and died suddenly. She was cremated at the Albany Creek Crematorium, Brisbane. (1) Helge recounts that sadly he and Dieter were not notified of Marion’s death at the time and only found out later from Pat Green, an ex-Rabaul friend and the executor of her will. (14)

Her good friend and artist Judi Davis sums up “her Matti” in this way: (1)

Finding the right words to describe Matti is difficult because there are too many. She was very kind, but a little intimidating to me as a child. However, the first description to come to mind is eccentric – nicely eccentric. This was part of her creative artistic side. But she was scientific too. Matti was a doctor long before it was acceptable for a woman to be one; a brilliant Orthopaedic Surgeon and General Practitioner by all accounts …. It is impossible to know how many lives she saved and improved, and how many babies she delivered into the world .…. I think Matti was an extraordinary person. A trailblazing intrepid feminist and a woman who was well before her time in many ways. Matti lived life to the full and was interested in everything it had to offer. I am honoured that she has been part of my life.

Bibliography

- Davis J. Trailblazing Woman. Judi Davis; 2019.

- Steele J. Recordings of Joyce Steele [sound recording] Interviewer: Meg Denton Adelaide, South Australia: State Library, South Australia; 1990; [Oral History, Number 368/1]. Available from: https://www.catalog.slsa.sa.gov.au:443/record=b2178666~S1

- Territories Talk-Talk – p51 Sydney: Pacific Islands Monthly; 1963. Available from: https://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-324690885/

- Smith A. Radcliffe-Taylor, Marion Aroha (1898 -1976 ): Encyclopedia of Australian Science 2015; 2003 [updated 1.8.2007; cited 2021 27.7.2021]. Available from: http://www.eoas.info/biogs/P004423b.htm

- Births DaMR. New Zealand Marriage Certificate [Internet]. Wellington: Births, Deaths and Marriages Registry; 2021.

- Rewi Radcliffe Taylor, Service No. 921: Australian Government; National Archives of Australia; B2455. Available from: https://recordsearch.naa.gov.au/

- Marion Aroha Radcliffe-Taylor; Service No. W56564: National Archives of Australia; Australia Government. Available from: https://recordsearch.naa.gov.au/

- Preston FI. Lady Doctor – Vintage Model. Wellington: A. H. & A. W. Reed Ltd.; 1974.

- Papers Past. Otago Daily Times. 1922 09.03.1922.

- State Insurance Doctor Perth: The Western Australian; 1938 [cited 2021 30.7.2021]. Available from: https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/page/3719214

- March M. With Notebook and Pencil Adelaide, South Australia: The Advertiser; 1938. Available from: https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/page/2612951

- Millar A. A Life Full of Friends Port Moresby, Papua New Guinea: Papua New Guinea Post-Courier; 1970. Available from: https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/250189204

- Women Doctors. Triumph in W.A. Townsville, Queensland: Townsville Daily Bulletin; 1938. Available from: https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/page/5551768

- Grant-Frost H, Davis J. Remembrances of Matti and Ray by Helge Grant-Frost. Forthcoming 2021.

- Wikepedia. States and territories of Australia: Wikipedia; [updated 27.08.2021]. Available from: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/States_and_territories_of_Australia

- Hilder B. A Brett Hilder Profile: Mixes Medicine with Paint. Pacific Islands Monthly 1960.

- Obituary: Grant-Frost, Charles Ray. The Sydney Morning Herald [Obituary: ]. 1985 13/11/1985. Available from: https://www.newspapers.com/newspage/126157873/

- Morison GP. Modern Works of Art, An Unusual Exhibition: The West Australian 1944 [14.08.1944]. Available from: https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/44819300