This biography is based on an interview with Nigel Wilson (Judy’s son) in May 2021 for the Early Medical Women of New Zealand Project. Further information and photographs were sourced from “Carry On: A Biography of John Wilson”, written by Michael Kelly. The interviewers were Cindy Farquhar and Michaela Selway.

1947 GRADUATE

Contents [hide]

Family History and Life on the Farm in the Wairarapa

Judy Ann David Collins was born on August 6 1923, the youngest daughter and the third of five children to David and Sybil Collins [1, p.65]. David had grown up in the Wellington area and was educated at Wellington College and Trinity College, Cambridge, “where he gained blues in cricket and rowing. An outstanding all-round sportsman, he was a fine tennis, rugby and polo player and golfer. He studied medicine and was nearing the end of his time at university when he contracted meningitis. After he recovered, doctors suggested that he find an occupation that would take him outside” [1, p.66]. He decided upon farming. His original dream was influenced by his father, Judy’s grandfather – Dr William Edward Collins. William had served as the chief medical officer on the hospital ships in Gallipoli and other campaigns during World War 1. He continued to practise medicine in New Zealand outside of the war and volunteered for various other organisations, such as the Military Pensions Board. He was twice president of the Wellington Club, helped to establish the Wellington Golf Club, served on the Senate of the New Zealand University, the Legislative Council in 1914, was thrice elected the chairman of the New Zealand branch of the British Medical Association, and in 1932 he was elected the first president of the New Zealand Red Cross [1, p.65]. Judy’s decision to pursue a medical career was also influenced by Dr W. E. Collins, her grandfather [2].

Schooling

Judy and Joe were initially educated by governesses, “but they were next to useless and we made short work of disposing of them by digging traps in the garden; Joe even took a potshot at one of them with a Beebee gun. She understandably resigned with our punishment being sent to the local state school at Kahutara.” [1, p.160] Judy attended Kahutara School for two years. She rode her Shetland pony bareback to travel to school [1, p.160]. After two years at Kahutara, at the age of 11 [1, p.67], she transferred to St Matthew’s School in Masterton for another two years. Here, she was a weekly border [1, p.164].

For secondary school, she was sent to Woodford House in Havelock North. Upon arrival, Judy had to sit an intelligence test that determined which class she would be enrolled in. She was slightly disappointed to find out she was put in the grade above her age group, which meant that she felt socially out of her depth for the four years. Despite this, it gave her the time to focus on her interests: “[I] just did my own thing, worked hard, and enjoyed all the sports. For five years I had piano lessons, and was rostered to play the organ for the chapel services. Looking back I realise that I played deadly dull voluntaries as there was no help or suggestions from the music teacher and no orchestra or band in the school, such a contrast to today’s school music scene.” [1, p.164]. She felt like the atmosphere and structure at Woodford House kept them all very cloistered. Looking back, she was very “naive and socially inept” when she left school [1, p.164].

“I think it was during my fourth and fifth year that I thought about a medical career, but hadn’t taken mathematics or Latin since third form. Matric in both was a requirement for entry into Medical School. Tuition was arranged, and I was excused from dressmaking. The Headmistress, Miss Holland, ex Wycombe Abbey, was an outstanding Head. She interviewed all leavers. I was quite surprised when she said to me, “I suppose you will go on with your music?” “No Miss Holland, I am going to be a doctor!” Two others did exactly the same thing and we three and also a girl from Nga Tawa all graduated in the medical class of 1947, and have met up at medical class reunions ever since.” [1, p.164]. Her son, Nigel, recalls her saying that she picked up Mathematics and Latin relatively easily [2].

The Delayed Start to Medical School

In the summer before Judy was to start Medical Intermediate, she suffered an accident. It was January of 1940, her first summer holiday after finishing school, and a group of her friends decided to spend the holidays at her parent’s beach house at Paekakariki: “This was to acclimatise ourselves, to some extent, to the world at large.” [2]. She was walking along The Parade with one of her friends when she was hit by a car and left with a fractured skull, partial deafness in one ear and tinnitus, the last two of which lasted for the rest of her life. She spent three weeks in the hospital recuperating before she was sent back to convalesce at home on her parent’s farm [1, pp.68, 164-5].

The accident caused her to miss the early 1940 intake for Medical Intermediate at Victoria College of Wellington, and she ended up spending the majority of her time at home. This was difficult for one who had been so active growing up. Nigel said that Judy was “bored to tears and drove [her] parents to distraction” [2]. After pestering them for much of the year, Judy’s parents eventually gave her permission to enter the final term of 1940, where she would read Mathematics and sit one Botany examination in preparation for Medical Intermediate the following year [1, p.69].

During her Medical Intermediate year, Judy boarded in Seatoun with the wife of a vicar who was overseas for the war. From Seatoun, she was able to catch the tram and then cable car to town for her classes [1, p.165]. She achieved well during the year and was accepted into the Otago Medical School for the 1942 intake. Her delayed intake ended up being a blessing in disguise.

“In some ways the accident was a blessing in disguise as the delay in starting first year medical school in Dunedin found me with a great group of men and women. We have been friends for life, reflected by the frequent medical reunions we have enjoyed. We spent five years together in Dunedin. They were war years, with food rationing, night blackouts, restricted travel, restricted campus activities, army training camps, etc. So I suppose we became bonded especially as the majority lived in hostels, Knox College, St Margaret’s, where I lived, Selwyn College, etc.” [1, p.165; 2]

Otago Medical School

Regarding her classes, Judy enjoyed anatomy the most. She never spoke about being discriminated against as a woman, but “mum was tough, as I said, growing up on a farm as the 3rd daughter. Men would’ve quickly worked out she would stand up for herself” [2]. For her final year, Judy returned to Wellington and was offered live-in accommodation at Wellington Hospital, which was only offered to the highest achieving students [1, pp.69, 165]. The medical students were given the option to return to Dunedin if they wished to be capped with their class, or they could be capped with the Victoria University College students. Very few accepted either option, and Judy was not one of them. Nevertheless, she graduated in 1947 along with 12 other women students.

House Surgeon Years and Marrying John

Following her graduation, Judy was offered a House Surgeon’s position at Wellington Hospital, first in the Eye, Ear, Nose and Throat department, and then in casualty. “It was an eye opener and great training, especially on a Friday night, when patients arrived in with fish bones in their throat or bleeding gums following extraction of teeth.” [1, p.165].

Following her time at Wellington Hospital, Judy completed her House Surgeon years at Silverstream Hospital, Upper Hutt. Silverstream had been built by the American Marines during the war years to treat their casualty patients from the Pacific [1, pp.69, 166]. The Wellington Hospital Board took over Silverstream following the conclusion of the war, and from then it specialised in “long term orthopaedic patients, chronically ill elderly, a children’s ward for children with chronic tuberculosis (TB) infections and poliomyelitis during the epidemic. The hospital was complete with a medical superintendent, an elderly medical registrar known to us all as ‘Auntie,’ four house surgeons, nursing staff, physiotherapists, and dieticians, plus a swimming pool and tennis courts. Later the large kitchen cooked the ‘meals on wheels for distribution.” [1, p.166]. Judy wrote that the TB was an “occupational hazard” as many of the staff contracted it while working there. Despite that risk, she loved working at Silverstream because it was easy to travel to by train, it was located in a beautiful spot along the Hutt River that had the sun on it all day, and it was a slower pace than Wellington Hospital, which gave her time to ‘recuperate’ [1, p.166].

“His father, he came from Westport. And his father had read about law. So the mayor comes along to him, this being about 1880, and says to him, “Wilson, you know more about law than anyone else in the town. I hereby appoint you the town lawyer.” In time, John was sent by his father to Canterbury University to study law formally. John came back to Westport and said to his father, “Right, now can we set up in law together ?”. But then his father said, “No. This is a one-lawyer town. Find your own town.” So he went to Wellington, and by chance, his first job was in Featherston.” [2]

Though they spent much time together, “Judy was not entirely certain of John’s intentions as he ‘had his eye on other women at the time’.” [1, p.69]. Everything changed in the 1948 Nomads Tournament:

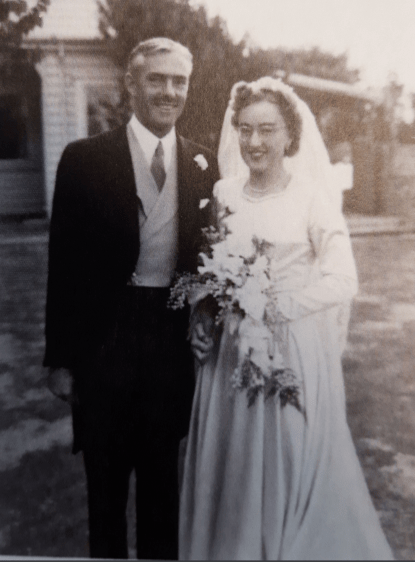

“The 1948 Nomads tournament at Paraparaumu Beach, the first such event after the war, was an important episode in the couple’s lives. John, a last-minute replacement in the field, was invited by Judy’s parents to stay at the Paekakariki beach house … John played Judy in a foursomes match and on the 18th she produced a particularly good shot to the green. That so impressed John that he said to himself ,’ She’ll do me’. When John proposed to Judy at the family farm, she turned him down. She still felt uncertain, but deep down knew that she was going to say yes eventually. John must have had a strong feeling that she would relent because he arranged to play golf with his future father-in-law David Collins (D.C). at Heretaunga before going up to Te Kopura for dinner. He planned to use the opportunity to seek his permission to marry Judy, as was still the custom in those days. For his part, the shrewd D.C. had a pretty good idea what John was up to. After dinner, John asked D.C. for help fixing something with his car and the two of them spent the next half hour peering into the engine. Back in the house, Sybil was ‘getting more and more restless’, as, to her mind, John was not ‘getting on with it’. Her device to move things along was to toss a couple of hot-water bottles out the window at the two men. John took the hint and immediately asked D.C. if he could marry Judy. D.C. said yes and went straight inside to ring the Bidwells to invite them over for champagne. Soon the Collins and Bidwells were toasting the happy couple.” [1, p.69]

Judy started a new medical job at Wellington Hospital at the beginning of 1949. However, she quit after a few months, as the couple were getting married in March and her mother had been diagnosed with cancer [1, p.166]. They were married on March 12, 1949, and it was a beautiful day for a wedding. One of the farmhands on her father’s property drove Judy and her father “in his polished beyond belief Chrysler car (the same model as Dad’s) … As benefits such a solemn occasion, George was driving at a very sedate pace but as we reached the Tauherenikau River bridge Dad asked George the time; ‘2 o’clock, sir!’ ‘That’s our ETA, so step on it, George’, yelled Dad. We were swung around corners at high speed (no seat belt in those days) and with brakes full on we came to a gravel-scattering stop just outside the church!” [1, p.161].

The reception was then held at the Collins’ family farm. The weather was perfect (there was no wind, and all they had was an awning attached to the house to provide shade for the tables. The couple then went on a two-week honeymoon around the North Island, visiting places Judy had never been to before, such as Rotorua, Ohope Beach, Mount Maunganui and Auckland [1, pp.70, 167]. Upon their return, they moved into John’s flat in Rawhiti Terrace, and Judy found work in the Health Department as a school doctor, a position she held for only a few months [1, pp.71, 166, 167].

The Intermediary Family Years

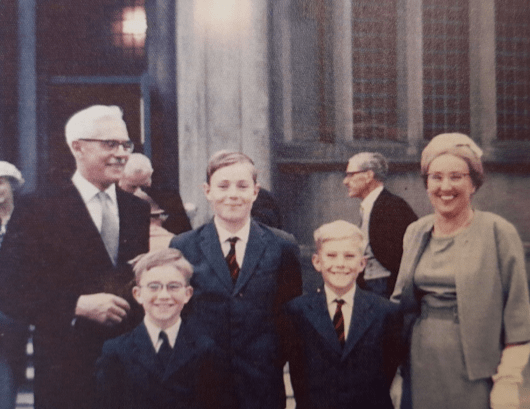

Nigel mentioned that his father was very much a product of the times; he was relatively conservative and did not believe that Judy should work while raising children. “So she stopped work. She did something there, but not much” [2]. She did not even mention to her children that she was a doctor. “I was probably 10 or 11, and I went out to the letter box, and I said, “Mum. There’s a letter for Dr. Judy Wilson. Who’s that?” She said, “That’s me. I’m a doctor” [2]. Even though the children did not know that Judy was a doctor, the rest of the community certainly did: “The local community knew about it because people would arrive to say, “What do you think about this Judy?” And they’d have a child with a rash or something. I remember one kid had choked and she came rushing in and Mum whacked her on the back and the kid went from blue to normal” [2].

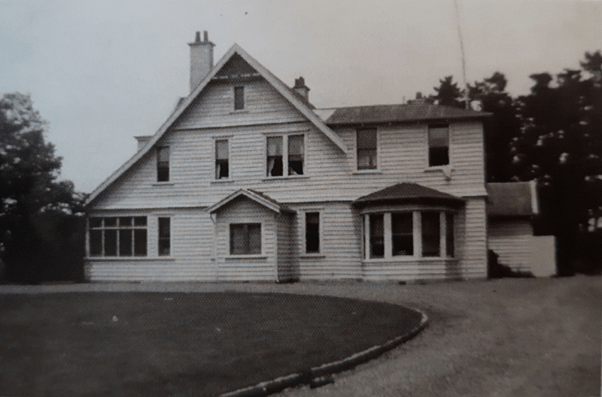

Not long after they got married, John and Judy found a house in Upper Watt Street that they could buy. It was on a hill, and one could only access it via many steep steps, a bridge over Lennel Road and then a zig-zag path. Despite the poor access, it had a beautiful view over the harbour, though it got no sun during winter [1, pp.71, 167]. They did not stay in this house for too long, though. Their first son, Rupert, was born on August 14 1951, and they decided to sell because “one cannot live on a view” [1, p.167]. The Wilson family also wanted to be close to family and friends. Returning to Silverstream was proving to be a good idea, as this would mean they could also return to their beloved golf club, and Judy had enjoyed her work as a doctor in this area [1, p.71].

“Civil servant Bill Barr and his wife Grace, who lived at 1 Chatsworth Road, Silverstream, heard from John’s sister Bettie that the Upper Watt Street house was on the market. They were keen to move because they were finding their rates too high. Grace Barr turned up one afternoon to look through the Wilsons’ house and then suggested to Judy that she and John visit them the following weekend. John was immediately sold on the house, but Judy wasn’t so sure. The narrow windows and the Barr’s oak furniture made it seem dark, a significant contrast with her family home in Te Kopura. However, she was soon won over and, in an extraordinary piece of bartering, the Wilsons and Barrs agreed terms and exchanged houses on the same day” [1, pp.72-73].

Both Hamish and Nigel were to follow Judy and pursued medical careers. Hamish became a general practitioner, then taught at the Otago Medical School. He co-authored a book on medical practice and in time became an Associate Professor of the University. Nigel became a children’s heart specialist in Auckland and became an Honorary Associate Professor (University of Auckland) for his clinical research, especially in rheumatic heart disease. Rupert proudly followed his father John, becoming a lawyer. He specialized in commercial law, becoming a managing partner of the large Wellington and Auckland law firm, Chapman Tripp

During her pregnancies, Judy got the idea to foster unmarried pregnant women for the duration of their pregnancies, a common occurrence for women doctors in this period. Having them in the house meant that she could support them, and in return, they could help her with the children and housework. One of the four women they fostered (Jean) became so close to the family that they all remained in contact for the rest of their lives [1, p.123].

Returning to Work

In 1965 with all of her boys now in boarding school, Judy decided to return to part-time work. She once again found work with the Health Department in Upper Hutt. She first started in the Plunket Clinics but soon expanded out to working with the Public Health nurses in schools, IHC, and various kindergartens [1, pp.128, 174]. “Our philosophy was to support and reassure the often stressed and tired mothers. As a result of these checks there was early detection of heart, hearing, visual, orthopaedic and other defects which were then referred to the family GP or specialist. On one occasion, the Plunket nurse and I diagnosed congenitally dislocated hips in a three-year-old under treatment by a chiropractor; this is a condition in which early detection is vital” [1, p.174].

Judy came across many issues in child health that they had to convince the Plunket nurses needed addressing. For example, she argued that the majority of the infant cot deaths “were a result of tiredness, travel, and respiratory infections resulting in suffocation when babies were put down to sleep on their tummies” [1, p.175]. She based this on four specific, sudden, cot deaths that she had inspected. “And so she talked with the mothers and supported them the best she could, and she made a lot of notes, and she presented at the local Hospital. I think it was either Hutt Hospital or Upper Heart Medical Centre, and a paediatrician present was Rodney Ford, [who] was most disparaging of Judy’s observations. Some years later Dr Ford was a co-author of the landmark New Zealand study led by Professor Ed Mitchell that found that babies sleeping on their tummy was indeed a risk factor for cot death. Surmise what you will” [2] On another occasion, Judy and a Plunket Nurse visited the Head Office of Hannahs when pointed shoes became children’s fashion, which were “rigid and too tight” [1, p.175]. As a part of her role, Judy was requested to conduct a survey on children’s obesity and found that “the children who went to school with no breakfast were often the obese ones” [1, p.175]. During this part of her career, she worked in passing with Dame Cecily Pickerill, doing referrals for cleft lips and palates.

Volunteering for the Red Cross

Alongside returning to work, Judy desired to make a voluntary contribution. Judy followed in her grandfather’s footsteps by signing up to volunteer for the Red Cross. Nigel “can remember the day we collected for them when I was nine years old, and Mum said, “That was a complete shambles. We’ll get on the committee.” And so within a year, she was on the committee” for the Upper Hutt Branch [2]. “Judy attended monthly meetings, gave tuition and took oral and practical examinations in first aid. She became involved in recruiting volunteers, fundraising, meals on wheels and many other activities” [1, p.114]. Judy offered free preschool babysitting to tired, stressed mothers to give them a morning break, and in 1976 she assisted the relief team for the massive flooding that occurred in the Hutt Valley. “The Upper Hutt Red Cross emergency unit was called out in the early hours to rescue trapped victims.” She arranged a welfare caravan and for the collection and distribution of food and relief money. Judy was twice a branch president and a patron from 2008 to 2011 [1, p.175]. She later was awarded a life membership.

“My greatest achievement was enlisting John as president. By 1981 he was elected President of the New Zealand Red Cross Society and later became Councillor of Honour, I accompanied him to overseas meetings of the society” [1, p.175]

Life Outside of Medicine

They were both Christians and retained a close affiliation to the church their whole lives. They had come from Anglican backgrounds and were strong supporters of St Mary’s in Silverstream, where they held all of their important family events, such as marriages, funerals and Christmas services. John was also an occasional vestryman at St John’s in Trentham [1, p.127].

In 2011, Judy fell out of bed and broke her hip. Her health gradually deteriorated, but as she was adamant about not going into a rest home, her sons and health carers helped her to stay on in the family home in Silverstream. On January 7 2016, she passed away peacefully.

Judy was a female medical graduate in the historically challenging 1940s. Her main strength was her capacity to engage and connect with almost everyone she met. She juggled a part-time medical career with raising an energetic family, as well as having a very wide range of interests, including community work, sport and travel. She made a significant contribution to the post-war rebuilding of New Zealand society.

Bibliography

[1] Kelly, Michael, and Wilson Family. 2012. Carry On: A Biography of John Wilson. Wellington, N.Z.: Wilson Family.

[2] Wilson, Nigel. May 18 2021. Interview with Nigel Wilson. Interview by Cindy Farquhar and Michaela Selway. Collection: Early Medical Women of New Zealand.