This biography is based on multiple interviews with Alice’s family members. The interviews with Anne Hanna (nee Morris), Graham Mandeno, John Hughlings Jackson, Alice Walker, and Mary Daphne (Bobbie) Woodward were conducted by Zana Bell for the Alice Horsley Project in 2002 and accessed in 2021 at the National Library. Cindy Farquhar and Michaela Selway conducted another interview with Anne Hanna in February 2021 for the Early Medical Women of New Zealand Project. Further resources are listed in the bibliography.

1900 GRADUATE

Contents [hide]

Family History & the Move to New Zealand

Alice Woodward was born on 3 February 1871, the firstborn child of William and Laura Woodward [1]. William and Laura both originated from England. William was born in 1824 in Marston Sicca, Gloucestershire [2, p.32]. His mother passed away when William was quite young and his father remarried shortly afterwards [2, p.32]. William was financially cut off not long after the remarriage; allegedly, the new wife shifted the full inheritance to her own son [3]. Nevertheless, William received a proper education and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts Honours Degree from Trinity College, Cambridge, where he gained “the coveted triple blue” in rowing, running, and swimming [2, p.33; 4, p.8].[1] Following his studies until the time he met Laura, William’s known occupations were “collecting rents from an Irish estate for an English nobleman, buying horses in Ireland for the same man and procuring remounts for the Indian army” [2, p32]. His employers specifically sent him to buy horses, primarily in Ireland, as he was good at predicting how they would turn out [5].

Alice’s mother, Laura, was the youngest child of two daughters and was born on 2 April in either 1845 or 1848. The two girls were orphaned quite young when their parents “sailed for Australia, with thousands of other hopeful prospectors, in the early days of the Ballarat gold rushes, which lasted from 1851 to 1857” [2, p.33]. It is believed that her parents were killed in the gold rush riots, but they were never heard from again and there is no paper trace from this time to confirm what might have happened [3; 4, p.8; 6]. Nevertheless, the two girls were left in the care of a rich uncle who cared for them very well. He sent them to a Quaker school in London “where they learned to sit still, hands folded in the Quaker fashion, and like Essie Holland had to tolerate backboards in the interests of good posture; Laura recalled their white bonnets as very becoming. She was not robust as a child and was fed on oysters for strength; she also had to submit to raw steak laid on her cheeks to put some colour into them. However she grew up healthily and went on to a French school for ‘finishing’” [2, p.33]. At one point, she also attended a school in Switzerland. When they were at home, they were primarily raised by the housekeeper, as the uncle travelled for business quite frequently [5]. This uncle also had an estate in the West Country where he bred race horses. This was where Laura learnt to ride, hunt, and jump. It was well known that she could jump holding a full glass of sherry – “and this was side saddle.” [6; 4, p.8] Laura kept her uncle’s books and bloodstock records [2, p.33; 3].

Laura and William met while out hunting, and their many common interests caused them to foster a bond that soon led to love [4, p.8]. William was in his late 30s to early 40s and Laura was not yet 20 when the couple met. In the early 1860s[2], “Laura announced her intention of throwing in her lot with his, despite strong opposition from her guardian who, faced with the loss of his efficient assistant, threatened that for the hundreds – or thousands? – of pounds she would have received on his death she should get shillings.”[3] [2, p.34; 4, p.8] Because William was already disinherited and Laura’s guardian did not approve, the couple eloped to London where they were married at Paddington [4, p.9; 5; 7]. They decided to leave England and boarded a ship they believed was headed for Cape Town, South Africa [6]. The ship, however, landed first in Australia (in either Sydney or Melbourne), and then continued on to New Zealand, where the couple disembarked in Otago and made their way up to Auckland [4, p.9; 7]. Laura was pregnant with Alice when the couple landed in New Zealand [7].

Establishing Themselves in East Tamaki

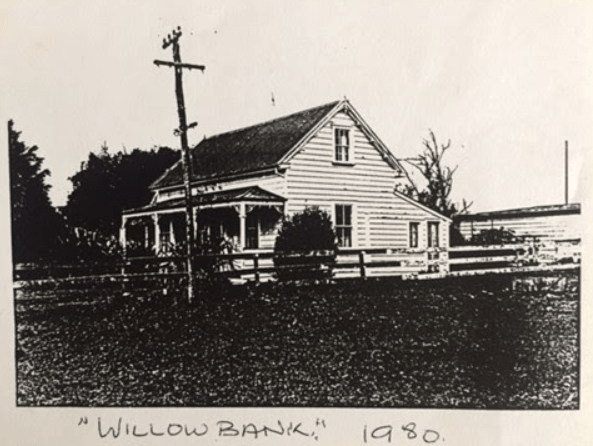

Shortly after arriving in Auckland, the Woodwards bought a farm in East Tamaki [1; 8]. The 1871/2 electoral roll lists William Woodward as the owner of a 154 acre property in Matinginui [2, p.35]. The house became known as Willowbank Cottage and is now under the protection of Howick Historical Village [4; 1].[4] The Woodwards were one of the ten first families in the area. The couple were not the best farmers, though Laura managed to pick up many of the skills needed to run the farm. She “became skilled at such diverse jobs as sharpening the tools, and unpicking her husband’s Saville Row suits for patterns from which she tailored replacements.” [4] She also learnt to slaughter the animals [3]. Alice also helped out on the farm, grooming both their horses and the horses of visitors. John Hughlings Jackson remembers one story where William Massey (the 19th Prime Minister of New Zealand) came to visit the Woodwards for an appointment and Alice was not allowed to join in. Rather, William Woodward said “my Syce will sort it” and Alice had to stand outside looking after the horses [6; 7]. She was expected to tuck her hair into her hat and act as the groom [3].

Unfortunately, the Depression hit in the 1870s and many of the farmers in Auckland struggled to make enough money to survive. Anne Hanna advised that many farmers went bankrupt as there was no such thing as refrigeration [6]. Therefore, in 1877 when Alice was six years old, William applied for and was accepted to the position of Headmaster at Pigeon Mountain School (the forerunner to Pakuranga School) [1; 2, p.37]. In July of that same year, Laura joined the staff at Pakuranga School as the new assistant teacher, as money was proving too scarce on the farm. Their youngest daughter, Margaret, was only a few months old and so came along with Laura to the school as well [2, p.37]. Laura required a teaching qualification to progress from assistant to teacher and so “taught under [William], gaining her teaching diploma under his tutelage.” [4 p.9; 7]

Alice entered school at the age of 8 and was enrolled in Standard 2. The family believes that she must have been taught at home until this point. Within the family she was considered the “smart one”, always seen with a head in a book [7]. In her first year, she passed three out of her four subjects (writing, arithmetic, and geography). She, unfortunately, did not pass her fourth (spelling and dictation), which “would have been uttered in the formidable and unfamiliar voice of the visiting inspector… enough to make any eight-year-old fail.” [2, pp.37-8] Throughout her entire schooling experience, her studies were interrupted by baby-minding and farm work, so this may have also contributed to her low grades in these subjects [2, p.39]. In 1881, she failed writing but achieved well in all her other subjects. In all subsequent years, she passed all of her subjects. In her final year of school when she was twelve, she completed Standard 5.

At one point in 1883, the school records show that all classes ceased for three weeks due to William taking sick leave. He was suffering from an ulcer which only continued to degrade, resulting in the end of his teaching career along with Alice’s schooldays [2, p.38]. Alice remained at home so that she could look after her sick father and mind the younger children so her mother could earn money to support them all [6]. It is believed that her desire to become a doctor stemmed from her time looking after her ailing father [9]. The family history book comments that no other reason can be found for her decision to become a lady doctor, as there had not been any well-reputed lady doctors in New Zealand at this time. The first woman doctor to graduate in New Zealand was not to happen until 1896 (Dr Emily Siedeberg). “I think she was maybe driven by the women’s lib movement that was starting, because she signed that petition… She signed that petition, but we couldn’t see if she’d voted. But I think she was quite an emancipated woman” [1]. She also had a desire at one point to become a missionary, and while this did not entirely occur, it definitely influenced the humanitarian aspects of her career [5].

Alice was encouraged by everyone around her to pursue her dream of becoming a doctor, and they all helped to fill in the gap in her education: the inspector of schools encouraged her, the parson she milked cows for taught her Latin from Aesop’s Fables, and she rode in the trap with the local doctor (Dr Scott from Onehunga) who taught her chemistry [2, p.39; 10, p.29]. Her father was too ill to tutor her, but it is believed that her mother continued to help her [1; 3; 11].

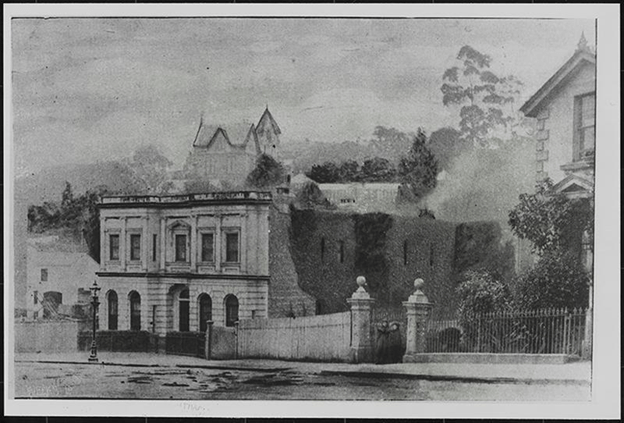

During this time, the family moved to Mangere for Laura’s job prospects. In 1888, when Alice was 18 years old, Laura Woodward obtained a position at Onehunga School (the school later opened a new building to accommodate all of the students, which was named Mangere Bridge School). Laura was appointed the first principal of Mangere Bridge School and Alice minded the three children as well as looked after her father so her mother could work [2, pp.39-40; 4; 6]. In 1893, Alice achieved the two general examinations required to enter university with matriculation in English (dictation, precis-writing, grammar, composition) and Arithmetic (fundamental rules; vulgar and decimal fractions; proportion; square root). By the age of 22, she had also passed the additional requirement of either Greek, French, German, and the elementary mechanics of solids and fluids. She entered Medical Intermediate to complete Chemistry, Biology, and Physics, which she did at Auckland University College [2, p.40]. Because the family lived in Mangere, she would walk from Mangere to the University based in Symonds Street, “as transport was erratic and expensive” [1].[5]

Otago Medical School

In the mid 1890s, Alice made her way down to Dunedin. Anne Hanna believes that she took the boat from Onehunga to New Plymouth, then the train from New Plymouth to Wellington. This was followed by a coastal boat to Lyttleton, and then the train to Dunedin. The trip was costly and took a long time, so she only returned to her family in Auckland once a year – if that [1; 3].

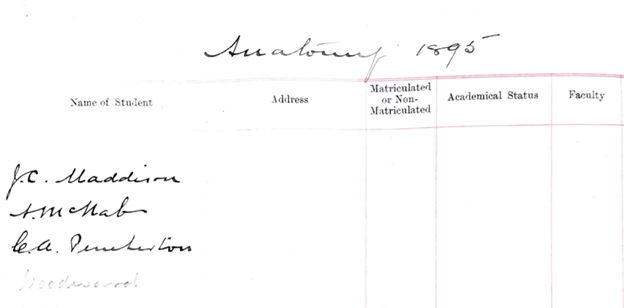

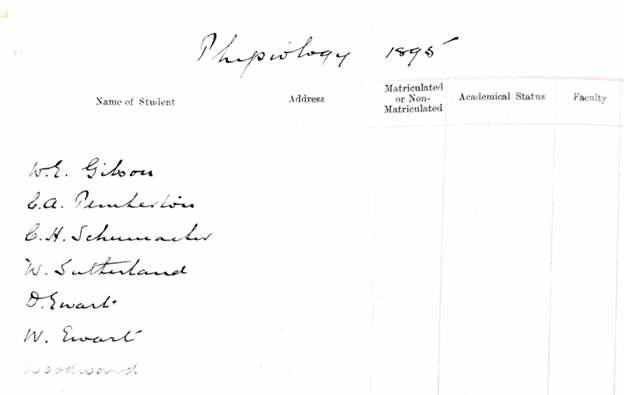

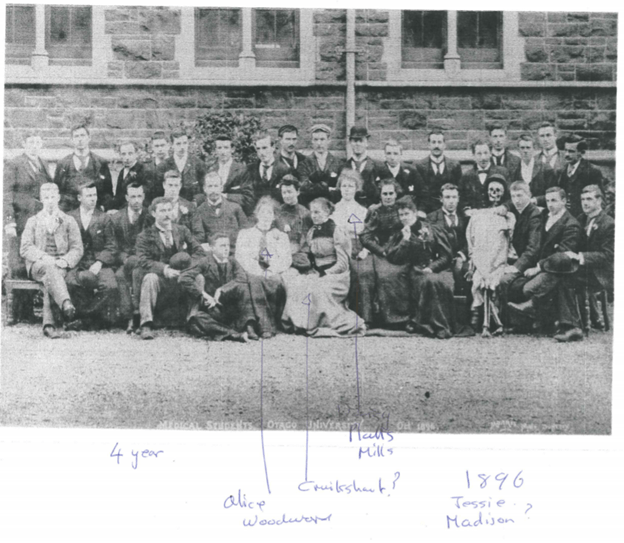

The first record of Alice Woodward being at the Otago Medical School is in the 1895 Anatomy and Physiology classes, though her family believes she may have started in 1894. These were the days before St Margaret’s College, so women had to find alternative places to board. Dr Margot Skinner from the University of Otago believes that Alice may have started in a place called Braemar House. Alternatively, she may have stayed at Girton College, which was a private boarding house modelled on Girton College in Cambridge, England. Alice did not talk too much about her living situation in Dunedin except that “she was given porridge, and if she didn’t eat it, or it got cold, it was given to her the next day… It was pretty horrible, anyhow.” [1]

She also mentioned that two students were assigned to each body. She was always the last to be chosen, which she believed was due to her being a woman: “A student to whom she was assigned as a partner for anatomy classes exclaimed that he had to do his dissection with “a blessed damozel” [2, p.41; 6]. She achieved well in every year at medical school except one. In 1897, her father tragically passed away from his continuing medical issues. “She was terribly close to her father, and was very distressed when she learned he had died” [1]. “When her father died in June 1897 she had to do her grieving alone in Dunedin” [2, p.41; 3; 6]. Because of the grief, she failed her exams that year and had to later resit them [1]. It is unknown whether this resit was the following year or if she was allowed to sit it as a special.

If she had not needed to resit, the family believes that she would have graduated in 1899 as the third woman doctor in New Zealand. Nevertheless, she completed her final exams at the end of 1899 and qualified early in 1900 alongside three other women doctors: “Constance Frost and Jane Kinder (who took up residents’ positions at Adelaide Hospital), and Daisy Platts (who registered and set up practice in Wellington)” [11]. Alice only registered in June, making her the fourth New Zealand graduate after Daisy Platts [2, p.42].

Pioneering Position at Auckland Hospital

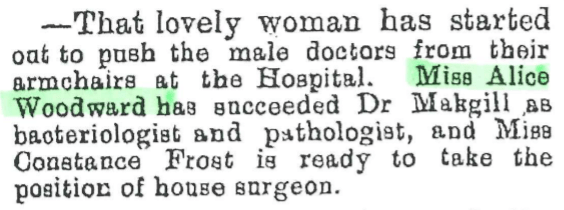

By the end of her 1899 exams, Alice Woodward had already received a position at Auckland Hospital, making her “the first appointment of a lady to the medical staff of any hospital in New Zealand” [2, p.42]. She started this position in 1900 but “was welcomed with little enthusiasm by most of her male colleagues in that conservative profession” [1; 2, p.42]. The male doctors at Auckland Hospital did not think it was a good idea for the Board to hire a woman doctor, and they expressed their opinion about this quite clearly [6].

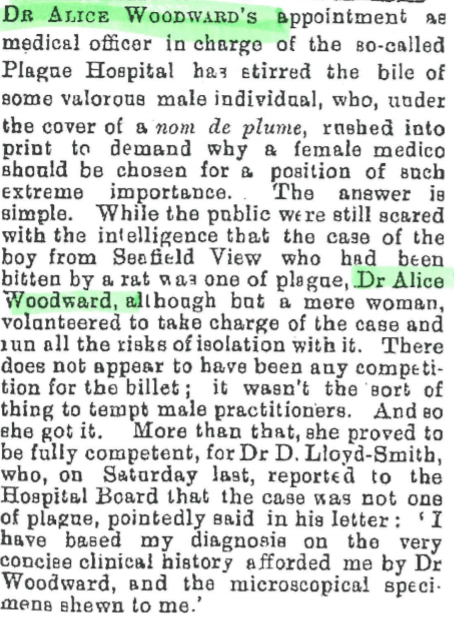

All of this changed early in 1900 with a suspected plague outbreak. News of the outbreak spread like wildfire and many of the shops and other services in Auckland closed down [3].

“But a sick rat came to her aid. It was found in downtown Auckland. Then a sick man was found, and the diagnosis was plague, awakening school-book memories of “the Black Death”, and causing some panic, in which it was proposed to set up a plague hospital in the Domain. But who was going to put their lives at risk from this fearful disease for which there was then no known cure? Young Doctor Woodward, registered only that month, offered to supervise the hospital, going into isolation for the duration of the

trouble if necessary. The feared epidemic never eventuated, though sporadic cases of plague cropped up for the next eleven years. But the heroic offer by a very new doctor was not forgotten, and did her no harm in the eyes of Aucklanders” [2, p.42].

In 1902, her position at Auckland Hospital was formalised, with an offer to become the honorary Bacteriologist and Pathologist, which is believed to have been a part-time position [11; 12]. She remained in this position until 1947 [13, p.132].

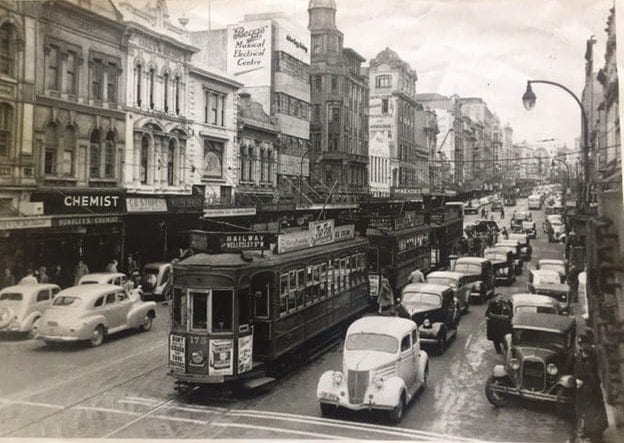

Queen Street Practice and Meeting Arthur John Horsley

After her house surgeon years at Auckland Hospital, Alice Woodward decided to go into private practice, becoming the first woman in Auckland to do so [10, p.29]. “She took a room above a chemist’s shop in Edson’s Building in Queen St, as it was usual then for doctors to set up their surgeries above chemist’s shops” [10, p.20]. Queen Street was quite bustling, with shops like Smith and Caugheys, so it was an advantageous location for her to establish her name [7; 8]. “She had the advantage of being consulted by a wide family connection, so she did pretty well” [2, p.42]. At one instance, a man turned up and requested to see ‘the doctor’. Alice responded with “I’m the doctor”, to which he replied “you can’t be the doctor, you’re a woman.” “Well come in and let’s see what I can do”, was her response and he ended up being her patient for the next 50 years [5].

The chemist shop that she established her practice over was Horsley’s Chemist Shop and a Mr Arthur John Horsley was serving his apprenticeship there. They met and quickly fell in love. She would later say “that she had won his heart with hot-buttered scones” [1; 2, p.42]. They married on 9 December 1903 at St James’ Anglican Church in Mangere and then moved into a house on Wellesley Street close to the motorway exit [10, p.29; 11; 12]. “They weren’t at Wellesley Street for long. And it was probably a small villa … There were a whole row of them that used to go up Wellesley Street” [1]. Arthur was extremely complementary to her: He was “an extremely nice man – and was he proud of her!” [2, p.42] He was constantly found observing his watch, hoping to keep her on time, and he would update her on all of the current news from the newspaper, which she did not have time to read. Bobbie Woodward said Arthur was a ‘carer’. He loved the ritual of carving the meat and serving the many people sitting around his table. Bobbie described him as a “saintly man” in his patience [3].

Both of their practices soon boomed. His chemist shop became one of the most important and busiest shops on Queen Street, and his income allowed him to support the expensive household so that Alice could run her humanitarian private practice [3]. She too achieved well, expanding her general practice to include midwifery (she even delivered her granddaughter, Mary Margaret Swaffield on 28 April 1934 [5]) and anaesthetics [10, p.29]: “She soon had no need to rely on family connections for her busy practice. She was also able to supplement fees from her patients by taking an appointment as honorary anaesthetist at Auckland Hospital. Anaesthesia was a field where women faced somewhat less fierce opposition than in other specialties, as it was comparatively poorly paid” [2, p.42]. Through her anaesthesia work, she worked with many of the top surgeons of the day. “She had a solid professional relationship with the renowned surgeon Sir Carrick Robertson at the Mater Misericordiae Hospital in Auckland. He had a reputation for being irascible and hot-tempered and it was suggested that Dr. Horsley was the only woman with whom he did not lose his temper, and in any case her unflappability and imperturbability would not have bothered her unduly. She was very sure of herself” [9].

Anne Hanna recalled one story where Alice was attending a surgery to administer anaesthetics when all of the lights in the theatre turned off, right in the middle of the operation. She was administering the chloroform to the patient but could not see. So that she could be sure how much she was administering, she dropped the chloroform on her finger, which would then drip to the patient. And it worked [1].

Potentially her practice was so successful because “she was a natural psychologist and was able to calm the violent and aggressive, as well as give comfort as well as medical advice to people on the verge of despair” [10, p.30]. To Alice, private practice was not just about the ailment but the person.

The Family House on Lower Symonds Street

In 1917, the family moved to a slightly larger house on Lower Symonds Street, which became the Horsley family home for around 50 years [1; 10, p.29; 11]. Symonds Street at this time was known as Doctor’s Row [1]. The house in Symonds Street had much personality and character, and has gone down in family history as being the definition of what a home should look and feel like: it was “unselfconsciously beautiful” [3]. Bobbie remembered that the main bedroom where Alice and Arthur slept overlooked Symonds Street and had a small balcony, and the large, main bathroom always had fluffy towels and lovely smelling soaps. The wooden floors were covered by mats and each room had an interchangeable purpose, depending on who was present in the house. The dining room was large and the sun poured in through the large windows [3]. There was an old billiard room out the back, with a billiard table that Arthur used. This room was later turned into an art studio for their youngest daughter, Jean (Byelo), who enjoyed painting [1].

Everyone who entered the house felt the generosity there and the door was always open to everyone: friend, family, or stranger [3]. “There was always laughter at Symonds Street” [1]. Relatives often stayed over, including family who came down from the Dome Valley, which meant that the extended family remained very close. They all remember there was always something cooking in the kitchen [7]. If it was not a meal on the stove, it was jam. Alice often got the urge to make jam at midnight because she did not have time at any other point in the day [5]. “She was a great jam-maker, and they talk about her making jam. And she’d often make it at night. And there was a lovely story. Her brother-in-law (Jack Jackson), I think, was having surgery, and he ran out of blood. And so they needed a blood donor. Well, of course, Nannan lay down beside him and gave her blood. And he was asked, several days later, how he was feeling. And he said he was feeling very well. He said, “But I do wake up at about 1:00 in the morning with a great desire to make jam” [1]. She would also call home during her breaks between administering anaesthetics to tell someone to turn the jam off [11].

By the front door was a knob where Alice would hang her hat. She always wore the same style of clothes, hat, shoes and jacket depending on the season. “She led a very busy life and had little time to think about clothes; it is said that she normally kept her hat on the knob at the bottom of the stairs and her medical bag was kept beside it on the floor. As she went out on her calls or to the hospitals she stuck the hat on her head without the help of a mirror and when she returned, back it went on the knob. No time was wasted” [10, pp.29-30]. A few of her colleagues “all chipped in to a fund so that Dr. Horsley could buy a new hat; she duly did: it was the same design as the old one, just a different colour. If her blouse was inside out from visiting patients in the night in a hurry she would not bother to change it. She had no sense of vanity” [9].

As well as it being their family home, Alice set up her private practice at the Symonds Street house. She converted a closed-off verandah into the patient waiting room, which was often overflowing [3; 8]. Alice did not keep regular hours, and Hughlings Jackson remembers that there were at least four people inside every time he visited. The patients would always wait, even if she was busy with non-medical matters [7]. “You turned up and you’d turn up at any hour, 24 hours, 7 days a week. And she never turned a patient away” [1]. There was only one instance the family could remember that Alice asked them to either turn people away or ask them to wait. It was during the 1940s, and she was feeling quite ill so went upstairs to sleep. Arthur answered the door and advised the patient that she was unable to see anyone at that point. The man responded, “doctors are never indisposed!” [5]

Alice never asked any of her patients for payment, which often resulted in her treating people free of charge or being paid in kind [3]. Alice Walker remembers that anyone in the Asian community would pay her in spices, most often ginger [5]. “On some occasions [she even] gave money to needy patients” [11]. And it did not end with money – many patients were seen leaving her house with a piece of furniture from the waiting room: “One of her patients, who had received free treatment for herself and her family over the years, was seen by a policeman one evening leaving the waiting-room with two chairs; he stopped her and asked where she had got them and she replied “Dr Horsley gave them to me.” He brought her back and asked the Doctor, “Did you give this woman these chairs?” and she said “Oh, yes, constable.” She admitted privately that she never put her best chairs in the waiting room, as they occasionally disappeared!” [10, p.30]. Arthur also helped. He “made up hundreds of bottles of medicine which he put down to her account, which meant they were free” [10, p.30]. At one point, Alice began to receive a government subsidy to help support the family since she gave her services free of charge..

As with many of the early women doctors, Alice had a deep desire to help unmarried mothers. She almost always had a pregnant woman living with them in the Symonds Street house or at one of her daughters’ residences, and in return they would help her with the housework [7; 11]. She believed that the mothers should keep their children if possible and so would teach them how [1; 3]. When this was not possible, she would help to organise the adoptions [5].

Extra Work Outside of the Practice

Although her private practice and anaesthetics work at the hospital was enough to keep her busy, Alice conducted extra work outside of her practice: she provided aid during the 1918 influenza epidemic, she attended the 1931 medical relief party following the Napier Earthquake, and in the 1930s she joined the Dock Street Mission as a physician.

1918 Influenza Epidemic

Alice’s involvement in the medical scene during the 1918 influenza epidemic was multifaceted. After administering anesthetics to soldiers in the Military Hospital, she would pay visits to the influenza hospitals in the CBD and in Avondale [3; 10, p.30]. While she was inside, policemen looked after her children who waited in the car, making sure they were covered with blankets to stay warm [7].

It is believed that at one point she volunteered to isolate with the flu patients when a quarantine was set up in the Auckland Domain. Because they did not have a phone at this time, the family did not know how she doing until she returned [5].[7] Due to her connection to the flu patients, everyone in her family ended up catching it. They all survived but the family remembers having to nurse each other back to good health [5].

1931 Napier Earthquake

In 1931, Alice, along with her daughter who was a Karitane nurse, travelled down to Napier to volunteer for the medical relief party [3; 6; 11]. Initially, they were not allowed on the ship and there is a story that she “sat on the [Auckland] pier and refused to budge until she was taken on the ship with her chloroform bottles around her” [1]. Eventually, she was admitted and travelled down on one of the medical ships.

Dock Street Mission

In response to the depression, the non-denominational Dock Street Mission opened a medical clinic in 1930. It operated out of the St Matthew’s Church Hall and it not only provided medical care, but many various skilled people gave their services for free [10, p.30]. In 1932, Alice received a call from this mission, asking if she could attend to a patient when another physician had refused. She agreed and from there became their regular physician [11]. The clinic ran every Thursday evening for two to three hours, and during this time Alice would see around 50 patients. These patients loved her, and some remember her falling asleep while writing prescriptions because she was so busy she barely slept [1].

“Her dedication to the clinic and her popularity within Auckland’s medical circle led her to persuade noted specialists like Carrick Robertson to see the clinic’s patients free of charge” [11]. In 1939, Alice was awarded an Order of the British Empire (OBE) award for her incredible work in the Dock Street Mission [14]. Interestingly, Anne recalled that after Alice was awarded the OBE, Carrick Robertson was heard to say in reference to the meaning of the OBE: “Oh Be Early”!

House Visits

Alice was famous for never turning down a house call – no matter how late to the appointment she arrived (people knew they just had to wait) [5]. Even if it was in a dangerous location, she would be seen walking alone. Occasionally the local police would tail her to make sure she was okay [3]. On one occasion, there was a new policeman who did not know her. All he saw was a little old lady walking down the street late one night with a bag dripping of alcohol. He arrested her and took her to the station before finding out who she was [7]. She became very well-known amongst the police, and they all loved her. A few policemen she got to know quite well even offered to carry Arthur’s casket when he died in 1950 [7].

There are many stories of how Alice travelled to her patients. She walked to many locations, though her practice spread all over Auckland (as far as Riverhead, Waitakere Ranges, Mangere, Freemans Bay, Newton Bay, etc), so walking was not always enough [8; 10, p.30]. The Horsley family had a car (“an old-type Ford with flapping curtains”) but Alice herself did not drive. Arthur would drive her the most, but the children also did when they were old enough to drive. They would sit in the car and complete their homework while they waited for her [5; 10, p.30]. Sometimes she would take a taxi, and occasionally she went on horseback when there was nothing else [10, p.30]. When she caught the tram, she would advise the driver where she wanted to go and then ask him to wake her up when they arrived so that she could sleep [8].

One story that went down in family history was when she fell asleep on a house visit. She arrived at the person’s house at about 8pm to check on their condition. One day she was up there for quite a long time and the person’s wife became concerned. She went up to the room and found both patient and doctor had fallen asleep [7].

Life Outside of Medicine

Over the years, Alice and Arthur had four children. Their eldest daughter (Molly) [8], was born in 1903 and later became a kindergarten teacher. John was born next in 1905, and followed in his mothers footsteps in becoming a doctor. Kitty was born next in 1909 and trained as a Karitane nurse, and Jean (their youngest) was born in 1913 – she was trained at Elam School of Art and as a NZ Registered Physiotherapist in the 1940’s. Though Alice was always working, all of her children emphasised that they never felt left out or unloved. She balanced her two lives (working and home) well [1].

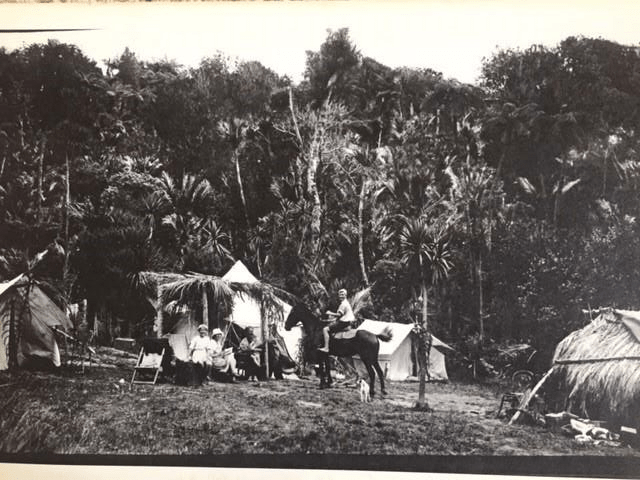

The Horsley family was quite friendly with the Bethells from Bethells Beach. They would often invite the Horsley’s to stay at their “Boarding House”. The home was very remote; the family had to drive along the beach at low tide as there were no proper roads to the house. They had to bring all of the supplies they needed: eggs, flour, tins of condensed milk, etc. The children would go fishing during the day and all water was obtained from a nearby spring, which they collected with buckets [3]. Alice became their GP and Alice’s brother ended up marrying one of the Bethell daughters. In later years, Arthur bought some land in Huapai where they first set up a whare and then later a Bush House. The house at Huapai was surrounded by enough land to allow for camping, which meant many people could stay. Graham Mandeno recalls that Alice loved these camping trips [8]. Occasionally, the Horsley’s would go camping on what is now known as Roberton Island (Motuarohia) in the Bay of Islands. Then it was owned by her brother-in-law and was called “Jackson Island”.

Final Years

Alice worked through until she was around 80 years old – she was at least working into the early 1950s when Alice Walker was born. Arthur passed away in 1950 and all her children had moved out so she was living alone at the house. One day she had a fall and hit her head. She was afraid that she would start losing her memory so she bought a few Greek books and started teaching herself Greek [5]. She was always a hard worker that would never sit still. Alice was nursed by her daughter Molly in Papatoetoe until her death on 7 November, 1957 [1; 11]. Her funeral was held at St Paul’s Church [13, p.132].

Alice was “one of the best-known and much loved general practitioners in Auckland” [10, p.29].

“In her general practice she gave unstinting care, devotion and kindness to her patients. She was loved by several generations of Aucklanders” [13, p.132].

Bibliography

- Hanna, Anne. 13 January 2021. Interview with Anne Hanna (nee Morris), Interview by Cindy Farquhar and Michaela Selway. Collection: Early Medical Women of New Zealand.

- Patricia Whitford, Woodward Questions, Self-Published.

- Woodward, Mary Daphne. 01 February 2002. Interview with Bobbie Woodward, Interview by Zana Bell. Collection: Interviews about Alice Horsley, Auckland’s First Woman Doctor. Accessed 15 July 2021.

- Mangere Bridge School Centennial Committee, Mangere Bridge School Centennial Record 1889-1989, Auckland, 1989.

- Walker, Alice Hughlings. 01 April 2002. Interview with Alice Walker, Interview by Zana Bell. Collection: Interviews about Alice Horsley, Auckland’s First Woman Doctor. Accessed 15 July 2021.

- Hanna, Julia Margaret Anne. 02 February 2002. Interview with Anne Hanna, Interview by Zana Bell. Collection: Interviews about Alice Horsley, Auckland’s First Woman Doctor. Accessed 13 January 2021.

- Jackson, John Hughlings. 28 April 2002. Interview with John Hughlings Jackson, Interview by Zana Bell. Collection: Interviews about Alice Horsley, Auckland’s First Woman Doctor. Accessed 13 January 2021.

- Mandeno, Graham Lloyd. 27 April 2002. Interview with Graham Mandeno, Interview by Zana Bell. Collection: Interviews about Alice Horsley, Auckland’s First Woman Doctor. Accessed 15 July 2021.

- Personal Correspondence between Trevor M. Landers and Anne Hanna.

- Horsley Family, ‘Life in 1900: Dr. Alice Horsley, Auckland’s first woman doctor’, Journal of the Auckland Historical Society, 32, p.29-30.

- Taonga, New Zealand Ministry for Culture and Heritage Te Manatu. n.d. “Horsley, Alice Woodward.” Teara.govt.nz. Accessed August 18, 2021. https://teara.govt.nz/en/biographies/3h36/horsley-alice-woodward.

- Royal Society, “Alice Woodward Horsley’, 150 Women in 150 Words, Royal Society Te Aparangi, Accessed 29/07/2021: https://www.royalsociety.org.nz/150th-anniversary/150-women-in-150-words/1867-1917/alice-woodward-horsley/

- Margaret D Maxwell, Women doctors in New Zealand: an historical perspective, 1921-1986, Auckland, 1990.

- Barbara L Brookes, Women in history: essays on European women in New Zealand, Wellington, 1986.

———–

[1] The family later returned to Cambridge to confirm William’s enrolment but could not find any record of his graduation nor the triple blue from this time. However, when he was in New Zealand, he requested and received a certified certificate for these studies, which he used when applying for teaching positions. It is unknown where the error lies.

[2] Some resources say they married in 1868, yet another source says they left the UK in 1863, by which point they had already married.

[3] The guardian did follow through with this; Laura only received around 30 shillings and a few silver spoons.

[4] The original plan was to move the building to Howick Historical Village, but the house has a cellar underneath that cannot be moved. Supposedly, the cellar hid Maori who escaped from the Waikato wars.

[5] The first location for Auckland University College was in the Old Choral Hall and Government House – https://www.calendar.auckland.ac.nz/en/info/history.html.

[6] https://www.aucklandartgallery.com/explore-art-and-ideas/archives/22699/item/28122?q=%2Fexplore-art-and-ideas%2Farchives%2F22699%2Fitem%2F28122&q=%2Fexplore-art-and-ideas%2Farchives%2F22699%2Fitem%2F28122&q=%2Fexplore-art-and-ideas%2Farchives%2F22699%2Fitem%2F28122&q=%2Fexplore-art-and-ideas%2Farchives%2F22699%2Fitem%2F28122&q=%2Fexplore-art-and-ideas%2Farchives%2F22699%2Fitem%2F28122

[7] This has not been confirmed or mentioned by any other family members and so this event may be confused with the plague outbreak where Alice also volunteered to isolate.