This biography is based on the family history written by Ross Galbreath, Enterprise and Energy: The Todd Family of New Zealand, and supported by other secondary research listed in the bibliography.

1923 Graduate

Contents [hide]

Early Life: Growing Up in Otago

Early Life: Growing Up in Otago

Kathleen Mary Gertrude Todd was born on 19 November 1898 in Heriot, Otago to Mary Hegarty and Charles Todd. Charles was an auctioneer as well as a Stock and Station agent. During his career, he founded the firm that was later to become known as the Todd Motor Company.[1] Charles and Mary met at the Oddfellows Ball at Tapanui in 1893, after which they quickly became engaged. They married at St Joseph’s Cathedral in Dunedin in April 1895. Charles and Mary initially moved into the Todd family home in Heriot, where Mary gave birth to four of their seven children. Kathleen was their third child.[2] However, Mary quickly found the place too small for their family and she found that she was not bonding especially well with Charles’ sisters, “who liked to gossip over the teacups”.[3]

By 1900, Charles had established himself as an effective businessman. Many of his deals had made him a lot of money, so much so that he could afford to buy his family a new and much larger home. The family was very close growing up, spending a lot of time with “crowds of cousins – the Denhams and Richards on their father’s side, the Hegartys and Shiels on their mother’s side of the family.”[4] Mary was also very religious, and she expected her children to hold to their Catholic faith as well.[5]

Heriot School and St Dominic’s: Surpassing All Academic Barriers

Kathleen attended Heriot School with all of her siblings. Each day, they walked a mile along the road through the village to get to school. Bryan, her brother, wanted to fit in better with the other boys who attended, and so he took off his boots along the way and hid them in their hedge. Kathleen achieved highly in school from the very beginning. She was a great reader, and her mother would often exclaim, “Always got your nose in a book!”[6]

Following Heriot School, Kathleen was sent to St Dominic’s Convent School for Girls in Dunedin. She found St Dominic’s was an immense change from Heriot. She had been a champion at marbles at Heriot, winning games against both the girls and boys there. However, she found that none of the girls at St Dominic’s wanted to play with her and the nuns considered the game common. Despite this, Kathleen continued to achieve highly and was awarded dux in 1915. Not only did she pass her matriculation but also the Public Service examination, which was a particular achievement.[7] The Public Service examination had two levels, the junior and senior exam, and gave those who passed an opportunity to be appointed to a position in Public Service. Though more and more girls had been sitting this exam, in 1913 the Public Service Commissioner ordered that only boys could sit the exam, as there were only a few openings in Public Service that year. In protest, a number of the “bolder girls instead sat the Public Service senior examination, which was primarily intended for public servants seeking promotion. This was the examination 17-year-old Kathleen sat and passed.”[8]

Her younger sister, Sheila, remarked that Kathleen had “a lot of go in her”,[9] because, after she passed the Public Service exam, she announced that she had decided to become a doctor. Her father was quite astonished to hear this, as he had been expecting Kathleen to work with him in his office. In comparison, Mary was very supportive. Mary came from “a good Irish family with many learned doctors, including several women doctors, and she thought Kathleen should have her chance too.” Sheila remembered that her “‘Mother prayed all night for Dad to let her go to university rather than going into the office.’ Father gave in; Kathleen could go to university.”[10]

Upon reviewing the entry requirements, Kathleen found that they required matriculation passes in English, physics or chemistry, a modern language, and Latin, the last of which Kathleen had not done. Therefore, she decided to return to school for one more year to learn Latin. She passed the exam and enrolled in the University of Otago Medical School in March 1917.

University

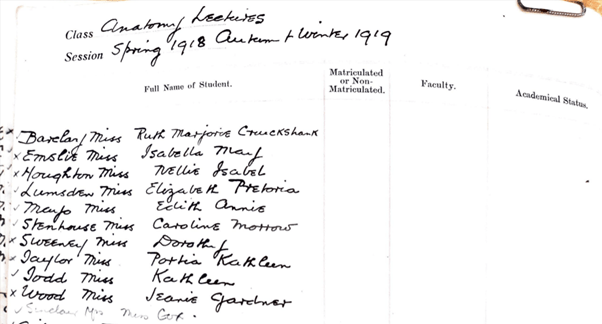

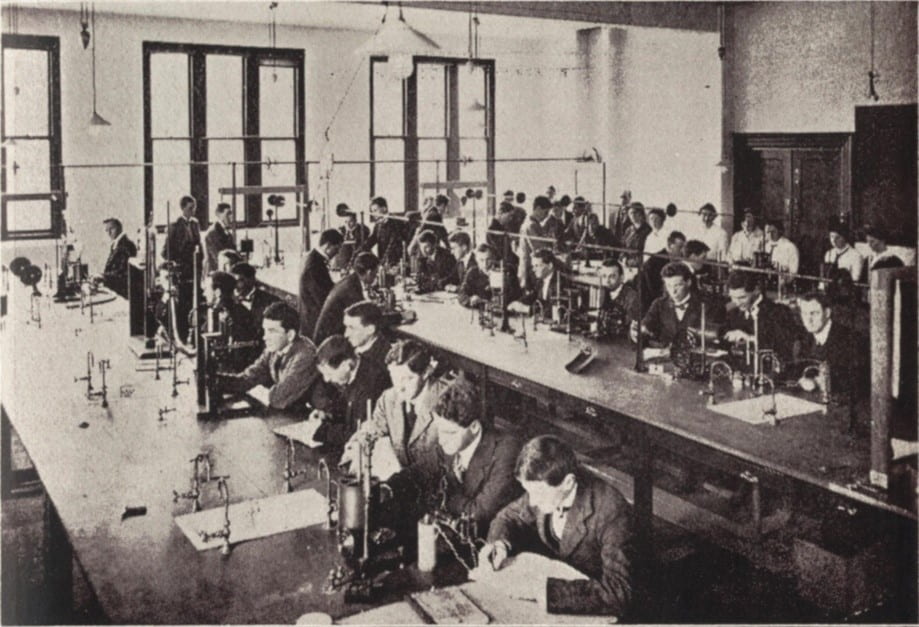

Kathleen entered her first year of medical school in the unusual 1917 intake. She was one of eight women, along with Augusta Klippel (nee Manoy) and Frances Preston (nee McAllister), out of 48 students, which was an unusually high number for women medical students. More spaces had opened up for women since many of the men were going to the war.[11] As with most women at this time, Kathleen found that school had not prepared her well for a medical degree. Out of physics, biology, and chemistry, Kathleen only passed physics in her first year.

By the end of 1918, the influenza epidemic reached Dunedin and many of the medical students volunteered to help the doctors around the country. Kathleen volunteered, but was initially turned away by Dr Gowland, the professor of Anatomy, who declared “You’ll all get it … and you must get on with your anatomy; this material can’t be wasted; we can’t give you another chance.”[12] In the end, however, he agreed that they could volunteer as long as they agreed to do three hours’ dissection every morning. As predicted, Kathleen came down with the flu but, thankfully, all of the medical students recovered. Kathleen recalled that during this epidemic, “they learned a great deal about coping in emergencies and caring for the dying: nearly a quarter of their flu patients in the hospital died.”[13]

Kathleen found that the women were constrained in many ways during their time at medical school. The women sat together during lectures primarily for protection but also because it was considered scandalous to sit next to the men. Moreover, one professor asked the women to leave the room when delivering a lecture on contraception, stating that “the subject was suitable only for gentlemen”.[14] Thus, they searched for information on this topic elsewhere and managed to learn about contraception from Marie Stopes’ book Married Love. In addition, the medical school dean argued that there was “no place for them [women] in medicine”,[15] suggesting that they should become science teachers instead of doctors. During lectures, he largely ignored the women and spoke over their heads. Despite this, Kathleen found that many of the other professors were relatively kind to the women.

In 1921, a few years into Kathleen’s medical studies, the New Zealand Medical Women’s Association (NZMWA) was formed. This was in response to the Medical Students Association (which consisted only of men) passing a new rule that women could not join. Kathleen joined the NZMWA, though she rarely attended the meetings.[16]

Outside of her studies, Kathleen upheld quite an active social life. She continued to live at home, rather than residing at the women’s accommodation at St Margaret’s, which enabled her to invite her friends over for tennis parties and supper. The factor that shaped her social life the most was her decision to pursue a career rather than a family. Kathleen was studying during the time where women generally did not continue practising after having children. A few, such as Alice Woodward, managed to practice from home so as to care for her patients and children concurrently. However, Kathleen decided that she would not consider marriage and so kept the young men around her at a distance. “When the young men pressed her with chocolates she decided she really didn’t like them, and left them for young Sheila, who did.”[17]

Kathleen finally completed her studies and graduated in 1923 along with eleven other women doctors, the highest number yet. However, she quickly found that the warnings had been correct – their medical degrees did not guarantee them a job. The few house surgeon positions she applied for all went to men. Fortunately, she was offered a locum by “the famously unconventional Dr G. McCall Smith of Rawene” and she worked there in 1925.[18] She later took up a position as Junior School Medical Officer in the Health Department’s Division of School Hygiene, which was only available because the men did not want it.[19] This role involved conducting routine examinations of children in schools.

Moving to Vienna, the United States, and England for Postgraduate Studies

After a few years of short-term locums, Kathleen’s father offered to take the family on a world trip. He had made a significant profit in the wool industry. Kathleen decided to join the trip and in 1925, the family set off in a steamer to the United States. The men disembarked at Detroit, and Kathleen and her sister Moyra continued to London and Europe. Upon arriving in Vienna, Kathleen reunited with her friends from medical school, Augusta Manoy and Sylvia Gytha de Lancy Chapman, who were undertaking postgraduate studies in Vienna. The American Medical Association of Vienna, was established to assist any English-speaking doctors in undertaking postgraduate studies. Kathleen enrolled and thoroughly enjoyed her time, making a lot of friends. She attended lectures and demonstrations in both the hospitals and at the university.[20] Vienna was the centre for postgraduate medical studies at this time, and doctors were travelling from all over the world to enrol in this program.[21] Her sister, Moyra, had decided to stay with her in Vienna rather than continuing on with the vacation.

In 1926, following her year at the American Medical Association of Vienna, Kathleen and Moyra left Europe for England, initially staying in a boarding house in Bloomsbury, London with three other New Zealanders: Hilda Valentine, and Beatrix Helen (Tui) Bakewell and Edith Annie (Jill) Mayo (who were both doctors). Kathleen obtained a position as a house surgeon. She gained experience in surgical work and received clinical instruction from the specialists there. It was here that she became interested in psychological medicine. In 1928, she moved to the United States to pursue this further.

Kathleen first landed a position as a house surgeon at the Baby Hospital in Oakland, which solely looked after babies and children. Following this, she moved to Boston to work for a privately funded institution called the Judge Baker Foundation. This institution was conducting innovative research into a new field called ‘child guidance’, which had arisen after the war when the public noticed children falling into “crime and delinquency”.[22] The leaders of this research, Augusta Bronner and William Healy, were working with young children who had been labelled as delinquents to determine the cause of their behaviour. Kathleen was inspired by this research, which combined psychiatry and medicine in a field she was already interested in, paediatrics. Witnessing this groundbreaking research caused Kathleen to return to London in 1929 to complete a Diploma in Psychological Medicine.[23] This diploma involved several practicums at psychiatric institutions. She conducted her practicums at Maudsley Hospital in Camberwell and Tavistock clinic, a Voluntary Psychotherapy establishment in Tavistock Square in Bloomsbury.

Just as Kathleen was finishing her diploma, some of her family were passing through London on the way back to New Zealand, and Kathleen and Moyra decided to join them.

“After 5 years or so abroad, you will start hearing the booming of the surf on the beaches, the smell of the bush, the stillness of the mountains and ever afterwards – you will be drawn in two directions, as are all New Zealanders who fall love with European cultivation, yet have their roots in something that has a strong deep pull here.”[24]

Early Work in Child Psychiatry in New Zealand

Upon returning to New Zealand, Kathleen was offered a position that appeared perfect for her skillset. As it had occurred in the United States, public concern was pushing for psychiatric clinics for children to address anxiety about “mental defectives” and they were looking for doctors with her experience.[25] “She had no idea of the minefield she was walking into here.”[26] The Mental Defectives Amendment Act of 1928 set up the programme to classify children from as young as possible as ‘defective’ and determine whether they should be institutionalised to prevent them from committing a crime. Psychological clinics, such as the one that hired Kathleen, were established around the country to conduct these assessments.[27]

Kathleen was offered a salary of £590, making her one of the highest-paid women in the public sector. Though Kathleen’s role was to assess children to determine whether they should receive treatment or confinement, it quickly expanded beyond this. This also occurred in the Wellington branch, where the leading doctor there, Dr Russell, reported, “When the clinics were first started most of the children examined were mentally deficient or border-line cases. As time has gone on it has been found that a gradually increasing number of normal children have been brought for advice because of behaviour problems. It has also been found that an increasing number of children have been referred by medical practitioners and brought by the parents themselves.”[28] Kathleen and Dr Russell found themselves providing more guidance than assessment, which they found created tension in the medical community because people working there were still old school and wanted the mental defectives segregated.[29]

Though Kathleen was highly paid for a public servant, she was one of the lowest in the medical community. This became worse during the depression years as her salary was cut by 20% by 1932. By 1935, Kathleen decided that enough was enough. In recent years, three men had been appointed to higher positions with higher pay despite them being younger and less experienced. She returned to London with her sister Moyra, to “the greater freedom and more stimulating professional climate overseas.”[30]

Leading a Stimulating Career in Psychiatry in London

Moyra and Kathleen established a permanent home for themselves in Hampstead, not far from a friend of Moyra’s. Their home became a meeting place for New Zealand doctors who were travelling through London. Kathleen quickly returned to her “beloved Tavi”, the Tavistock Clinic.[31] Concurrently to this, she gained a position at St Alban’s in the Psychiatric Clinic of Hill End Hospital for Mental and Nervous Diseases, and she opened up her own private practice in Wimpole Street.[32]

“It was a stimulating time for Kathleen”, as she visited and worked alongside leaders in the field of psychiatry such as Ernst Kretschmer and Carl Gustav Jung.[33] She attended child guidance conferences and even had the opportunity to present her own research on psychotherapy.

The Tavistock Clinic had to move location in response to the outbreak of World War Two, as many of the children had been evacuated out of London. This was fortunate as the old building ended up being destroyed in the Blitz of 1941.[34] The movement of men away from their careers into the army to support the war opened up new opportunities for Kathleen. Though she and Moyra had moved outside of London, she continued to travel there for work. She gave seminars on child psychology and lectured a course for mental health workers. She began consulting out of Harley Street and in October of 1941 was appointed as ‘psychiatrist-in-charge’ at the Child Guidance Training Clinic, which had been evacuated from London to Oxford, though she was never awarded the title of ‘acting director’.[35]

By 1943, it was determined that the air raids were unlikely to continue, so Kathleen helped to reestablish the Child Guidance Training Clinic in their new premises in Highbury, London. This clinic created multi-disciplinary teams to diagnose and treat children with mild emotional and behavioural issues.[36] Through this work, Kathleen became a leader in her field. She wrote the successful book ‘Child Treatment and the Therapy of Play’ with Lydia Jackson, which was initially published in 1946 and reprinted for many years afterwards.[37] This book was aimed at professionals and parents. She also contributed the chapter on Child Guidance in a practitioner’s handbook on child health and development.[38]

Kathleen received much recognition for her work in London. In 1938 she became a member of the British Psychological Society and was appointed as a Fellow in 1942. She also became a fellow of the Royal Society of Medicine in 1941 and a member of the Royal Medico Psychological Association in 1943. “She was the first New Zealander, male or female, to reach this level in the profession.”[39]

The End of the War, Returning Home to New Zealand

At the end of the war, men were returning to their positions, which led to a time of readjustment. Moyra and Kathleen decided to return home since travel had opened up. Kathleen had also been experiencing some health issues and decided to return to New Zealand to recuperate. In 1946, they reunited with their family for the first time in twelve years. Despite Kathleen’s success in her career, she found that her family did not understand and was not especially supportive. Her mother was even still disapproving of her inability to find a husband.[40]

Kathleen and Moyra ended up staying in New Zealand for much longer than initially intended. Though they had returned to allow Kathleen to recover, her health issues only worsened and she was eventually diagnosed with cerebral arteriosclerosis. Kathleen decided to remain in New Zealand and the two women moved to Wellington, buying a house on the hillside of Melling in 1949.[41] Though they had plans to establish this as a children’s home or psychiatric hospital, they did not follow through with them. Instead, Kathleen renewed her New Zealand medical registration and opened up a private practice at home, treating patients that were referred to her. She did not become actively involved in the New Zealand medical community, though she was elected to the Australian and New Zealand Society of Psychiatrists.[42]

Philanthropy and Developing ‘The End House’

Moyra and Kathleen called their home ‘The End House’ and established a beautiful garden. They played music, displayed art, and invited friends and family over. Kathleen became passionate about taking photos of her flowers, and she became a member of the New Zealand Rhododendron Association, the Pukeiti Rhododendron Trust, and the New Zealand Camellia Society.[43] Though they had distanced themselves from the family, they remained in constant contact, occasionally looking after their nieces and nephews when their brothers travelled overseas.

Kathleen and Moyra also took a specific interest in younger people, supporting them in pursuing their chosen career. They donated to the Save the Children fund which supported children in Africa, and they anonymously funded the extension of the children’s home at Qui Nhon in South Vietnam.[44] On top of this, they also focused on more personal contacts. The daughter of one of Kathleen’s friends announced that she too wanted to become a doctor, and Kathleen supported her throughout medical school.[45]

Kathleen and Moyra also believed that it was their social and Christian responsibility to donate to the community. All of the Todd children came together in August 1960 to form the Todd Charitable Trust to make grants and donations.[46] They each contributed £10,000, and Desmond Todd arranged for the income he received through his rental properties to be paid into the fund. In 1962, Kathleen established the first formal Todd charitable trust – a fellowship for young psychiatrists to pursue postgraduate studies in Europe.[47] This fellowship paid for training as well as encouraged the recipient to indulge in European culture. In return, the recipient was to return to New Zealand following their studies to further the field of psychiatry in New Zealand.[48]

Death and Legacy

In 1963, Kathleen had surgery for her medical issues, but her health continued to decline. Though she maintained her registration, she practised less and less. Her friend from her medical schooling days, Sir Charles Burns, cared for her along with Moyra.[49] On 21 March 1968, Kathleen passed away in her home at End House.

Following her death, Moyra continued Kathleen’s philanthropic pursuits.

Bibliography

Galbreath, Ross. Enterprise and Energy : The Todd Family of New Zealand. Wellington, New Zealand: Todd Corporation, 2010.

Page, Dorothy. Anatomy of a Medical School : A History of Medicine at the University of Otago, 1875-2000. Dunedin, New Zealand: Otago University Press, 2008.

Footnotes

[1] Bronwyn Labrum, ‘Kathleen Mary Gertrude Todd’, Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, 2000, https://teara.govt.nz/en/biographies/5t15/todd-kathleen-mary-gertrude (accessed 10 February 2021).

[2] Ross Galbreath, Enterprise and Energy : The Todd Family of New Zealand (Wellington, New Zealand: Todd Corporation, 2010), 43.

[5] Galbreath, Enterprise and Energy : The Todd Family of New Zealand (Wellington, New Zealand: Todd Corporation, 2010), 45.

[18] Galbreath, 146-7; Bronwyn Labrum, ‘Kathleen Mary Gertrude Todd’, Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, 2000, https://teara.govt.nz/en/biographies/5t15/todd-kathleen-mary-gertrude (accessed 10 February 2021.

[21] Labrum, ‘Kathleen Mary Gertrude Todd’.

[22] Galbreath, 149; Labrum, ‘Kathleen Mary Gertrude Todd’.

[23] Labrum, ‘Kathleen Mary Gertrude Todd’.

[27] Labrum, ‘Kathleen Mary Gertrude Todd’.

[32] Labrum, ‘Kathleen Mary Gertrude Todd’.

[35] Galbreath, 156; Dorothy Page, Anatomy of a Medical School : A History of Medicine at the University of Otago, 1875-2000 (Dunedin, New Zealand: Otago University Press, 2008), 296.

[36] Labrum, ‘Kathleen Mary Gertrude Todd’.

[37] Labrum; Galbreath, 157; Page, 296.

[38] Labrum, ‘Kathleen Mary Gertrude Todd’.

[43] Labrum, ‘Kathleen Mary Gertrude Todd’.

[46] ‘Our History’, Todd Foundation, accessed 10 February 2021, http://www.toddfoundation.org.nz/our-history; Galbreath, 289.

[47] ‘Our History’; Labrum, ‘Kathleen Mary Gertrude Todd’; Page, 296.