This biography is largely based on an oral interview with Lesley’s son, Phil Doak, in June 2021 for the Early Medical Women of New Zealand Project. The interviewer was Michaela Selway.

1957 Graduate

Contents [hide]

Growing Up in Auckland

Lesley Kathleen Harries was born on 3 August 1932 in Sydney as the only child to Sydney and Kathleen Harries. Lesley’s father was a travelling salesman and businessman/entrepreneur, a profession which enabled them to emigrate from Sydney to Auckland, New Zealand in the mid-1930s. They moved into a house in Kenny Road, Remuera. Lesley attended Meadowbank Primary for the first few years of her education and then carried on to Epsom Girls Grammar for High School. Phil recalls Lesley saying that she attended primary school with Bruce McLaren who later became a well-known Formula One Champion. Lesley remembered him missing a period of school when he contracted polio. Thankfully, Epsom Girls’ Grammar emphasised the science subjects, and so Lesley received a well-rounded education that prepared her better for university than many of the other schools at this time. It helped that she was a bright student and so she achieved academically well. “She had a very supportive family particularly her father whom she thought the world of and who supported her … And they were good buddies. He certainly encouraged and motivated her to be her best self.”

During her schooling years and with the intervention of World War Two, her father’s business interests suffered. One day, Lesley bought him an Art Union ticket (equivalent to a Lotto ticket) and they won some money. He invested this money in Tea Rooms in Wellsford, which ended up proving to be quite successful, so much so that he continued this until his retirement. Lesley’s mother would also help in the tearooms and when Lesley returned to Auckland during the summer holidays, she would work there to earn some extra money.

As she came to the end of her schooling days, Lesley decided to pursue a career in Medicine. “I think her inspiration came from her father’s belief in her. Her dad … was a character and he imparted his sense of adventure in her. I think, as a entrepreneur at the time, he was prepared to push the boundaries, and he knew that hard work was essential but not enough on its own. He was proud of her and clearly saw and appreciated her intellect, capability and capacity. Having had his own troubles in life, he must have believed that having a profession was a privilege that his daughter could and should achieve, and be self-reliant – even though that was not the female norm at the time. Through his adventurous character, he encouraged mum to believe in herself. This influence must have been very strong for mum because she was also deeply affected by less positive attitudes towards her both personally and as a woman throughout her life. For example, in her formative years mum said she was always a bit overweight, she was short, didn’t have an athletic build. And she was an only child and didn’t make friends easily because she wasn’t the “popular girly-girl” (as she used to put it). She and her dad went tramping, swimming, camping and fishing, and there are photos of them in out of reach places throughout New Zealand. I think her dad just thought she was the bee’s knees and encouraged her in every way possible. He obviously believed in her and she must have believed in herself enough to keep going. She always had grit.”

Medical Intermediate and School

Lesley decided to do her Medical Intermediate year at Auckland University College so as to remain close to family. Though she had a slight head start with her science background, she unfortunately failed zoology and so had to repeat the year. “She laughed because she said she failed zoology. She couldn’t quite work out why it was important to know anything about zoology if you wanted to be a doctor, but she failed it anyway. And that put her a year behind.”

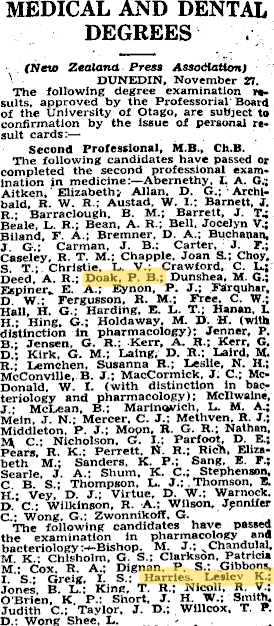

She passed the second year of Medical Intermediate and continued on to Dunedin the following year in 1953. Phil believes that his mother was financially supported by her family throughout her studies. It is unknown if she received a Government Bursary like many women in this period did. She stayed in St Margaret’s College for her whole time in Dunedin and loved the camaraderie between the women staying there. She even talked about “playing knucklebones with the dentists but with real knuckles.”

Lesley enjoyed her time at university. Her repeating of that first year ended up being a blessing in disguise though, as it meant that she ended up in the same class as Peter Brian Doak. The couple met in class and Peter invited her to one of the college balls. From then they became an item and there were many jokes about him developing a limp from holding her hand because she was 5 foot 2 inches and he was almost 6 feet. “And they used to walk to and from the colleges together.” Though they got together quite early in their studies, they decided not to marry until after their studies were complete.

Lesley was far more social than Peter. In Auckland, she had been a member of the Auckland University Tramping Club, but she did not keep this up in Dunedin. Instead, she was on many committees, and she helped to organise many of the social events. “He used to laugh at her because he’d do well at the exams and she’d sort of struggle by. But he used to laugh and say, “Well that’s because you’re socialising all the time.” So, I think she had a pretty good social life down there. But I think she was mainly with the other women at Saint Margaret’s.”

Phil remembers one particular story that Lesley told from her time in Dunedin: “She hated the sight of blood for years. And that she had to practise all sorts of odd techniques because, she just couldn’t handle the smell of formaldehyde. And so, she strategically sat next to the guys who smoked the most because they’d have their big trench coats and smell of cigarette smoke would disguise the formaldehyde. She’d prop her book up in front of her so that she could see the lecturer’s eyes but not the body and the gory activity, and she’d be looking at other people’s diagrams and notes rather than looking at the actual cadaver itself.”

Both Peter and Lesley completed their studies and graduated in 1957.

Family Life, Travelling, and General Practice

Following graduation, the couple most likely returned to Auckland where they married on 7 March 1959. After their two years of registration, Peter was pulled aside by a senior professor and advised that he should pursue postgraduate studies overseas. He was sent to both London and Boston originally to study blood diseases but while in London it was agreed that he would instead study renal medicine with a specific focus on dialysis and kidney transplants. So, he worked with the real pioneers in this field and became a leading renal physician in New Zealand. Lesley travelled with him and, while in London, obtained a position at St Margaret’s Hospital and achieved a specialist qualification in anaesthetics. She had vivid memories of the fog while in London: “Occasionally, the “pea-souper” was so thick that she couldn’t walk home or one or the other of them would have to stay at the hospital overnight.”

The couple was in London for a few years following the conclusion of Lesley’s Diploma, and in 1964, before heading to Boston, Lesley attended a Billy Graham crusade where she became a Born-Again Christian. Not long after, they moved to Boston for about a year, where they had their first child, Warren. While in London and Boston, the couple was supported by a Health Department Grant that funded postgraduate education overseas. “But it wasn’t much money because mum said that in Boston they were living in a tenement and had a very basic existence. With the baby coming along, she struggled with the apartment and day to day life in a foreign country while not working. She said it was dusty and very cold in the bleak Boston winter. At least once a week, she would sprinkle tea leaves all over the floor and sweep them all up to make sure that she got all the dust up so that the environment was ok for the baby. And dad would sell his own blood for the blood bank, to get a bit of extra money, to make ends meet.” In 1965, the family returned to New Zealand and in 1966, Lesley gave birth to their second son, Phil.

Lesley took the years of having children off work so that she could be present for their early years. However, not long after Phil was born, she decided to return to work in a part-time capacity. Though she had gained a Diploma in Anaesthetics, she decided instead to become a General Practitioner. Phil asked her once “why she didn’t continue with the specialisation. And I don’t know whether she was being facetious or not, because she could be very facetious, but she used to refer to– she said all surgeons are, in her words, skitey-bottoms. To skite is a great New Zealand word meaning to boast, but mum used this phrase “a skitey-bottom” to refer to a particular gait of superiority that she observed in surgeons generally. Although she was being comical and there were many family friends who were surgeons, she did not feel comfortable in the patriarchal environment that she had experienced in hospitals.” Instead, she wanted to work with people, so she chose general practice where she felt she could make more difference – mainly for female patients whom she felt would be better understood by a female practitioner.

After struggling for a while to obtain a position, she was eventually offered a partnership in a GP Practice in Maheke Street, Saint Heliers run by Drs Jackson and Morris. Phil described them as quite ‘old school’ GPs, but “they were fantastic to her.” “Part-time jobs really weren’t heard of back then, but they gave her an opportunity, and she was always extremely grateful to them…, I think that she built a really good practice for them as well because she was a female GP. And as St Heliers is an established older community as well as families, she was popular with older women as well as families. She worked there right the way through till she retired and became a stalwart in that community. Whenever I walked with Mum through the shops in St Heliers, we were always stopped multiple times by all sorts of people.”

One of her main responsibilities at the practice, Lesley believed, was to counsel. She often went over the 15-minute time allocation so that the patient would feel assured they were being heard by their doctor and not just rushed through. “In her practice as a general practitioner, patients, particularly women, would come to her with family issues, and often with grief. And she did have a lot of older women as patients – she said that much loneliness stems from grief, so she spent a lot of time thinking about and developing ways for patents to cope. She was a very perceptive and caring person.”

Occasionally she would work on-call over the weekends and at night to take her share of the practice’s burden, however, she tried her best to only work part-time so that she could continue to be present for her family. Like all professional women the balance is never perfect. Phil remembers that his mother “got a hard time from other mothers” due to her decision to continue working rather than be a full-time mother and wife. “Mum liked to pick Warren and I up from school – and we liked it too. Even though mum could not be relied upon to be on time! My brother and I would wait for mum at a place called The Big Tree, which was a big tree at the school that we went to. It was not uncommon for us to still be there waiting for mum to pick us up at 5:30 because she’d been called off to a patient– she would sometimes get a hard time from other mothers about that. Maybe they thought that she was neglecting us in some sort of way, but that was far from the truth. I recall that period of my life very warmly and I thought it was wonderful. My brother and I got to muck around together; we’re the best of mates as Warren was only a couple years older than me. We’d play cricket and rugby, we’d chase each other round… Mum was always very apologetic but we knew that our mother couldn’t always be there on time because she was out there saving lives. We understood from an early age the concept of altruism, empathy and duty. Mum was doing something that was incredibly important so when we heard people criticising Mum, we just smiled and rolled with it. Deep down, what better values can you have and pass on than those. Both Warren and I are professionals and have married professional women – that says a lot about mum as a pioneer.”

Because Peter was working full-time, he was earning enough to support the family, which meant that Lesley had the freedom to only work part-time. “Dad was a big supporter of mum. He believed in her. I mean, I’m not sure that it was a perfect relationship or anything like that. But they were married for over 60 years, and I can imagine that as mum used to say, some men don’t like having professional women as wives because, they feel intimidated or under-done or whatever by it. But that certainly wasn’t the case for us. I mean dad in his own way was a genius, so there was sort of no way that he was going to be knocked off his perch as sort of the brightest around. But he was always very interested by her professional activities and there was a lot of Latin medical terminology spoken at the dinner table! He was also very hands on with Warren and myself and involved in family life – perhaps not domestically – but was very active with home teaching and coaching sport. When he had time off, he came to every sporting tournament the children had. That did mean that mum had a little time to do other things.”

Even though Lesley was married, she practiced under her maiden name. The family found it funny that Dr Doak sounded like “Donald Duck” and her practicing under that name would mean that there were two Dr Doaks in Auckland, which she believed would be confusing. But the real reason that Lesley practiced under the name “Dr Harries” was to honour her father who had been so supportive of her.

Retirement and Later Years

Lesley retired slightly earlier than she could have. She found that during the 1990s, the medical field was rapidly changing in response to the growing importance of new technology and computers and she felt that the switch to budget holding adversely impacted the way that she could practice – to her, her time was not money: her time enabled healing at all levels. She retired in the mid-1990s and Peter retired just before the turn of the century.

Throughout her career, she had been a member of the National Council of Women and at one point was elected the President of the Auckland Branch. She was a very strong advocate for all women and women’s issues in society and particularly for the professional woman and her voice in the world. As Phil said, “Mum had 2 boys who were involuntarily raised as feminists”.

Inspired by his parents, Phil applied to Medical School. He was accepted, however, before he went down, his parents sat him down for an honest conversation. “They said, “Well done. Yes. We want you to have a profession. But if you want to be a doctor, make sure you’re doing it for you and for all the right reasons. Not because you’ve come from a medical family.” “And I remember them saying, “the health system is not all that it seems to be.” “And they said, “Being a doctor means that you could get trapped in a system. So, make sure that you love it. Because you’re not going to be able to change halfway through. That will be very difficult”.” They also both felt the field was becoming more money and committee focused and less attention was placed on the patients themselves. Therefore, Phil ended up going into law and commerce instead. Warren became a financier and banker.

After retirement, Peter and Lesley both began to have some health problems. Lesley developed arthritis in her legs and increasingly struggled to be mobile. Likewise, Peter’s brain slowly deteriorated. After a long and happy married life together, Lesley passed away on 25 September 2019, aged 88. Peter passed away one year later on 12 December 2020, aged 88. They are survived by their two sons, five grandchildren and one great-grandchild.

“So she was a pioneer as a female doctor and she was also a pioneer as a professional woman, and having the balance of being a wife, a mother, and a professional without role models around to do that. The older I got, the more I realised what a wonderful job she did of that, and what a fantastic mother she was to me, and it certainly framed me up for success going into the future She taught me how to care genuinely and how to love selflessly.”

“I remember talking to dad before he died, and he died a happy man. And the same with mum. They had lived a very fulfilled life. And I should say my mum was a Born-again Christian all her life and so she always had a role in the church. Dad had been agnostic for many years, but, following a rigorous academic exploration in his retirement, converted and that I think was probably due to mum… In any case she believed that this was her greatest achievement.”