This biography is largely based on an oral interview with Monica Lewis conducted in October 2022 for the Early Medical Women of New Zealand Project. The interviewer was Rennae Taylor. Other sources are listed in the bibliography. The biography was constructed by Monica and Rennae.

Class of 1967

Contents [hide]

Family History and Childhood

Beryl Monica Moody (always called Monica) was born to Edward Henry and Beatrice (Bea) Moody in the city of Kunming, Yunnan province, China on 22 March 1943. Three years later (while on furlough back in England) Peter, her younger brother by three years, was adopted through Barnardos into their family. He is also an Otago Medical School graduate (class of 1973) and is now a retired Christchurch general practitioner (GP).

Both her parents were born in the United Kingdom – her mother in 1905 and father in 1907. Her mother was adopted as a baby by an older couple, had a strict upbringing, was involved in their local Baptist church, and grew up with a great love of reading (particularly non-fiction). Later in life, she wrote book reviews for the Daily Telegraph. She did her nursing and midwifery training at the Royal Free Hospital in London and at the age of twenty-three was accepted to be a missionary to China by the Baptist Missionary Society. Part of the criteria for acceptance was the requirement to be bonded to the mission for seven years. She was not allowed to get married during this time.

Monica’s father had received his theological training for the Methodist ministry in England. He offered his services for overseas mission and in 1932 was appointed by the Methodist Missionary Society to China. He and Beatrice met at language school in Peking, China and most of their courtship, after language school, was via letter as he was sent to the Shanghai area and she was posted to the X’ian area – over a thousand miles away. After six years, her father was able to pay £200 to have her bond reduced by one year. His wedding gift to his fiancée was a black stallion which she rode with a Chinese servant for six weeks, staying in very basic Chinese inns. One of them had to stay awake during the night, in the straw next to the horse, to ward off the rats who would otherwise eat the horse’s hooves and tendons. They eventually were reunited and were married in Hong Kong. Beatrice then came under the umbrella of the Methodist Mission Society.

As a married couple they were sent to a very remote area in the Yunnan province near Tibet to live among the Miao, a poor Chinese ethnic group, who had no written language. It took them two months to make this journey on mules from Hong Kong. Her father did translation work of the Bible into the local Miao language and her mother, who Monica described as a very quiet, organized lady, ran a hospital, outpatients clinic and leper colony with very basic supplies. Together, they also ran a school and an orphanage. A visiting doctor came about every three months. It was not uncommon for bandits, high on opium, to attack the mission station. On one of these attacks their house was burned down, and Bea had to escape by jumping from a high window which caused her to lose her first “full term” baby; she was told she would never be able to have further children. Monica’s parents worked here for several more years. Sometime during World War II, her mother was approached by the British Secret Service to submit a twice weekly report on Japanese airplane and ship movements which she naively did throughout the war using morse code. Several years later her husband queried what a regular fixed amount of money was for. Much to the family’s surprise, they discovered it was payment for Bea’s wartime work as a foreign intelligence spy.

Prior to 1942 they were moved to the city of Kunming due to the continuing bandit attacks. In mid-1942, Bea unexpectedly found she was pregnant – Monica was born in March, 1943. Following her birth, the family remained in Kunming on a large mission compound in an area called “Stinking Brook” where her mother again ran a hospital and orphanage, and her father continued his mission and translation work. Monica lived here with her parents and later went to school until she was seven years old. She was given a lot of freedom to wander around the compound as a youngster. One thing she remembers from these early years was each morning going to the gate of the compound with someone to pick up the baby girls who had been left on the doorstep overnight since many families saw no value in having a girl.

In 1950, the communists forced them to leave China but obtaining a departure visa from them was almost impossible. Many of their mission friends were brutally killed and their homes ransacked as the communists looked for hidden wealth. The Americans eventually gifted her family a jeep, with specially rigged hidden petrol cans so that they were able to escape east to Hong Kong. There, they were put on a cargo ship bound for the United States. Monica was very traumatized by these events and has no memory of the two – three years around this time. Despite being very fluent in the Mandarin language, from this time she was unable to speak it although even today she still understands it when spoken. In later years, she has been able to revisit the area of her childhood and was able to take six small bags of her mother’s ashes to sprinkle in areas which would have been significant to her mother, including into the water from the bridge across from their home in Stinking Brook.

The family eventually arrived in the United Kingdom circa 1953. Her father initially worked as a minister for the Methodist Church at Stoke-on-Trent for four years before he went into the service of the British and Foreign Bible Society as senior regional field secretary which took him to many parts of the United Kingdom. In 1964, he was made general secretary of the society in New Zealand and he and his family immigrated to Wellington, New Zealand. (1) He passed away in 1972 at the age of sixty-four.

Looking back, Monica sees herself as a dysfunctional child and her education, until she was eleven, was very fragmented. She thinks she went to thirteen schools (within China, the United States and the United Kingdom) prior to being sent to the Methodist owned boarding school, Edgehill College in Devon. She completed her intermediate and secondary school years there. She was a diligent student and tried out for everything. She enjoyed singing, learned to play the cello, received awards for her penmanship, and participated in many sports. She had red hair and believes this made her stand out at school, so she tried very hard to be compliant despite having quite a stubborn streak. She became very unhappy at the beginning and end of terms as she knew the holiday would entail yet another separation from her family; she had no desire to go away to school and desperately wanted to be with her family after the trauma of her earlier years.

She believes her strong desire to help people was the main driving force behind her decision to become a doctor. She was told she could not do medicine because the school did not offer the science subjects required. Her stubborn streak benefited her, and she was able to attend the local boys school to study physics and chemistry. She failed physics, so after graduating from Edgehill she attended a technical college to obtain credentials in this subject. Her family were very supportive of her career choice but could provide very little in the way of financial assistance.

Medical School Years (UK 1962 – 1964; Otago 1964 – 1967)

Her entrance to medical school was helped by her well-rounded education. Charing Cross Hospital Medical School were interested in students with good marks but who also had musical and sporting interests. She was accepted and started her two years of pre-clinical medical school classes in August 1962 which she had no problems completing. She spent her first two non-clinical years here prior to being uprooted once again. This time for New Zealand.

She has no idea what transpired with her father, the NZ Bible Society, Charing Cross Hospital Medical School, and Otago Medical School but Otago were prepared to take Monica into their program immediately following her arrival. The Moody family travelled by ship and arrived in Wellington at midday and that evening, sometime in September 1964, she was put on the overnight Māori ferry bound for Lyttelton. Monica describes the trauma of her next few days:

It was a bit traumatic — we came by boat and arrived in Wellington, and the boat docked at midday and that night I was put on the Māori ferry to go to Christchurch. I wasn’t given tickets or anything. I had no money. I didn’t know where I was going to stay, but I knew somebody would meet me at the railway station in Dunedin. I was so upset and distressed I couldn’t even sleep on the Māori because I was scared I wasn’t going to wake up. I had no idea they brought you bread and a cup of tea in those days. My clothes were all wrong. It was a hot, hot day and I was in a big winter coat and I had no money. So in England you don’t get on the train without a ticket, but then the Māori gets in and it’s a little train that goes to the railway station, and I was tearing around trying to find out how to buy a ticket for that train. And of course you don’t, you just get on.

But then the train to Dunedin stops at Ashburton, Timaru, and Oamaru, and everybody gets off the train, which I did, I didn’t know why, and it was of course to get your pie and your drinks. There was no food on the train, and I had no money so I couldn’t get anything so I had no food all day. I arrived in Dunedin about 5:30 pm and nobody was there to meet me, and I just didn’t know what to do. And I waited on the platform for about an hour and then a taxi driver who had been watching me, came and he sat with me and asked me what the problem was. I replied I was supposed to be picked up. And he said, “Don’t worry dear, I’ll take you. Where would you like to go?” I said, “I’ve got no money.” “No problem, doesn’t matter. Where would you like to go?” “I don’t know.” “But you must know where you’re staying.” “No.” “Can I ring somebody?” “I was told somebody would meet me but I wasn’t given a name.”

Anyway, he said, “Oh well, I’d better just sit here with you until somebody comes for you.” And we waited another hour and a half, and it was actually the daughter of the registrar of the university who’d been kept in at a lab, hadn’t been brave enough to say, “I’m supposed to be meeting this English girl. She finally met me at about ten to seven, when I’d been sitting there for two hours and she took me to the hostel where I was staying. She said, “Now just dump your bags because we thought you’d like to go to the New Zealand Symphony Orchestra.” I’d had no food all day. I hadn’t slept on the Māori and I was just sort of numb. Got to med school the next morning, and a Professor Donnell, a medical professor said, “Right, today we’re going to listen to hearts and we want three volunteers to strip to the waist.” And all the boys turned to the nine girls in the back row and went “Strip to the waist” and of course I laughed, but that joke went on for half an hour, and it wasn’t funny by then. I just wanted to go back to England. Eventually a couple of boys volunteered, one of whom ended up being my husband. So that was my very traumatic introduction.

I had no money. I went to the bursar to ask about a bursary, and they said, “Well you can’t. We don’t know anything about your degree. We don’t know if Charing Cross Hospital London University is a good medical school. I don’t think we can give you a bursary.” And I argued and I said, “Well I’ve got to live. I’ve got no money.” And eventually they offered me a first year bursary and I said, “That’s absolutely fine, but I will be claiming it for four years.” “Oh.” So eventually after about three weeks I finally got some money, so that wasn’t great either.

Monica had no particular goal she was aiming for as she progressed through her clinical years at Otago medical school. She just knew she wanted to help people. Looking back, she says that even as a young child “People have always been my hobby. I love watching people.”

She always had holiday jobs – one summer she worked for Kodak, another for a laboratory making blood agar plates – nobody would give her blood, so she regularly took blood off herself to make the plates. Earlier, while in England she worked in France as an au pair and another summer as a hotel waitress in Switzerland.

She stayed in the hostel her first months at Dunedin along with several other women medical students from her class of 1967 including Janet Lewis (later Dunlop), Ailsa Barker, Pat Cruickshank (later Hill) and Ann Philipp (later Lang). She thinks her year consisted of 120 students of which nine were women. Unlike earlier Otago medical school years, Monica recalls all the women sat in the back row of the lecture hall. Her first day at class she dressed as she would have in England – a black polo neck sweater, a red miniskirt, black stockings, and high heels. The fellows catcalled all the way up the stairs as they walked right to the top. And then the business of “strip to the waist” started!!!!

Monica’s first trip back to Wellington at the end of 1964 was very memorable. Ann Philipp asked her in October if she would like to go back to Wellington the long way or short way when the year ended. Monica suggested she was happy to do the long way (little knowing what that entailed); she and Ann hitchhiked over to Haast going through sections of virgin forest. She remembers having to run the last five kilometers in order to catch the tanker which only came into Haast once a week. They then travelled up the west coast on the tanker.

On her return for the 1965 school year Monica went into a flat with five other women for the next two years – most were in the home science course. It was a fairly large flat and they all had their own bedroom. She worked very hard during her years at Otago and did not have a lot of time for social activities but did enjoy going to the ball. The biggest challenges she faced personally were finances and homesickness. She always got home for the summer break, but other breaks were dependent on availability of finances.

She had no intention of getting involved with anyone, as she had ended a serious relationship with her boyfriend in England since she saw no future in maintaining it from half-way around the world. However, early in 1965 she had her first date with her future husband, Gerald (always shortened to Gerry). Her first date was on the back of his motor scooter – going to the Anglican Church Bible class.

Monica enjoyed all her subjects and can still remember doing her fifth-year public health project on “Burns in children”. She felt her lecturers were very good but recalls the traumatic, negative experience with her final year professor of orthopaedics.

When I walked into the room for my orthopaedics final oral – as I walked through the door, he said, “Down on your knees.” I said, “What?” “You heard me. Down on your knees.” And I said, “What do you mean?” He said, “I want you down on your knees.” So I did get down on my knees. And he said, “That is where you’re going to stay all through this oral. And that’s where all women belong.” And I never saw anything above an ankle. So they have all these cases for me to look at, and for all of them I was on my knees, and he wouldn’t let me get up between. I had to crawl from one patient to the next.

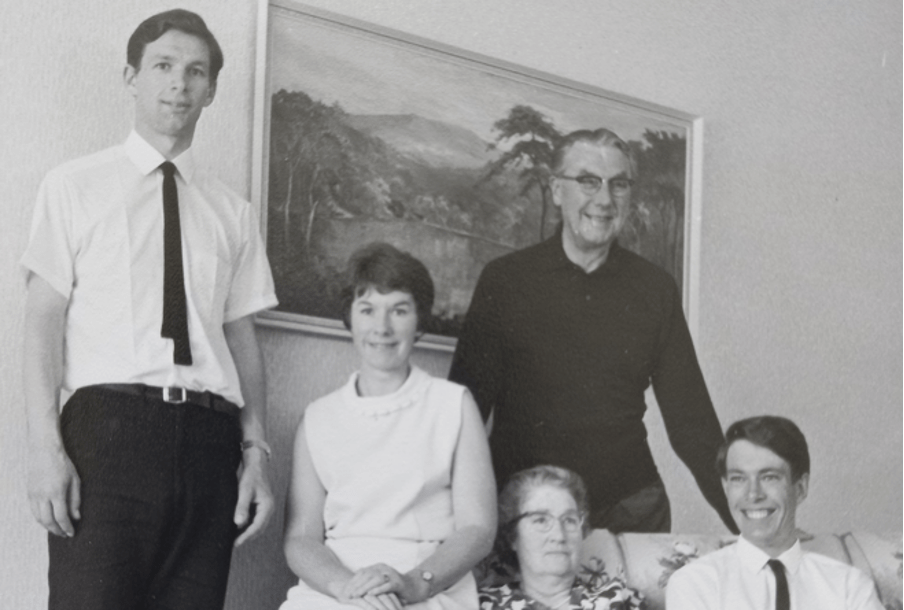

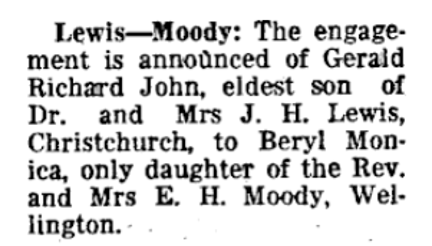

Monica and Gerry continued their courtship throughout their medical training and were engaged in August 1966. (2)

Knowing that husband and wives were not allowed to be house surgeons at the same hospital, Monica and Gerry decided to get married at the start of their sixth year so they would have one year together before being separated for their two years as house surgeons.

They were married early in February 1967, lived in a flat in Cashel Street, and spent their sixth year at Christchurch Hospital. Monica did not feel there was any distinction made between the men and women students – they were treated the same by most staff and patients. However, there was one tradition which was the exception. At Christmas time, the male student doctors would dress up as fairies and angels and the fire engine with its siren would come to increase the party atmosphere. The women student doctors had to continue working while the male students “went off kissing all the patients and nurses”.

House Surgeon Years (1968 – 1969)

The following two years as house surgeons were difficult for the newlyweds. Gerry stayed on in Christchurch and Monica went to Ashburton (the closest hospital to Christchurch that she could go to). There was no assistance given to try to provide any alignment of her schedule with Gerry’s so seeing each other was very hit and miss.

She was very thankful to be accompanied to Ashburton Hospital by her good friend Jocelyn Williams who, against the odds, had gained entry to medical school and completed her training despite having her legs in iron braces due to polio. They were the only two house surgeons at the hospital so the hours were long – often 120 hours per week. During the day, Jocelyn concentrated on surgery and Monica on medicine, which went from eight in the morning to six in the evening. Once six o’clock came, whoever was on duty (every other night) did everything including deliveries and even the occasional surgery such as hysterectomies. Every other weekend, one of them was on duty. It was a scary time for the young graduates who were given much responsibility with minimal support. During this time, in the middle of her first year at Ashburton, Monica became very ill with chicken pox and was sent home to Christchurch to be looked after by her mother-in-law for three weeks. Jocelyn had to do double duty during this time.

Monica does recall taking a woodwork course while living in Ashburton. She said the other members of the class were very friendly until they found out she was a doctor. The camaraderie between them then left. For a long time, this incident caused her “to not let on she was a doctor” in social situations.

During her second year she became pregnant and birthed her first daughter, Deborah Jane, in early November 1969.

Early Career in Christchurch and England (1970 – 1982)

Following her two years in Ashburton, Monica returned to Christchurch and started doing locums in general practices while Gerry started on his residency to become a physician. Her father-in-law was a GP, and she did a locum for him. On his return, she purchased the practice from him and then he continued doing a bit of locum work for her. The practice was in a beautiful, old home known as “The Old Vicarage” – today a popular café. (3) In between her work as a GP, she had her second daughter, Susannah Kate, born in January 1972.

In April 1972, Monica and Gerry, along with their two daughters aged three months and two years, went to England so he could continue his post-graduate training in cardiology. He was at the Walsgrave Hospital, Coventry during mid 1972 – 1973 for one year, was a research fellow in clinical pharmacology at the Hammersmith Hospital, London during 1974, and a National Heart Foundation cardiology research fellow at St Thomas’ Hospital, London in 1975. (4)

While in England, Monica did some work as a GP in different practices in the cities where they were located. It was her intention not to work, but Gerry’s scholarship was only £3000 per year, and this barely covered their rent. Childcare was difficult to find and without family support, she was forced to make some hard decisions – whether to send her children into the home of a doctor’s wife and they would come home clean but unhappy or next door to the young, smoking mother with six children and they would come home filthy but happy.

While overseas, they had some wonderful travel times. They owned a Volvo Estate car and travelled all over England and parts of Europe in it. Once, Gerry was provided with a first-class ticket to do a six week lecture tour around the world – he swapped it for an economy ticket and had enough for the whole family to travel with him.

On their return to New Zealand, they spent the next six years in Christchurch. Gerry worked for the North Canterbury Hospital Board as a cardiologist and general physician and Monica returned to working part-time as a GP in the Old Vicarage. During these years he set up the cardiac rehabilitation service and he did ground breaking research into the introduction of calcium channel blockers for the treatment of hypertension rather than only just for angina. (5, 6) Today it is routine treatment and his discovery is recognized in the 1982 publication of Whos Who in Medicine. (4)

Later Career: Napier (1983 – 1998), Wellington (1999 – 2001), Auckland (2002 – 2012)

Gerry was keen to get involved in more teaching, so in 1984 he was appointed by the Hawkes Bay Hospital Board to work at Napier Hospital as a general physician -cardiologist. Here he became involved in the education of the staff, including the nurses. Monica continued to work part-time as a GP in different practices during this time and birthed her third daughter, Amanda Joy, in February 1984. She was also involved as a family therapist with the family courts.

With the closing of Napier Hospital in 1998, they moved to Wellington where Gerry took up employment as a cardiologist at Wakefield Hospital. He did not enjoy working in the private sector so when Salus Health, Inc. head hunted him to be medical director and consultant cardiologist at their Auckland premises they relocated. He set up New Zealand’s first CT scanner for detection of calcium (calcium scoring) to assist with preventative cardiology. At this time, it was a controversial screening practice and Salus Health, Inc. was closed. He practiced privately as a cardiologist and physician and for a couple of years became employed at the Centre for Advanced Medicine which included alternative therapies such as chelation therapy. From 2007 to 2012 Gerry did locum physician posts throughout New Zealand. (4) During this time Monica was working from home and established a holistic practice seeing patients with chronic and complicated health issues.

Taupo (2012 – present)

In 2012, Monica and Gerry moved to a rural property near Taupo and ran their private medical consulting practices which included on-line consultations. (4) Gerry was often able to provide a medical opinion to those who would not normally be able to access a physician. He passed away at his home on 24 January 2020 at the age of seventy-eight. In 2008, when she reached sixty-five, Monica dropped her medical registration but continued to work as a health coach. In 2021, Monica moved into her present home in Taupo and enjoys her garden which looks out on a tranquil bush reserve at the back. She has also developed an enjoyment of snorkeling in warm waters.

Monica’s eldest two daughters live in Auckland: Deborah runs her own accounting company and Susannah, also a graduate of Otago Medical School, works at Starship as a Paediatric Emergency Medicine Specialist and at the University of Auckland Faculty of Medical and Health Sciences as an honorary lecturer in paediatrics. Her youngest daughter Amanda lives in Taupo and is involved in the travel industry. Monica has five grandchildren and enjoys family times with them.

Present Interests and Advice to Future Women Doctors

Monica’s present interests have grown out of her lifelong observation of people and her desire to help them. This early interest started her journey of thinking outside the parameters of her medical training.

A very significant event which occurred in London during her first year of medicine made her realize that medicine doesn’t teach you all there is to know. Monica and five other medical students were going to a twenty-first party. The “little, quiet student” in their class, offered to drive his father’s car to the party and behind the wheel on a rainy night “he became a maniac”. A traumatic car accident occurred which resulted in the motorcyclist he hit losing his leg and her friend Jane having a permanently paralyzed arm – she subsequently left medical school. It also resulted in Monica being thrown about fifty meters, going through a hoarding, and landing in the mud. This resulted in her scalp splitting, her face coming down, and being kicked by someone who said, “this one’s a goner”, to which she replied, “I am not”. This accident resulted in her having severe headaches for several months after the outward healing had occurred. Someone suggested she try an osteopath – the manipulations to her neck fixed her headaches.

Monica describes her journey as she started out as a GP and how her practice evolved:

I realized I was very unhappy in medicine because I wasn’t fixing people, and the very first thing I did was to take a course called “Listening with Love” for three months, and that taught me to actually listen, which doctors aren’t very good at. I could no longer do a quarter of an hour appointment, so at that point I looked to how to change my practice, and I started working with people who are chronically ill and would have an hour and a half for a first appointment. I think what I became is a bit like a “medical life coach”, looking at all aspects of their life and what they do and didn’t do, and how they could make changes. I likened it to the game of Pick-Up Sticks, which is hard to start with but then it gets easier as you pull the problem apart. And that’s what I’ve done.

And along the way having Gerry, I only had to say I was unhappy and he would say, “Well, you’ve got to do something about it. Go and find something.” One day I said, “I don’t understand how energy works”. So he sent me to Asia for three months and I looked at acupuncture in The Phillippines, Hong Kong and Singapore, and it blew my mind. That was when I realized that we have restricted ourselves so much with our methods of treatment since we invented drugs, and I remember my father-in-law saying, “I just don’t understand modern medicine. When Mrs. Jones had a heart attack I’d go to her house and I’d sit on the edge of her bed and hold her hand and she’d tell me how lonely she was since her husband had died, and we’d talk, and I’d say a little prayer with her, and then she’d give me a chicken and she felt better and I went away.” And he said, “Now we can’t do that, medicine has become linked to time which it never was”.

I became an expert in natural hormones, bio-identical hormones. In 1974 I started to hop up and down and said if we use the pill like this we’re going to have hormonal issues because back then you only slept with your boyfriend once and often you were pregnant whereas now we’ve got infertility, polycystic disease, endometriosis; male sperm count has gone down to less than half, all of which is hormonal imbalance. So that’s another area I’m very interested in and still give seminars. Supplementation is also important because our food isn’t what it was. I discovered that although I’m quite a shy person I really love giving seminars about the things I know. For the last 20 years I have travelled all over the world (USA, UK, Australia, USA, Malaysia, Hong Kong, Singapore, and Philippines).

Gerry and I were majorly into reversing disease rather than just treating it …. For instance, magnesium and fish oils lower blood pressure but doctors don’t recommend it. They go straight to drugs ….The soil has become really deficient in magnesium …. It’s that whole science of understanding how to get something into the body that should be in our food.

Monica and Gerry became medical practitioners who brought together their medical knowledge and enhanced it with alternative, complementary therapies. They shared this knowledge through their practice and seminars and together wrote several books which explained their philosophy. (4)

Monica believes the main achievement of her career is using the knowledge she gained from her medical training, building on this base, and then being able to impart this enhanced knowledge to thousands of people through seminars and one-to-one consultations.

She continues to act as a life health coach to those who come across her path – at the present time she is walking alongside someone who asked her for help to change entrenched habits; a sixty-eight-year-old person who spends $20 per day on cigarettes plus a significant amount on alcohol so has little money left for food. She is involved in the Taupo Baptist Church and helps with community activities. She is often able to give advice and encouragement to those facing difficulties.

She was asked what advice she would give to a woman considering medicine today to which she replied:

I read a few years ago that half of all doctors want to be out of medicine within five years and I think it’s worse now because they’re not getting the satisfaction of what they’re doing..… I tried really hard to encourage my daughter not to do medicine because I really felt that so many doctors are unhappy so if they’re going to, I think you’ve really got to think of a field where you really know you would like to be working, where you can really make a difference, and get some real job satisfaction and I don’t actually think that’s general practice anymore.

Monica was very excited to attend a two day medical conference recently put on by a new company called Prekure which is championing a preventative medicine movement. (7) One hundred and eighty doctors and other health care workers attended. The message was that medicine, as it is currently being practiced these days, is “broken and far too costly”. It is frequently not supplying the needs of the most vulnerable. It is hoped that moving towards prevention and lifestyle changes may bring about exciting new opportunities.

Bibliography

- New Secretary of Bible Society Arrives In N.Z. Press. 1964 10.11.1964. Available from: https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/CHP19641110.2.78

- Engagements. Press. 1966 31.08.1966. Available from: https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/CHP19660831.2.19.9

- Wine & Dine The Old Vicarage Christchurch 2022 [19.12.2022]. Available from: https://www.christchurchnz.com/see-do/wine-and-dine/the-old-vicarage

- Lewis G. 2022 [19.12.2022]. Available from: https://www.linkedin.com/in/gerald-lewis-ba068630/details/experience/

- Lewis GRJ, Morley KD, Lewis BM. The treatment of hypertension with verapamil. NZ Med J. 1978;87:351-4.

- Lewis GRJ, Morley KD, Maslowski AH, Bones PJ. Verapamil in the management of hypertensive patients. Aust NZ J Med. 1979;9:62-4.

- Prekure 2022 [19.12.2022]. Available from: https://prekure.com/