1955 Graduate

This biography is based on documents and pictures from the family’s collection provided by Gwenyth’s son Anthony.

Contents [hide]

Early life

Gwenyth Marie Hookings was born on 26 March 1929 in the Auckland suburb of Onehunga. She was the fourth of five children of Australian-born bank manager Will (William Richard Jeffery) Hookings (1894-1952) and schoolteacher Alice Mary Coward (1891-1971). (1)

Will was born in Broken Hill, New South Wales, the youngest of nine children of James Hookings (1852-1934), a carpenter, and his wife Eliza Jane Ferris (1852-1931), both from Devon, England. They married in 1876 in Walsall, Staffordshire before emigrating to Australia, and later to New Zealand. Alice’s parents, Charles Edward Coward (1859-1927) from Nelson and Mary Alice Webster (1865-1948) from Blenheim had married in 1889. Through Charles’ forebears, the family prided itself on being distantly related to Noël Coward.

Will was working in a Napier bank when he met Alice in Taradale, a suburb of Napier, where she was teaching, having grown up on a farm in Woodville, in the Manawatū. The couple married in December 1919.

After the birth of their sons, Gordon (1920-2017) and Alan (1922-2010), the family moved in 1923 to Devonport. A daughter, Jean, was born in July 1924, but died aged three in March 1928. Just four days earlier, the family had moved to Onehunga, where Will had become manager of the Auckland Savings Bank in Queen Street. They lived in a flat above the bank and Gordon recalled (in an unpublished memoir) (2) that his father kept a revolver under the counter in case of robbers. This gave his son occasional nightmares that bandits might try climbing the fire escape to their living quarters – fortunately something that never happened.

When Gwenyth was nearly two, on 3 February 1931, her paternal grandmother and aunt were killed in the Napier earthquake. Will’s mother Eliza was visiting from Auckland, and she and her daughter Ethel Mary (known as Mollie, born 1884) were having morning tea in Blythe’s department store when the earthquake struck. Six months later, when Alice and Will welcomed another daughter, they therefore named her Mollie (1931-2021).

During the Depression years, Gordon remembered, “the unfortunate men on the ‘dole’ had to queue up each week to enter the Post Office across the road from the bank to collect their unemployed benefit.”

Despite the challenges of growing up during hard times, Gwenyth later recalled a happy Onehunga childhood, including one especially memorable gift: “I was given a second-hand bike for my tenth birthday and Dad took me down to a flat grassy area at Captain Springs (ten minutes walk away) to teach me to ride.” (3) The beloved bicycle was well used. During Gwenyth’s teenage years, she and three friends took long cycling holidays from Auckland to Tauranga (December 1944) and from Whangārei to Paihia, across to see Tāne Mahuta and

Mollie’s 5th birthday Gwenyth aged 7

back (December 1945). Four years later, “That bike came to Dunedin, basket included,” where Gwenyth found “a bicycle is certainly a necessity” and it “eventually was bequeathed to my friend Alison at the Community of the Sacred Name in Christchurch.”

Another abiding childhood memory was her father singing songs on Sunday evenings. A particular favourite was “Two Little Girls in Blue,” Charles Graham’s sentimental 1893 music hall ballad about two sisters who (like Will’s elder sisters Nell and Dolly) married two brothers.

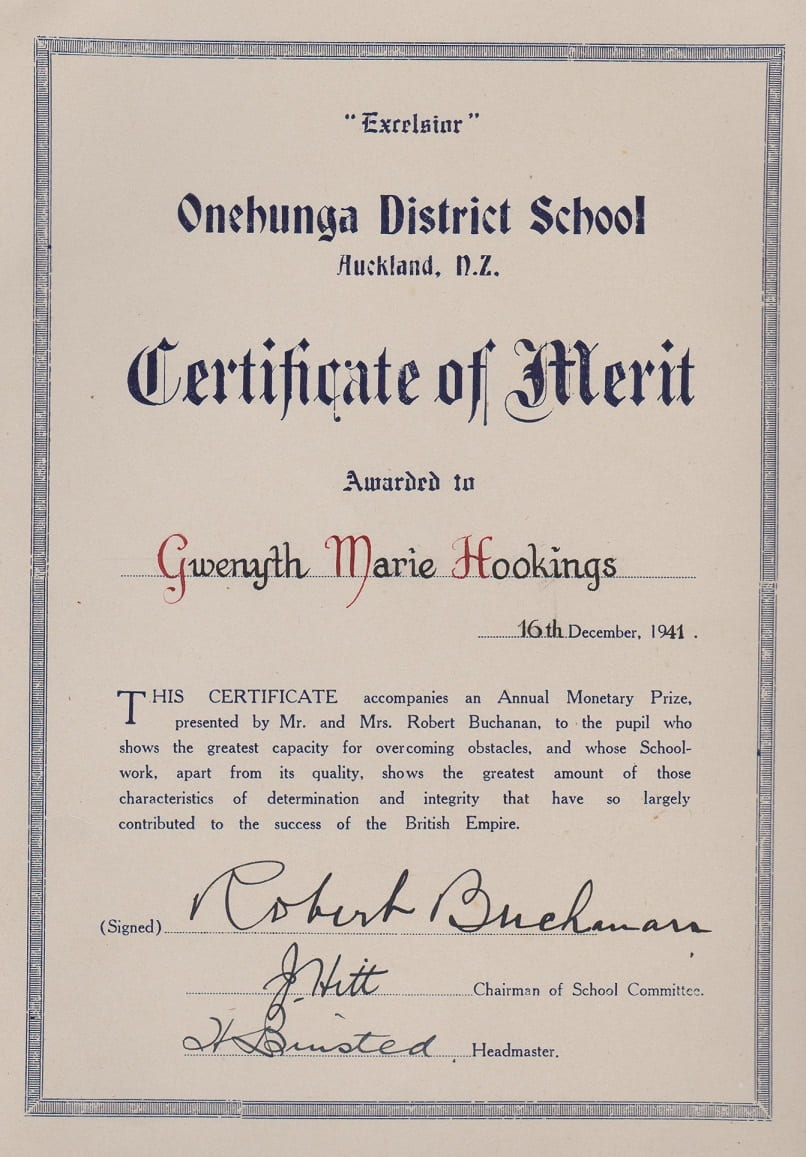

Gwenyth followed her older brothers to Onehunga Primary School where, like them, she excelled. All three siblings in turn won the Buchanan Prize, endowed by a local butcher, Robert Buchanan, and awarded annually to “the pupil who shows the greatest capacity for overcoming obstacles, and whose Schoolwork, apart from its quality, shows the greatest amount of those characteristics of determination and integrity that have so largely contributed to the success of the British Empire.”

Career aspirations

Gwenyth won this prize at the age of 12, in December 1941, before going to Epsom Girls’ Grammar School the following year. By then, she and her family did have a formidable obstacle to overcome. As Gwenyth recalled it years later, her father suffered a breakdown, which she remembered was caused by British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain’s declaration of war on 3 September 1939.

Whether the 10-year-old Gwenyth’s memory of the timing of this traumatic event was accurate (her sister Mollie was not able to confirm this account in later years), correspondence from the Medical Superintendent of the Auckland Mental Hospital confirms that Will was admitted in May 1942 due to “melancholia,” and remained in hospital, suffering from chronic depression, for 10 years until his death in 1952.

Brother Alan recalled (in a family history project by his granddaughter) (4) that when it became apparent that his father would not recover, the bank helped Alice and her family move in 1943 to a house in Yattendon Road, St Heliers. She would take a long journey by tram, at least once a week, to visit her husband in the hospital (now the Unitec Institute of Technology) in Mount Albert.

Gwenyth’s teenage experience of visiting her father was apparently the basis for her decision to attend medical school. She described seeing important-looking gentlemen in white coats who were helping the patients. Asking how she could become one of those, Gwenyth learnt they were psychiatrists and was told that she’d first have to complete medical school before specialising in psychiatry. That indeed became her career trajectory. When later asked why she chose to become a doctor, Gwenyth simply replied that she “wanted to help people.”

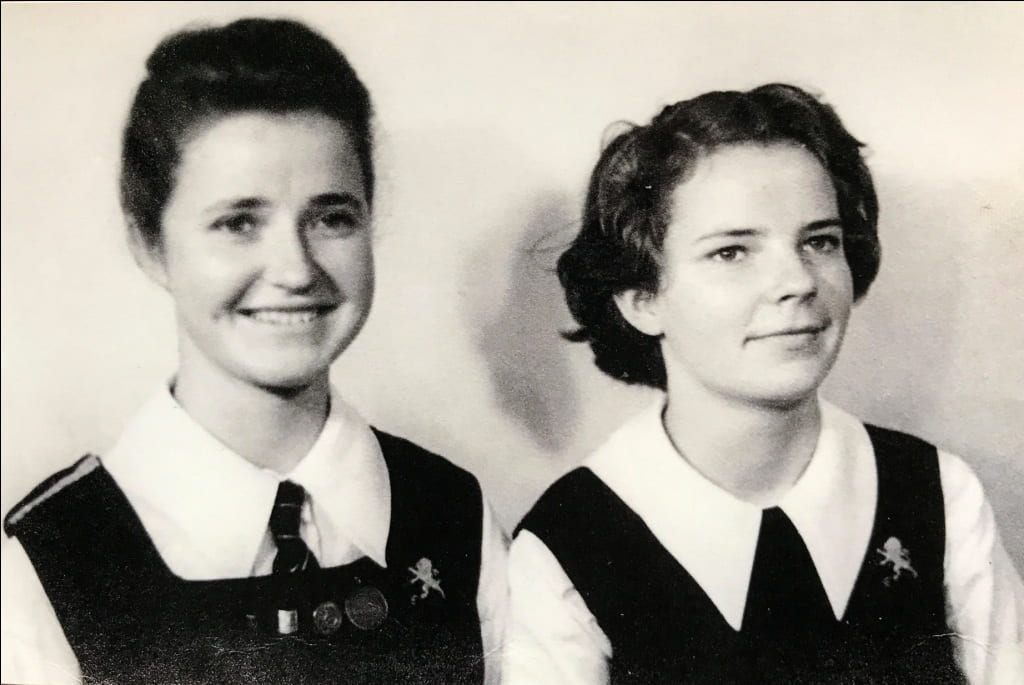

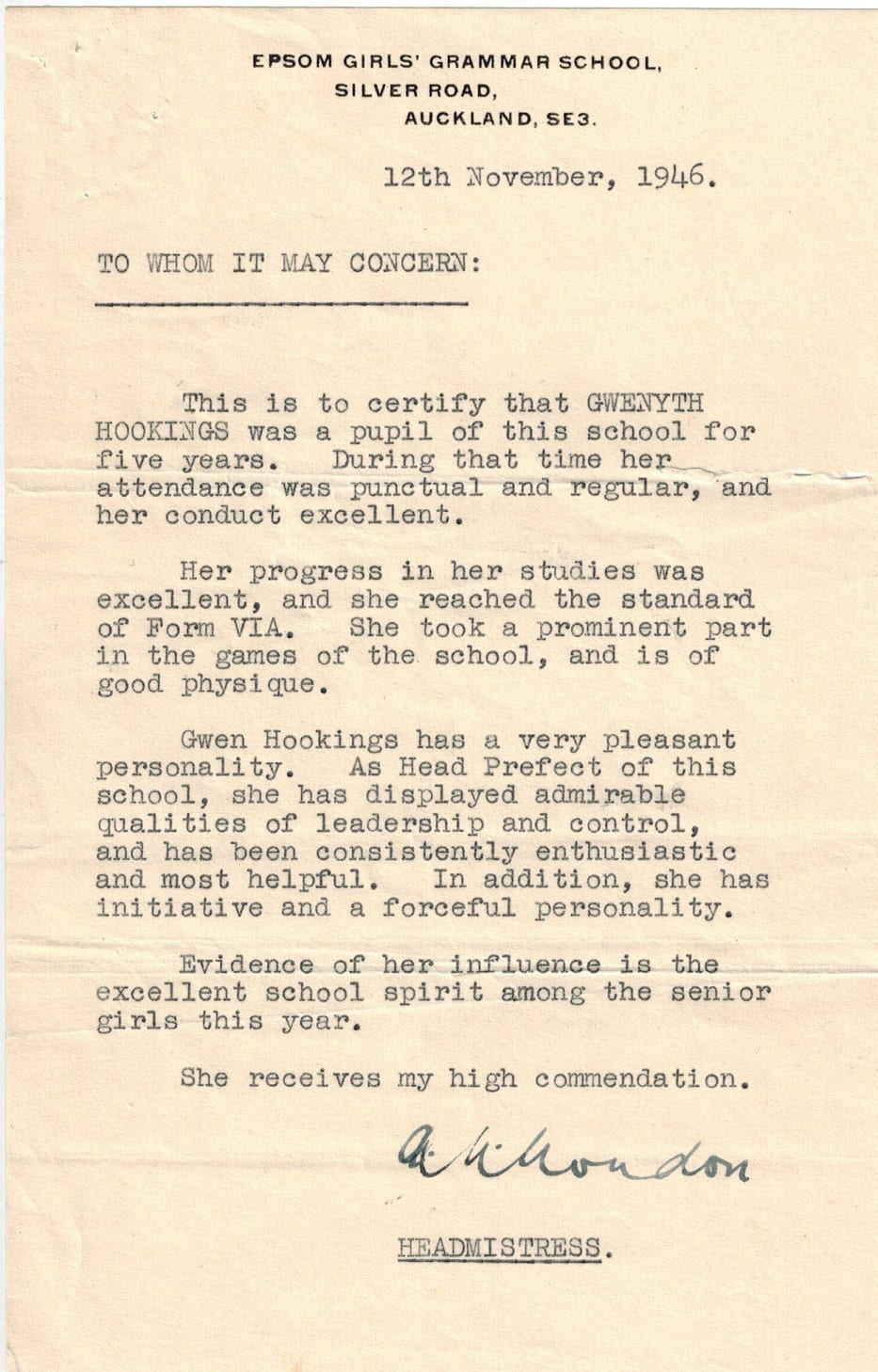

Gwenyth attended Epsom Girls’ Grammar from 1942 to 1946, later recalling matter-of-factly: “Naturally I never told my schoolmates that my Dad had gone berserk.” Instead, she concentrated on excelling academically, receiving a scholarship in her final year, and prizes for mathematics and for being Head Prefect. In a 1946 letter of reference, headmistress Agnes Loudon wrote: “As Head Prefect of this school, she has displayed admirable qualities of leadership and control, and has been consistently enthusiastic and most helpful. In addition, she has initiative and a forceful personality.”

Years later, Mollie confirmed this latter opinion, when she laughingly mentioned that her strong-willed elder sister was known as the “bossy one” – an epithet Gwenyth did not appreciate. Her classmate Colleen “Anne” Hall (née Conyngham), later remembered: “She was such a close friend all the way through Epsom Grammar where of course she was a Prefect and then Head Girl – very popular and good at everything. Gwen came on lots of summer holidays with us especially to Waiheke Island, and also lived in St. Heliers as we did. I of course continued to know her at Uni and subsequently as a doctor and fellow psychiatrist.” In later years, Gwenyth delighted in visiting Anne at her home in Ōkārito on the West Coast.

An undated letter of reference from the Shortland Street office of the National Mutual Life Association of Australasia suggests that Anne’s family offered practical help to Gwenyth too. District Manager G.S. Conyngham wrote: “She is an outstanding girl with a very fine character & marked qualities of leadership as well as high scholastic abilities. […] Her wide range of interests & her enthusiasm & efficiency qualify her for almost any position, but I feel that her chosen career of medicine is one for which she is particularly suited.”

Medical school challenges

Getting into medical school, however, was another obstacle that required the determination Gwenyth’s teachers had noted. She and her future brother-in-law Geoffrey Dodd (whose sister Margaret married Gordon in 1960), were both studying Medical Intermediate at Auckland University College in 1947, but both failed to make the grade. They followed their teachers’ advice to retake the year. Gwenyth explained that her “physics marks went up two marks, but that was still not good enough to get into medical school.” Like her friend Anne Hall, she also found herself blocked by the large numbers of returning servicemen, who had preferential entry.

Her mother later praised Gwenyth for showing “what some perseverance can do – I’m glad you did not let Dr. Stallworthy’s discouragements about getting into medical stop you at the outset – of course we must give him credit that he did not know then about a bursary to help you through.”

When she learnt that she had finally been accepted, while passing through Dunedin during a South Island holiday in January 1950, Gwenyth wrote to Alice: “This is the most exciting day in my life! I couldn’t believe my eyes when I opened the epistle from the University of Otago in the P.O. this afternoon.”

Like so many students, she needed to work during the holidays to supplement her bursary: “My immediate requirements are a suitable microscope […], a half set of bones, a set of dissecting instruments, plus £26-3-6 fees for half the year!” Gwenyth was planning to pay for those items, plus the obligatory physician’s white coat, out of £50 inherited from her maternal grandmother, “and live on my bursary & what I earn in the hols.”

From Dunedin, she and a friend continued their hitch-hiking tour to Queenstown, where they found work “housemaiding and waitressing” at McBride’s Hotel. Gwenyth explained, “it’s really not hard work – it’s just that I’m not over-keen on bed-making, vacuuming, polishing etc.” She was glad to move on to the “first-class” White Star Hotel where, she later recalled: “We looked quite elegant in our smart white uniforms.” Later that year, Gwenyth would wear a different outfit, a full nursing uniform including veil, when she started working as a part-time nurse at Ashburn Hall, the private Dunedin clinic where she would later serve as a psychiatrist. (5)

Her busy summer over, Gwenyth returned to Dunedin in early March 1950: “Introduction to Med School was very efficient on Friday – straight into a lecture in the afternoon. The introduction to dead bods on Sat. morning in the dissecting room wasn’t nearly as upsetting as expected. We landed the most attractive looking one – not as scrawny as many, but now we find all his fat makes our dissecting a horribly greasy job – however he doesn’t smell as high as some – yet!”

The following week, Gwenyth attended “my first post-mortem – unofficially, of course, for we don’t have to go until 4th year, but I saw no point in putting off the evil hour – was quite keen in fact to see how I’d react. Surprisingly unemotionally actually, despite all the gore.”

She initially lived at St Margaret’s College on campus, where she quickly made new friends and settled into her study routine, reporting a fortnight later that even an invitation from “Miss Barron, the warden” to dine at “the high table” was bearable:

“It’s usually regarded as a bit of an ordeal, but on Thursday there was an English guest from the Federation of University Women – a very delightful person sitting opposite me, so I didn’t have to make conversation with the Baron, but thoroughly enjoyed listening to that of the guest & young, attractive Dr. Naylor (Botany Ph.D.) who has just come out from England to a position here, & lives in at St. Mags as assistant Bursar.”

The following weekend, Gwenyth turned 21, celebrating on Saturday night by taking a group of friends to see a “most thought-provoking and conversation-stimulating” film, “Lost Boundaries” (starring Mel Ferrer as an African-American doctor “passing” as white), before returning to “St. Mags” for a “delicious supper” party. Earlier that day: “Instead of dissecting all morning,” the new medical women and teaching staff were treated to “a most delectable savoury morning tea […] by the 3rd year Women. – Quite a tradition evidently and a most enjoyable gathering.”

That afternoon: “We’d been persuaded that it was poor sportsmanship for the med girls not to put a relay team in the Inter-fac relay at the Athletic sports.” Gwenyth’s group did not expect to do well “against Phys. Eds. etc. but it was a little nerve-racking finding I was 50 yds behind the rest of the field at the end. However we caused some amusement by carrying a humerus as our stick.”

Alice sent Gwenyth a pendant she had received from her parents on her 21st: “To give the ‘Key of the door’ to our children as each one reaches this milestone seems a big thing for mothers to do, even altho’ we do it gladly, & with hope they will benefit from seeing mistakes we made & will in their turn leave the world in a bit better state for having been here.”

Gwenyth replied: “Certainly as an example of self-sacrifice, kindness and sweetness you are the dearest mother any girl could have. I do pray that I may learn to be more like you.” She confessed that this was: “The first time I’ve felt homesick,” and promised to heed Alice’s advice, “for I do know that it is to God, through you, my brothers & sister, and my friends that I owe all my happiness and opportunities that lie ahead for such an interesting life of service.”

During her third year in Dunedin, Gwenyth faced another significant challenge when her father died from bronchopneumonia in May 1952, a fortnight before his 58th birthday. In a letter of condolence, her Aunt Dolly (Charlotte Poolman, née Hookings, 1882-1969) shared memories of her brother: “Mother & Dad were always so proud of their ‘Youngest’,” and she assured her grieving niece:

“His illness I’ve never been able to understand, but I remember his life & work before his illness, with loving pride. Ten years is a long time out of your life. Your memories of your father will be so young. But he was always so hard-working, so honest, & honourable in all his dealings, so trustworthy, so in demand for all kinds of church work. You can be very proud of him my dear.”

The following summer, Gwenyth’s prospects brightened when she met a young survey cadet named John V. Allison (1931-2021). Given her love of the South Island landscapes, it was fitting that she should meet her soulmate on a tramping trip in the Wilkin Valley near Tititea/Mount Aspiring. The river was swollen, and John and his mates helped Gwenyth and her friends across. As Gwenyth later recalled, she heard a beautiful, cultured voice behind her and turned around to see John, a graduate of King’s College in Auckland.

John was equally smitten. During a second trip to the Matukituki Valley at Easter 1953, they bonded over a shared love of reading, music and mountaineering, and were soon deeply in love. By early 1954 he told her, “you have filled my cup to overflowing, you have made me rich beyond all price. […] I am so glad it began there amongst the hills which you know and I know and love so well.”

Early career and anaesthesiology

After graduating with her MB ChB in 1955, Dr Hookings began her career in 1956 as House Surgeon at Ashburton and Auckland Hospitals and specialised in anaesthesiology. Having earlier dropped out of studying classics at Otago University, John was inspired by Gwenyth’s choice of career to abandon surveying and apply for medical school himself. He began Medical Intermediate in 1955, completed a BMedSc in physiology in 1958 and graduated with his MB ChB in 1961.

By February 1957, Dr Hookings had broken off their long-distance relationship, but by January 1958 they were reconciled, and she hinted: “I have been thinking what a wonderful idea it would be to get married in May.”

That prompted John to make a very important phone call from Dunedin on 4 February 1958, when his landlady urged him to pick up the phone and propose. Afterwards, John wrote: “Needless to say I needed no further excuse to ring you to-night – and gee I’m glad I did so for life grows happier every minute. […] Funny thing is that I’d quite decided that it would be a perfect time to pop the fateful question.”

As Gwenyth recalled in December 1996: “We are all grieving the death of (81-year-old) Cecily Buchanan. She persuaded John to ring that evasive girl in Auckland and ask her to marry him. Where would we have been without Cecily?” Gwenyth and John were married for just under 59 years.

At the time of their wedding, Dr Allison was an Anaesthetic Registrar at Auckland Hospital, and was featured in a Woman’s Weekly article “Inside an Operating Theatre.” (6) The two-page spread featured candid photographs and a pithy introduction: “With movies portraying an operating theatre as a seething hive of heavy drama, curt commands, and fainting medical students, and popular books dismissing it all as merely a handy place for holding reviews of ‘the night before’, it was a relief to discover that in real life, New Zealand at least, adopts a happy medium.”

The caption to a picture of Gwenyth in scrubs explained: “Another important member of the team – the anaesthetist – is shown here assisting the patient’s breathing by means of a bladder-like apparatus.”

Continuing her career as Anaesthetic Registrar at Dunedin Hospital (1959-1960), Dr Allison paused briefly to welcome her sons Peter (in Dunedin, 1960) and Anthony (in Epsom, 1961). The day after Peter’s arrival, Gwenyth wrote home:

“Once it’s over, there’s really nothing to having a baby is there? (Aha, I hear you mothers say – just you wait.) […] The main thing is that I get to know how to deal with the little chap as soon as possible so that we can settle in to a good routine for me to return to work.”

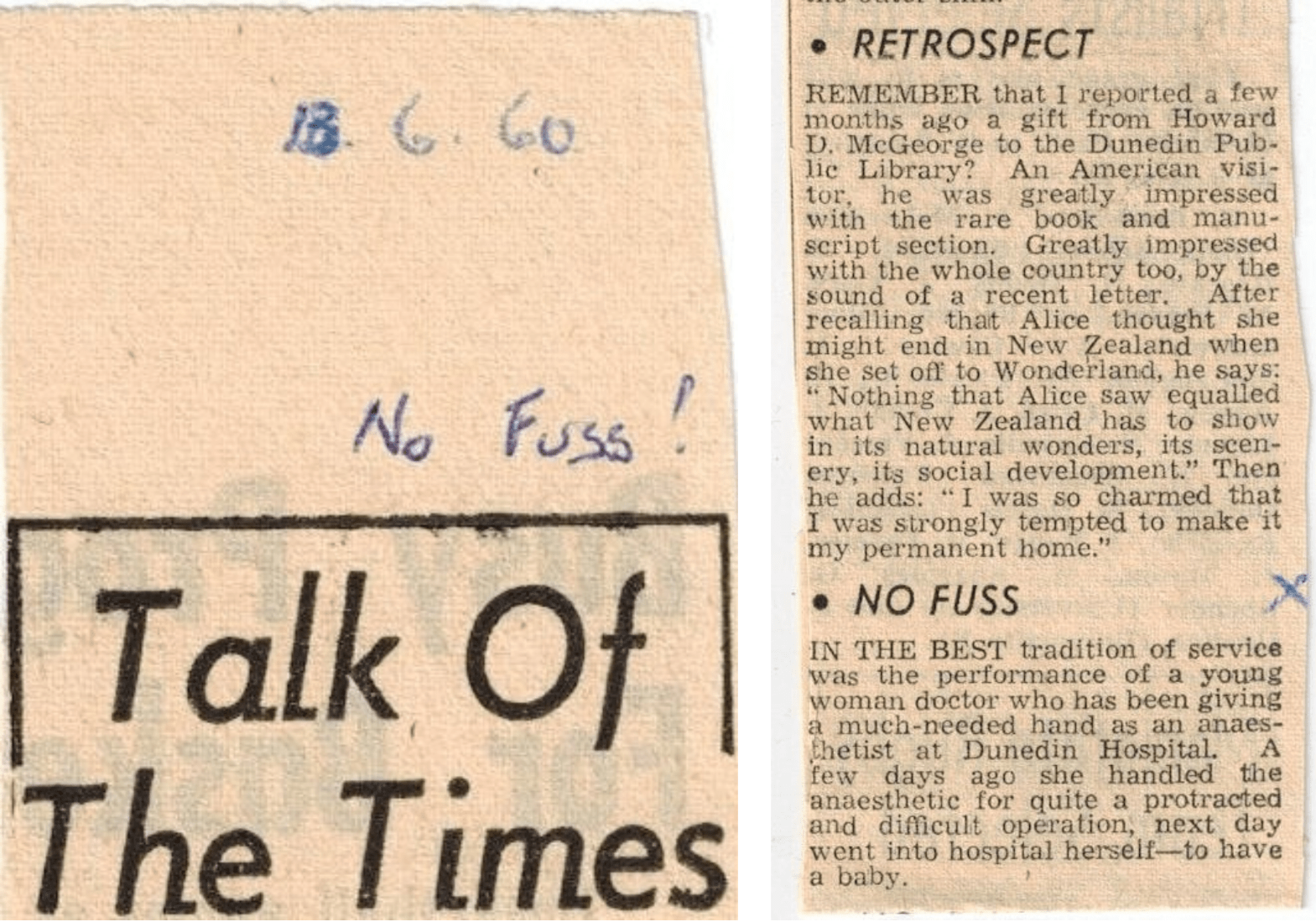

The following week, the Otago Daily Times published an amusing anecdote in its “Talk of the Times” column, which Gwenyth cut out and annotated with “No fuss!”:

“NO FUSS

In the best tradition of service was the performance of a young woman doctor who has been giving a much-needed hand as an anaesthetist at Dunedin Hospital. A few days ago she handled the anaesthetic for quite a protracted and difficult operation, next day went into hospital herself – to have a baby.” (7)

While raising her young children, Dr Allison continued working part-time as a Visiting Anaesthetist at Dunedin Hospital from 1963 to 1967, and did anaesthetic work in private practice, in partnership with her 1955 classmate Clarice Lora “Betty” Main (née Moore). In 1965, she began working part-time as a Student Health Medical Officer at the University of Otago, while also studying psychology at the university.

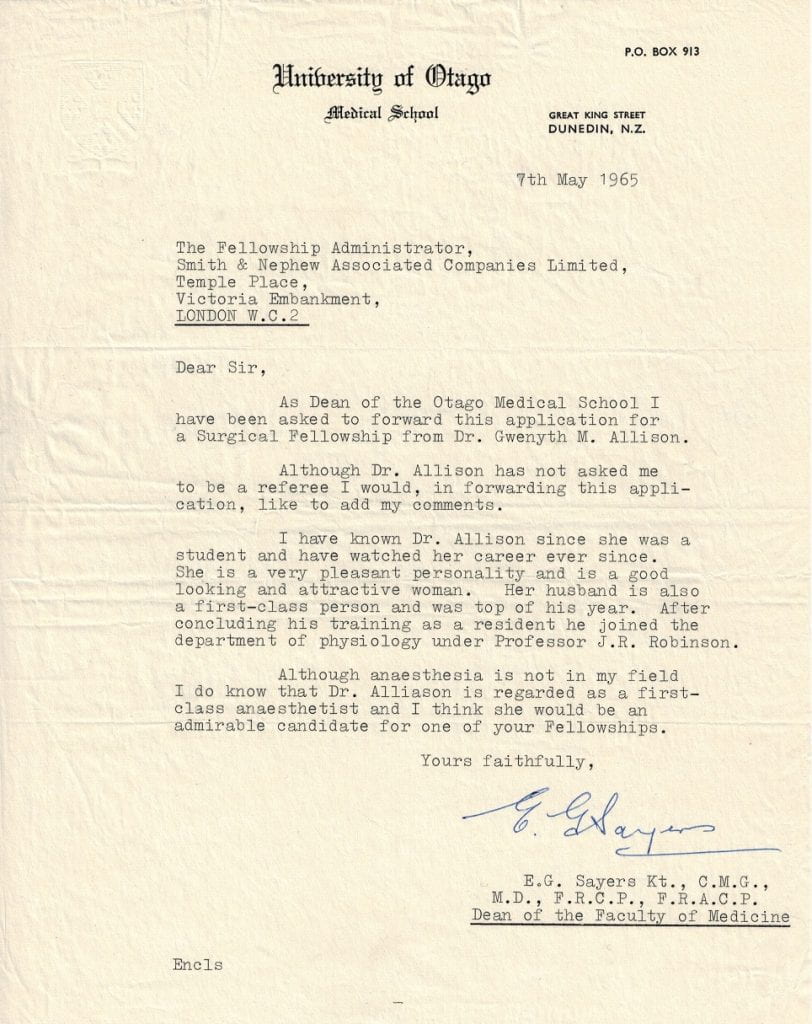

Gender challenges

As a matter-of-fact, no-nonsense medical woman, Gwenyth’s sons do not recall her ever complaining about the challenges of being a female doctor in a largely male profession. Yet an unsolicited 1965 letter of reference from the Dean of the Otago Medical School speaks volumes about the pressures she faced. In 1964, John had been awarded a fellowship to continue his physiology research in London, and Gwenyth also applied for a fellowship there. In his letter, Sir Edward (“Ted”) Sayers chose to add some striking comments in support of the candidate’s application:

“I have known Dr. Allison since she was a student and have watched her career ever since. She is a very pleasant personality and is a good looking and attractive woman. Her husband is also a first-class person and was top of his year. After concluding his training as a resident he joined the department of physiology under Professor J.R. Robinson.

Although anaesthesia is not in my field I do know that Dr. Alliason [sic] is regarded as a first-class anaesthetist and I think she would be an admirable candidate for one of your Fellowships.

Yours faithfully, E. G. Sayers Kt., C.M.G., M.D., F.R.C.P., F.R.A.C.P. Dean of the Faculty of Medicine”

When family members later found this document, John recalled that the first letters after this formidable physician’s name (Knight Commander of St Michael and St George) were known to waggish Otago medical students as: C.M.G. (“Call Me God”) or alternatively K.C.M.G. (“Kindly Call Me God”). A much more rare honour, allegedly, was the G.C.M.G. (“God Calls Me God”).

Travels to the UK and back to New Zealand

Whatever professional challenges both Doctors Allison faced, they had found in each other an ideal ally and sounding board to help cope with them. Gwenyth and John’s evening ritual, for many years, was to sit down together before dinner and discuss the ups and downs of their day over a glass of dry sherry.

When the family moved to London in late 1967, John flew ahead to start work in the Haematology Department at St Thomas’ Hospital, while his wife and sons followed by ship. During their eight-week separation, John sent his airmail news to Gwenyth, clearly missing her wise counsel and instant feedback as he coped alone with the culture shock of settling into a demanding job in a major British teaching hospital, navigating a vast, expensive and unfamiliar city, and finding suitable accommodation for his family:

“London is an infuriating, delightful, disorganised, cold, beautiful, mad, DIRTY jumble & takes HOURS to get anywhere but fun,” because it was also “full of fascinating shops & sights & people when you have the leisure to enjoy them.”

Gwenyth sympathised and insisted the move was, “NOT A MISTAKE. It is up to us to make sure that it isn’t – that despite adverse circumstances we can contribute to life to the best of our ability.” Later, in mid-voyage, she added: “I do feel we’re starting life in this big tough world very late – we do want to enjoy every minute of it – even the bad bits – so away with as many inhibiting factors as possible.”

John assured her, “you’ll love it once you’re doing what you want, for with your capacity for people – there will be lots & lots to keep you going & if ’tis psychiatric wise you tend I’m sure there’ll be much scope!”

That prediction proved accurate. In 1968 Gwenyth worked part-time as a Student Health Clinical Assistant at University College and St Mary’s Hospital, then held locum appointments in the Drug Dependency Units at Lambeth, Middlesex and Bexley Hospitals. But from 1969, tending towards her goal of specialising in psychiatry, Dr Allison served as a part-time Psychiatric Clinical Assistant at Goodmayes Hospital, Essex.

In 1971, the family moved back to Dunedin. While John returned to the Physiology Department and continued the research that led to a PhD in 1975, Gwenyth resumed her role as Student Health Medical Officer at Otago University, and from 1972 became a Registrar in the Department of Psychological Medicine. She completed her postgraduate Diploma in Psychological Medicine in 1977, with a thesis on “Student Health and Examination Stress.” (8)

Dr Allison subsequently worked for many years as a consultant psychiatrist at Otago’s Ashburn Hall, Cherry Farm and Wakari Hospitals, and served as Senior Registrar and later Clinical Lecturer in the Department of Psychological Medicine.

In March 1981, she revealed some of the challenges of her professional life, when she told a colleague about her decision to “leave my two half-time jobs at Ashburn Hall and the Outpatient Dept. of Psych. Med. and plunge into the hurly-burly of Cherry Farm. […] Needless to say I am somewhat apprehensive about yet another major life change but the die is cast.”

Acknowledging a “chronic affliction of feeling less than adequate in my role as a ‘specialist’ psychiatrist,” Dr Allison added: “The one sphere in which I do cope reasonably well is as visiting psychiatrist to Balclutha Hospital twice a month. Being thrown entirely on my own resources I have to get by, and really enjoy the intrigues” of the South Otago community.

John became a Senior Lecturer at Otago Medical School and later Associate Dean of Student Affairs. He and Gwenyth took advantage of his eligibility for sabbatical leave by returning twice more to the UK. In 1979, Gwenyth worked as a Clinical Psychiatric Assistant at St Bernard’s and Sutton Hospitals, and in 1986, she became a Clinical Psychogeriatric Assistant at West Suffolk Hospital, in Bury St Edmunds.

In the latter 15 years of her career back in Otago, Dr Allison continued to specialise in geriatric psychiatry and dementia care. One memorable incident occurred in February 1993, when she broke her ankle after being pushed over by an elderly patient at a Senior Citizens Club meeting. By April she cheerfully reported: “At long last I’m out of plaster and my ankle is being tortured three times per week by the physiotherapist.” Later, Gwenyth and two friends who were recovering from similar injuries formed a Broken Ankle Club, meeting weekly for coffee while their bones continued to mend.

Working through retirement

Dr Allison continued working well past her “official” retirement in 1996. She observed, “This being ‘half-retired’ is not very satisfactory but I guess it’s better to be having work as occupational therapy (and payment!) than knitting or Backgammon.” Six months later, she again expressed her ambivalence: “Retirement? i.e. Not needed with my years of medical & psychiatric experience ever again? What a waste. I quite envy those who die in harness.”

Three years later, she “retired” again “with little regret this time.” Asking pointedly, “And what am I doing to justify my existence after the prescribed ‘three score years and ten’?” she answered with typical briskness: “Being useful to someone.”

In June 2000, she made one last “locum commitment at the Psychogeriatric Service,” and was glad once again to be “preoccupied with my elderly patients.” Finally, in January 2001, two months before her 72nd birthday, she announced: “I am now a non-working woman – a relief, but the 7-month part-time locum was a great distraction.”

The urge to be “useful to someone” nonetheless continued, as microbiologist Sean Davison noted in “Before We Say Goodbye,” his searing 2009 book about “euthanasia and the hunger strike of a cancer-stricken GP.” (9) His mother, Dr Patricia Ferguson, almost 85 and suffering from secondary cancer, had expressed her desire to end her life. In 2006, Sean met her friend who, like Pat, was “a retired psychiatrist”:

“Gwenyth spent her days going from one old lady to another, taking them out for their walks. It has become her mission in life to help these elderly people in their twilight years. Mum was analysing her role in Gwenyth’s life at the time, and concluded that she wasn’t one of her ladies who needed the exercise and the company, but instead needed a friend to have a chat and lunch with.”

As was typical for Dr Allison: “We then arranged for lunch to be at the same café at the same time every Thursday. I’ll be able to go off for a swim, while she and Mum chat about Gwenyth’s rambles. Yes, I admire Gwenyth for the job she does, walking all those old ladies. It really can’t be that much of a pleasure for her.”

Dr Davison later thanked Gwenyth “for bringing so much pleasure to my mother’s life. She loved her Thursday appointments with you. Such seemingly small things are so very important towards the end. You are an angel to so many people.”

Dr Allison continued leading walks in and around Dunedin for the Phoenix Club, an exercise and rehabilitation group for recovering heart patients. The Botanic Gardens were always a favourite haunt, and she and three friends, Shirley Callachor, Roberta Highton and James Hannah, sponsored a bench in a secluded spot with a panoramic view over the city.

Having assisted so many patients with eldercare issues for so long, it was a cruel irony when Gwenyth herself was diagnosed with dementia in 2012. She was admitted to St Andrew’s Home and Hospital in Dunedin, where she died peacefully on 14 January 2017.

“When you’re hot & parched & famished, just take a look at Raspberries & cream!”

Family life and hobbies

In her student years, Gwenyth developed a particular love of exploring the South Island on foot and by hitch-hiking during lengthy trips, which she chronicled in a series of “letter-diaries” home to her mother and siblings. “There’s no doubt about tramping being really the best way to see the country” she declared in 1950, as she and her friend took every opportunity to explore the Wakatipu area, including the Routeburn, through the Homer Tunnel, still under construction, to Milford Sound, and two ascents of Ben Lomond:

“Our sun-rise view from the top of Ben Lomond did give Betty & I a tremendous panorama of range after range, and snow-capped peaks one after another, but now that I have tramped among them, climbed some, looked down upon a few and gazed up at the many, that first passion for the mountains is stirring in my bones.”

The young medical student pursued that passion at every opportunity, joining the Otago Tramping Club for weekend excursions, and later the New Zealand Alpine Club. A year later, at the end of another lengthy trip hitch-hiking and tramping down the West Coast and over the Haast Pass to Wanaka, and then up to the Hermitage Camping Ground, Gwenyth enthused:

“I can hardly believe this is really me – sitting here with the sun rising on Mt Cook, & even more gloriously at the moment on Mt. Sefton. To think that one girl should see so much of glory in one holiday is just not fair, when others spend days in the mountains & get rain & cloud all the time.”

On 4 January 1954, Gwenyth and John were climbing with an Alpine Club group on the Murchison Glacier side of the Tasman Saddle, with the aim of summiting Mt. Aylmer. Gwenyth slipped on icy snow, and began “sliding down the slope feet first. She made an effort to brake her slide with the pick of her ice-axe, but this was wrenched from her grasp.” (10) She continued sliding for 200 feet and disappeared into a crevasse.

The party’s leader Carl Bullivant, a fellow medical student, “immediately doubleroped into the hole,” which was “15-20 feet deep,” where he found that the victim had fractured her left leg and forearm. While he stayed to administer first aid, John and other climbers went to seek help. After sheltering overnight in a snow cave, and then in a nearby hut during continued bad weather, rescuers brought the injured woman down to Timaru Hospital three days later. (11) Thereafter Gwenyth and John generally preferred tramping, rather than high alpine mountaineering.

Dr Allison took the challenges of being a working mother in her stride, enlisting friends, and later hiring part-time housekeepers, to help with childminding in the early years. In Dunedin, she and John instilled in their sons a love of Otago landscapes, with regular tramping trips up Flagstaff, to the Taieri and beyond.

Moving to the UK was an especially formative influence. Living in southeast London, with Greenwich Park within walking distance across Blackheath, the family enjoyed the excitement of life in the capital. In their VW Beetle, they took every opportunity to visit stately homes and museums, exploring the countryside from Kent to the Lake District, and mountains from Snowdonia to Skye.

Back in Dunedin, while juggling the demands of her career and studying for her postgraduate diploma, Gwenyth always found time for swimming and tramping. Memorable holidays included hiking the Routeburn Track, skiing at Coronet Peak and exploring a Roxburgh sheep station owned by relatives. A keen swimmer all her life, Gwenyth was a weekend regular at Moana Pool and took any opportunity to go surf swimming at beaches around the country.

A passionate lover of travel, Gwenyth was always glad to explore new places and revisit old ones, especially the homes of her extended Auckland family, to catch up with her siblings, her many nieces and nephews and their families. In later years, nothing gave her greater pleasure than spending time with her two beloved granddaughters in Auckland: She and John regularly visited son Peter, daughter-in-law Micheala and their daughters Bridie and Fritha. She was glad when son Tony and daughter-in-law Tammy were able to visit from Las Vegas.

Gwenyth would often while away spare moments at airports or in-flight by writing letters. In 2003, she noted: “At 7:45am floating above the Tasman en route to Cook Strait & Golden Bay […] I am suspended between the Auckland family and Dunedin husband and friends with bated breath.”

A gregarious and sociable woman, and a famously prolific snail-mail correspondent, Gwenyth assiduously kept in regular touch with a vast circle of friends and family members all over the globe. Her letters were full of news of her travels throughout New Zealand, across the Tasman and around the world, and her latest discoveries as an insatiable and discerning culture vulture.

Gwenyth’s medical school contemporaries formed the core of this extensive social network, including (EGGS schoolmates) Anne Hall (née Conyngham) and Margaret Maxwell (née Parsonage), as well as Katharine Bowden (née Thomson), Kathleen “Kay” Bradford (née Johnstone), Ross and Iris Fairgray, Robin and Elizabeth “Bunty” Irvine (née Corbett), Brigadier Brian McMahon, Elizabeth Naylor (née Beauchamp), Sam and Rosalie Sneyd (née McPherson), and Senga Whittingham.

She loved showing visitors around her favourite parts of Otago, and sharing her passion for New Zealand’s flora and fauna. One favourite destination was Wanaka’s Glendhu Station, where Gwenyth regularly joined friends on tramps in the Matukituki or Cardrona valleys. In 1995, she wrote: “I do love this place – passionately. […] This afternoon, the clouds had lifted and on a perfect wind-free autumn afternoon I was taken up a new track in the Waiorau Gully emerging on the Roaring Meg saddle with the rocky ridges of the Pisa range surrounding me. My idea of a perfect walk for aging trampers.”

Insatiably curious, Gwenyth read widely, revelled in her garden, and cheerfully admitted to “my radio addiction – and the big screen when there’s something worth going to.” A regular churchgoer, she particularly enjoyed attending Evensong at St Paul’s Cathedral, Dunedin. A lifelong lover of the arts, including music and opera, theatre and dance, film and the visual arts, Gwenyth assiduously attended concerts and film screenings, and visited museums and galleries everywhere she went.

Gwenyth enjoyed regularly meeting her many friends at favourite Dunedin cafés, and attending University of the Third Age classes with John. In 1998, she admitted being “preoccupied with the ordeal of having to present a joint seminar to the U3A group on ‘Aspects of Growing Older’ – the topic ‘Relationships’ – with Roberta Highton […] Such a relief to have it over.”

Retirement years were therefore rich and varied. As Gwenyth noted in October 2000: “I’m very busy with my three half-days/week work […] plus a few walks with people who need me as a ‘walking companion.’ John is flat out as a music student of Harmony – plus post-grad teaching. Life rushes on.”

Inspiring the next generation

In a fulfilling life of 87 eventful years, Dr Gwenyth Allison made a difference in the lives of countless family members, friends and colleagues, and her patients in New Zealand and the UK. Growing up at a time when mental illness was a taboo topic, even this psychiatric professional did not openly discuss the illness that impacted her family, and must have been so traumatic to witness in her youth. With quiet Kiwi modesty, she simply kept busy with overcoming such obstacles.

Gwenyth’s example as one of New Zealand’s early medical women helped inspire other family members to follow her lead. Her nieces Dr Jenni Waddell (née Hookings) and Dr Clare Hookings both graduated from the University of Auckland School of Medicine and became general practitioners in Tāmaki Makaurau. Jenni told family members that she recalled thinking that if Aunt Gwenyth could study medicine, she could too. Clare had “several relatives who were doctors,” including her uncle Geoffrey Dodd and his son Nicholas, as well as Gwenyth and John, and her cousin Jenni, a “couple of years ahead of me. Because of that I thought it was just an ordinary decision to choose medicine as a career. It didn’t cross my mind that as a female it wasn’t so usual. By my time I think nearly half the students were female.” (12)

Bibliography

- This biography is largely based on letters, documents and photographs from Gwenyth’s collection, plus photos and family history research by Dr Jenni Waddell and family, Margaret Mattson and family, and other Hookings family documents.

- Gordon Hookings (2001) “Memories,” unpublished memoir, courtesy of Hookings family.

- This and all subsequent quotes from Gwenyth’s letters and other correspondence are from the family’s collection.

- Elise Waddell (2004) “Alan Hookings: Living Historian,” family history project, courtesy of Waddell family.

- Cameron Duder (2007) “The Ashburn Clinic: The Place and the People,” Dunedin, The Ashburn Clinic, p.60.

- The New Zealand Woman’s Weekly, 5 May 1958, “Inside an Operating Theatre,” pp.14-15.

- Otago Daily Times, 13 June 1960, “Talk of the Times: No Fuss.”

- Gwenyth Allison (1977) “Student Health and Examination Stress: A review of the literature and a pilot investigation at the University of Otago,” thesis submitted for Postgraduate Diploma in Psychological Medicine, University of Otago, Dunedin.

- Sean Davison (2009) “Before We Say Goodbye,” Devonport (Auckland), Cape Catley Ltd., cover, pp.20, 30-31; (spelling “Gwyneth” corrected).

- Carleton M. Bullivant (1954) “Report on Tasman Saddle Accident – January 1954,” (unpublished).

- Christchurch Star-Sun, 5 January 1954, “Rescue Parties Now Bringing Out Woman Injured in Mountains,” p.3; The Press [Christchurch], 6 January 1954, “Girl Climber Injured: Rescuers Reach Scene: Party Now in Malte Brun Hut.”

- Dr Clare Hookings, e-mail, 1 November 2021.

__________

Captions

GMA01 Gwenyth M. Hookings MB ChB, 1955

GMA02 The Hookings family, 28 October 1934, Onehunga, Rear: Gordon (14th birthday), Alan (12) Front: Gwenyth (5), Will, Mollie (3), Alice

GMA03 “Two Little Girls in Blue,” 15 August 1936, Mollie’s 5th birthday, Gwenyth aged 7

GMA04 Buchanan Prize Certificate, 16 December 1941

GMA05 Epsom Girls’ Grammar School c.1946, Gwenyth and Mollie

GMA06 Agnes L. Loudon MA DipEd, 12 November 1946

GMA07 Alice Mary Coward c.1912

GMA08 Alice Hookings’ letter to Gwenyth, 21 March 1950

GMA09 Gwenyth’s reply to Alice, 26 March 1950

GMA10 Gwenyth c.1956-57

GMA11 Medical Graduates, December 1955, (steps of) St Paul’s Cathedral, Dunedin: Gwenyth Hookings front row, third from left

GMA12 John and Gwenyth Allison, 3 May 1958, Auckland

GMA13 “Inside an Operating Theatre,” NZ Woman’s Weekly, 5 May 1958

GMA14a & GMA 14b Otago Daily Times, 13 June 1960

GMA15 Sir Edward Sayers Kt. C.M.G., 7 May 1965

GMA16 50th Reunion, Class of 1955, Otago Medical School, Dunedin, 19 November 2005

Back row (left to right): John Scott, John Musgrove, Jules Nihotte, Robert Graham, Alan Taylor, Derek Livingstone, Laurie Smith, Brian Barrett, Bill Tucker

Second row: Dacre McKenzie, John Richards, John Werry, Murray Haslett, Ken Mickleson, Richard Thomson, Brian Oldham, Owen Dine

Third row: Brian McMahon, Ray Bernard, Bob Hughes, John Andrew, Bill Treadwell, John Commons, David Palmer, Joe Pope

Fourth row: Graeme Campbell, Gordon Sheehan, Ross Sheppard, Denis Friedlander, Heather Thomson, Margaret Maxwell, Jim Macdiarmid, Joe Brownlee, Barry Colls, Constance Dennehy, Stan Parkinson

Front row: David Wilson, Dick Clark, David Taylor, Tom Farrar, Bill Bird, Neil McLeod, Bron Robinson, Jack Chin, Tony St John, Robin Norris, Charlotte Robertson, Gwenyth Allison, Dick Cartwright

Absent: David Gray

GMA17 50th Reunion, Medical Women, Class of 1955, Dunedin, 19 November 2005

(from left:) Margaret Maxwell, Constance Dennehy, Charlotte Robertson, Gwenyth Allison, Heather Thompson, Bron Robinson

GMA18 Gwenyth tramping c.1952-53, Annotated on back: “When you’re hot & parched & famished, just take a look at Raspberries & cream!”

GMA19 Christchurch Star-Sun, 5 January 1954

GMA20 John, Gwenyth, Tony and Peter, c. January 1962

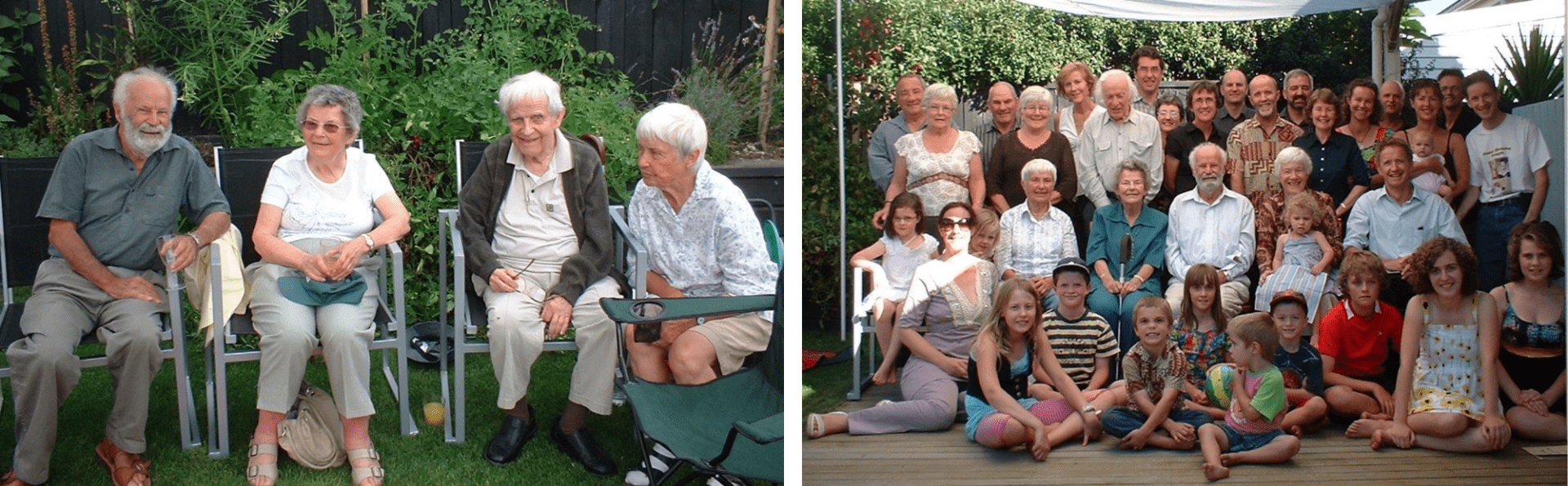

GMA21 Gordon, Mollie, Alan, Gwenyth, Herne Bay, 24 February 2007

GMA22 Whānau celebrating Gwenyth’s 80th birthday, Herne Bay, 29 March 2009

GMA23 Coronet Peak, October 1991

GMA24 St Clair, Dunedin, 28 March 2014

GMA25 Yosemite, California, 1 April 1998