This biography is largely based on Barbara’s own written reflections of her life as well as a zoom interview Professor Cindy Farquhar and Rennae Taylor had with her two daughters, Helen and Hilary Heslop, on 27 March 2023. The biography was constructed by Rennae Taylor. Other secondary sources are listed in the bibliography. All photos were provided by her daughters.

Class of 1948

Contents [hide]

Family History and Childhood

Barbara Farnsworth Cupit was born on 26 January 1923 to John Sampson and Louisa ‘Isobel’ (nee Peppler) Cupit at 97 West End Road, Herne Bay, Auckland possibly under the care of midwife LM Comber who ran her own nursing home on this street. (1, 2) Her younger brother Austin John, born four years later in 1927, chose teaching as his career and resided with his family in Auckland.

Barbara’s mother Isabel was born in Christchurch, New Zealand in 1888 to Augustus and Frances (nee Carston) Peppler. At the time of her marriage, the family was living in North Beach, Christchurch. The Peppler’s had immigrated to New Zealand from Germany and the Carston’s, originally from England, were very early settlers in the Leeston area of Canterbury. Both her mother and maternal grandmother had ‘dabbled’ at Canterbury University. Frances had also done some accountancy qualification and worked in her father’s office, Pepplers Ltd, which was a firm of furniture makers.

Barbara’s father John immigrated from Derbyshire, UK after World War I and married Isabel on 9 November 1920 at the Beach Church, New Brighton. (3) He was the ninth of ten children born to parents who were tenant farmers. His father was a harsh disciplinarian, but he was very devoted to his mother. After her death, contact with his UK family was minimal.

Barbara’s parents made their home in Auckland where John worked as a senior welfare officer for the Department of Child Welfare. The family lived in Epsom during Barbara’s childhood where she attended Epsom Primary and later Epsom Girls Grammar School (EGGS). She enjoyed sports, played hockey during her secondary school years, and enjoyed skiing into her adult years. She recalled she was always bookish and loved classical music. She learned to play on the piano from her grandparents’ home in Christchurch which made its way north to their Auckland home. Her daughters said she was an excellent classic pianist, and their home always had a grand piano.

Childhood Recollections:

My parents had to scratch for my piano lessons – 30 shillings a term in the depression when I was 9. Eileen Slade, my teacher, had been at Melbourne Conservatorium of Music, but was working as a dressmaker in Auckland with a few piano pupils – a typical depression story. I heard Moiseiwitch, one of the great pianists of his day, when I was about 12, and was absolutely thrilled. When we had a radio later, there was always the concert programme etc. The Messiah in the Town Hall later became an annual event.

My parents had talked about sending me to school at St Cuthberts, but it entailed crossing Manukau Rd. I doubt if they could have afforded it. Anyway, the Epsom Primary was just round the corner, and the headmaster later advised EGGS. I think St Cuthbert’s may well be a little better than EGGS today, but it simply wasn’t in the same academic league in those days. Incidentally at a time when not too many girls even got to secondary school, Class 3A at EGGS in 1938 had NZs two first medically qualified professors (Beryl Howie – O&G at the Christian Medical College, Ludhiana, Univ of Punjab, India, and myself) and the first woman superintendent of a metropolitan hospital (Margaret Hoodless (later Wray, now Guthrie), Princess Margaret ChCh.). Nobody would have predicted this in the 1930s, but EGGS was unapologetically academic. I remember the headmistress saying on our first day in the third form that she would expect university scholarships from the 3A class 5 years hence (classes were streamed). It never occurred to me that this was an unusual expectation because my parents thought similarly.

In 1942, Barbara was successful in obtaining her University National Scholarship with the seventh highest score (1483) in New Zealand (4) and then did her first year medical at Auckland University. She recalls learning very little during this year except having her first exposure to genetics (Mendelian) and ‘being hooked’.

In her memoirs Barbara recalled her childhood environment:

Learning Resources in the Home:

For a future NZ academic I was born lucky, although I didn’t fully appreciate this until the feminist “revolution”, when the most vocal women started to bemoan the opportunities that they had not had. I had had them and had taken them for granted. My parents were both “bookish” and we had quite a scholarly home library for NZ suburbia, virtually the complete works of the classical English poets and writers. Nobody else that I knew had anything quite like this. I never had trouble looking up literary references at school – we had them in the house. My mother rated Darwin’s Origin of Species as a favourite book. I had the Children’s Encyclopaedia and all the children’s classics of the day. There was also a big Chambers Encyclopaedia. Not as good as today’s Google, but pretty good for the 1930s and 1940s. And for everything else, I was an assiduous borrower from the local library.

Bits of the German side of things rubbed off on us. My mother spoke fluent and chatty German – it was good enough for Germans to ask her what part of Germany she came from. So, we spoke reasonably “good German” at home, and it always sounded much more “normal” than school French, at which I used to come top, and in which I had a far bigger vocabulary. But Hitler’s Germany and the war effectively drew a line across that. When the Hitler atrocities started to be reported in the papers, it was no longer a good idea for my mother to be a member of the German Club. She swapped it for the Red Cross and was secretary of the Epsom branch. She was assiduous. We had a typewriter in the house …. I picked up my first “hunt and peck” typing from that. It served me in good stead for many years before computers. But apart from the German, she also taught us lots of botany (botanical names, incidentally, which often make more sense than the popular names) and bits of astronomy. We toured the museum and the art gallery at Auckland. Most people’s mothers did not seem to go in for this sort of thing, and in retrospect it was a head start, especially as I was ready to soak it up.

Religion:

My father liked reading history – mainly of ancient Rome and the Church of England (C of E). He had been brought up C of E, endured forced attendance more than once on Sundays, and he had a historical bent. He was very sceptical about religion. We were, however, duly christened in the C of E – it was probably as much a declaration of racial identity as it was a religious gesture. We were British. These were the days when England was referred to as “home” by UK ex-pats like my father, of course, but even by my mother, who had been born in ChCh, and for whom Germany could equally have been claimed as home. I am not sure how the Pepplers ended up C of E, because Albert Peppler and Frances Carston had been married by a Lutheran minister in 1879 – all very Germanic for the English Carstons. My grandmother was only 16 when she married, and he was probably the boss. Presumably she had not yet acquired the authoritative demeanour that she later had as an adult. My grandfather was duly naturalised (and thereby escaped being called up for the German army), and possibly adopted the established religion of his new country. But I don’t think anybody felt very strongly about it.

I was not as steeped in conventional Christianity as were most NZ children of the day….I was never a noisy rebel about this – I just refrained from joining in. I declined to learn the school prayer at EGGS (not that anybody ever noticed), because there seemed to be something wrong with the ritual muttering of it every morning at assembly by 600 (minus 1) schoolgirls, and minus the handful of Jews and the occasional Catholic, who were excused prayers because for some reason they didn’t (weren’t allowed to?) communicate with the protestant deity. The cost of our slightly “different” religious education, was missing out on Sunday school and Bible class, the main function of which seemed to be providing the social contacts of adolescence. Social development took place much later in our generation than it does in today’s young people. Presumably something different today replaces the bible class and church of our day.

Expectations:

It was always assumed that I would go to university – I grew up thinking that it was “what you did” when you finished high school. For most girls it wasn’t. In my primary school days, compulsory schooling stopped at about 12, when one got the so-called proficiency certificate. I think that the kids of those days did emerge from the system reasonably proficient at the 3 Rs – there were fewer diversions from them than there are today. There was a very specifically detailed primary school syllabus, although clearly a little experimentation was allowed. Our headmaster taught a small group of us algebra and French in Form 2. The prefects were obliged to adopt the motto “noblesse oblige” which he translated rather freely as “having a privilege carries a responsibility”. I thought about this at an age when it would otherwise probably not have occurred to me. But in a way, it was emphasised at home – my father always said nobody worked for him – they worked with him.

Plenty of girls finished school altogether after primary school and stayed at home until they got married. They started collecting their “box” at an early age – the household linen that was their contribution to their future home. In retrospect it seems almost akin to a dowry. It was common for girls to be asked “started your box yet?” from their early teens.

Otago University School of Medicine

Barbara believed her father had the greatest influence on her choosing medicine as a career. He would say she could do anything she wanted, and she didn’t question it. In retrospect she believed she was protected from the prevailing social mores. In addition, her mother advised her against getting married too early and without qualifications and getting stranded in suburbia. In 1944, like other non-Otago students from her era, Barbara travelled by train and ferry to Dunedin and made St Margaret’s College her home.

She recalled the atmosphere at school was very studious: ‘there was not much partying when every day the paper had death lists from the armed forces’. Money was tight and food and clothing were rationed so life was lived frugally. She recalled on the first day in her second year at medical school, the late Professor Bill Adams reminding them ‘they were all exempt from military service and that we were never to forget that New Zealanders were dying overseas while we enjoyed the privilege of being students’. (5)

Recollections of university days:

We wore nothing on our bare legs in the Dunedin winter. Stockings were rationed, and while I suppose we could have got thick lisle stockings (these were the pre-nylon days), they made an “old lady” fashion statement. Lisle was regarded as simply not on – uncovered keratin was preferable. Silk was only for “dress up” occasions. Both sexes wore beige cotton gabardine raincoats – they were almost a uniform. Girls did not wear slacks to class in those days. For all that, I can’t remember feeling particularly cold. Our “teenage years” (socially) were to all intents and purposes deferred until our 20s. We had been monumentally retarded socially by the war and depression, but most of us were far younger for our age than are today’s students. The 5th year students had a dinner every year, but it was males only. It persisted this way into the 1960s, I think. Strangely enough we didn’t object – it was just the way things were. I recall holding some office on the medical student executive when I was a staff member in the 1950s (vice patron I think – the vice bit sounds a bit interesting, doesn’t it?) and going to the social function after the dinner was over, for a sort of heterosexual “afters” session.

Barbara recalled only one person in their class owned a car. A permit was required to travel by train more than fifty miles, so she only went home during the summer break. She joined the Otago University Ski Club, and her daughters remember her stories of going to Middlemarch, having to walk to the top, ski down and then walk to the top again. Holiday jobs were not only plentiful but obligatory and university students were ‘manpowered’ into picking fruit, working on farms, nurse-aiding and so on. (5)

There were separate women’s and men’s common rooms with a canteen in between which was located on the ground floor of the Lindo Ferguson building at the medical school. The rooms were barn-like and furnished with enormous deep armchairs with long wooden arms that seemed to be designed for people seven feet tall. Barbara recalls very little real sexual harassment in the medical school of the 1940s but recalled one orthopaedic surgeon who harassed both male and female students. (5)

Barbara ended off her sixth year at Gisborne (6) and was one of seventeen women who passed the finals at the end of 1948.

Most were financially broke on graduation, but ‘nothing compared to the debts of some of today’s students’. (5) She spent her house surgeon years at Dunedin Hospital. They worked long hours, lived as a group on the grounds of the hospital and with their wages of $290 per annum let off steam when not working. After the austerity of the war years, they had great fun.

Early Post-Graduate Years

Following her house surgeon commitments, Barbara became a resident pathologist at Dunedin Hospital as well as teaching in the University of Otago Pathology Department and was successful in obtaining her MD degree in 1954 (7).

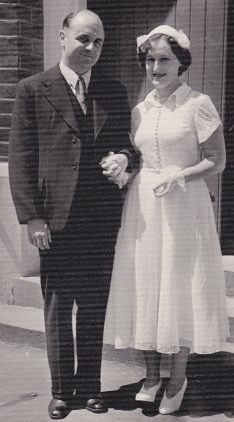

In 1953, she married her husband John Herbert Heslop who was in the class of 1949. In addition to later becoming a surgeon, he was noted for his work with the treatment of burns and became an associate professor in the Department of Surgery at the University of Otago. He was also an avid cricketer; had played for the Otago University club and in later life became involved with the New Zealand cricket administration. Barbara understood the game of cricket and enjoyed watching the matches. They left for London to do post-graduate study at the end of 1953 on the merchant ship, Port Vindex.

On arrival, Barbara began a very enjoyable paediatric pathology research position at Great Ormond Street Hospital which had been organised for her by Sir Charles Hercus, the dean of Otago Medical School, and John continued his surgical training at King Edward Memorial Hospital and the following year successfully completed his FRCS (UK). (8)

The following is Barbara’s recollection of their time in London:

London was still full of bomb sites in 1953. It was a very badly bashed city. Meat was still rationed when we arrived, and the standard of living over-all was substantially below what we had been used to in NZ. Into the bargain we now counted money with extreme care. The London NZ Cricket Club was a social saviour because it organised transport to some delightful suburban and country cricket grounds, with the social addendum of some charming local pubs, and occasionally country houses after the match. We wouldn’t have got to these places as easily otherwise. We were able to ask our friends out for the day to these places, and we all enjoyed them immensely. We used to go to Goodwood Park, the Duke of Richmond’s cricket ground shortly after the Queen had stayed there for the Goodwood races. Not long before we went home in 1956, JH hit a 6 that made a hole in the recently thatched roof of the pavilion, and I was rather worried that we might have to offer the replace it (financially daunting, as thatchers were rare and expensive, and we were not solvent enough to pay for one). JH went back to Goodwood when he was in the UK in 1959 and was asked to try to repeat the big hit. He managed a 6 but not through the thatch.

At the beginning of 1957 they returned to Dunedin where John took up a position of senior registrar and surgical tutor. John was the ship’s surgeon on the return trip, and they were accompanied by ten-day old Helen. Barbara describes their journey back in detail in her memoirs:

Helen arrived 28 November 1956, ten days before we sailed so we went straight from the maternity hospital to the ship in Middlesborough, complete with all the impedimenta of three years in the UK, and a new baby. Staying in hospital for as long as that would be regarded as strange today, but it was the routine then.…Both girls were posterior presentations, and both were forceps deliveries. I had had an episiotomy and had a huge bruise, and it was rather sore sitting on it in a train all day, even though we went first class (such as it was in those days). We had to change trains in Yorkshire. We got to Middlesborough on a dark afternoon on about December 7. Maybe the town had some nice parts, but we didn’t see them. It all seemed incredibly gloomy. In the post-war years it could have served as a film set example of bleakness. Ports had received more than the usual share of bombs. Our cargo ship with twelve passengers, the Port Phillip, was pale grey and white and was the only piece of the scenery that was other than dirty grey.

I had organised a supply of disposable napkins, which were not very common at the time, and they were to be delivered to the ship by Boots. Failure to deliver orders was par for the course in the UK in those years, but it was devastating not to have the napkins. Our supply was, otherwise, to put it mildly, less than adequate. We didn’t sail for another day, so JH had to go into town and get what he could at the local Boots. They had not received the supply from London, but he managed to buy out their stock, and we had just enough to get to Auckland. We stowed about 30 packets of napkins (“Paddipads”) under the bunk in my cabin (JH was in “crew” quarters as ship’s surgeon). We ran straight into an Atlantic gale, and the crew (not JH) had to lash the cot to the wall in the cabin. But they couldn’t lash the 30 packets of napkins, and every time the ship rolled one way, the packets all came out. When it rolled the other way, they rolled back (or some of them did). We spent two or three days awash with them. HEH slept through most of the trip. The sea does a great job as a permanently rocking cradle.

Otago Medical School Career Pathway after the United Kingdom Years

On their return from the UK, Barbara and Helen stayed to visit with her parents in Auckland. By the time they joined John in Dunedin he had found her a part time job in the pathology department and had arranged for his mother to assist in Helen’s care. The following year she became a senior research officer in the department of surgery, working with the Transplantation Research Group with the orthopaedics professor Norman Nisbet. She thrived on the stimulation of learning new things and thinking about Mendelian genetics once again. (8, 9) In 1962, following the birth of their second daughter Hilary, she returned to work and became head of the research group in 1964, a position she held until her retirement in 1990; she was three-quarters funded by the Medical Research Centre (MRC) and one-quarter by Otago university. In 1972 she was made associate professor and was thought to be the first woman in NZ to achieve this status in a department of surgery; in 1984 she became a professor of surgery at Otago Medical School, the first medically qualified woman to do so. (10)

Barbara had always enjoyed teaching so was happy to do the lectures in pathology in the postgraduate Fellowship of Royal Australasian College of Surgeons (FRACS) program which was started at Otago in 1957 by Prof John Borrie. Over the years the program grew and immunology, her area of expertise, was added to the course. In 1978, Barbara took over the convening of this postgraduate program, which became a charitable trust in 1993, and was involved with it for fifty years. She retired as chair in 2006. Her reputation as an excellent teacher became recognized at an international level and she was invited to teach immunology in Melbourne, Singapore and elsewhere until the 1990s. Barbara recalls her decision to retire from teaching:

I decided to stop teaching in Dunedin in the mid-1990s when one of the candidate assessments said “perfect”. I might perhaps not have stopped teaching if the assessments had not been as good. But it was clear that there was only one way to go – down. So, it was the right time to stop.

Barbara believes she was able to get as far as she did career-wise, because she was able to operate on the fringes of the university system– via the MRC (for research) and the FRACS (for teaching). Her recollection is interesting in this current era of what some consider excessive administrative control:

My own research team was attached to a department (this was a university requirement for administrative purposes), which didn’t really talk our language. …. We were across the road from the hospital-based Surgery Department, and we functioned virtually in isolation.

While the rules for MRC employees were technically those of the host institution (mainly for salary scales) for many things we made up our own rules. I was quite elastic about the working hours for staff with domestic commitments – as long as the work was done. We couldn’t pay overtime for weekend and night sessions for recording timed experiments (we harvested tissues at some unsocial hours) but we made it up with extra holidays. In those days, nobody in the university ever knew who was on holiday and when, so they didn’t notice the operation of our system. It was glide time, well before the idea became fashionable. Today we would have administrators dutifully recording everything, but we were delightfully free of that sort of thing in those days. The departmental secretary was over the road in the hospital, and there were no computers until the early 1980s. I had, however, taken over from Prof John Borrie as convenor of the FRACS course, and we had a secretary, Jenny Hurley, in the Medical School office. We duly found her an office in our set-up. I always sent the lab staff and Jenny to any courses that they wanted to attend. These things were usually free pre-1984. So, the staff upskilled as we went along. I was lucky to have Pam Salmon running the lab, as she had an old-fashioned work ethic, and made sure that nobody abused the system. She and I managed to be quite strict and yet quite flexible at the same time. (Maybe NZ cricket owes me a little for the McCullum brothers – their mother Jan was my animal technician, so of course never had any trouble getting time off to take them to the doctor.)

I had 2 mini-empires on the fringes of the university (the MRC group and the RACS course). We concentrated on teaching the RACS course really well. I was on the examining board in Melbourne, and I knew what the Dunedin course had to deliver. I also knew that we had no real opposition, as I was also teaching this sort of course in Australia and Singapore at the time. I put a lot of work into doing it well, and so we “cornered the market” at a time when financial dealings like this were not quite respectable in academe. Academe distances itself from money in a slightly precious fashion pre-1984. We were not a university organisation, so we could bring in tutors from Australia and pay them decent fees and expenses. Charlie Monroe, the Med School secretary handled the money for us, and JH and I were the rest of the “committee”. It was ostensibly RACS, but actually it was just us. I ran the academic side, and virtually did what I liked with the tuition programme – we aimed to get the best tutors, and everybody knew exactly how I wanted things done. We started to attract large numbers of candidates and made a sizeable profit, which we invested with Forsyth Barr. When postgraduate courses like this, with their associated income, became respectable university activities in the late 1980s and early 1990s, suddenly several university people became interested in it. When it looked inevitable that the university would annexe the course, JH and Charlie Monroe and I made it into a charitable trust (1993). The resultant Dunedin Basic Medical Sciences Course Trust was recently (2011) able to give $300 000 to the neurosurgery chair appeal. It still has about 1.4 million in the kitty.

Barbara published more than 130 research papers and was often invited to give talks overseas. Her major focus was immunology with pioneering research into how to prolong organ graft survival.

Hindsight: Recollection of Her Medical Career

In the interview, her daughters mention the importance of both John and his mother in Barbara’s successful career. John was born in Dunedin in 1925 and was the only child of James, an Irish immigrant and Muriel. His father died in his fifties. The home their parents purchased on their return to Dunedin from the UK was a two-storey house with a flat where his mother lived. She played an important role in caring for the two girls. Barbara recognized she could not have had a career without her mother-in-law as society was not geared for working mothers. In addition, her husband was quite unusual for a man of his era, as he was very supportive of their mother and incredibly proud of her and recognized she was much ‘smarter’ than he was. They were very much a team and had complimentary skill sets.

The following is Barbara’s recollection of medical careers for women from the 1950s to the 1990s:

While I don’t recall Medical School staff ever being unpleasant to us when we were students in the 1940s, active encouragement was rare. The prevailing attitude of the day didn’t really expect very much of medical women after graduation, an attitude that lasted until well into the 1970s. The opinion was widely expressed that the women dropped out (or dropped down) for domestic reasons. In many ways this viewpoint seemed justified – women simply didn’t go for the top jobs. It was only when the numbers of women in the medical classes started to increase that the necessity to arrange jobs a little more imaginatively than had been done previously occurred to the administration. But the health reforms of the early 1990s also helped by modifying the rigid old full time/part time employment rules.

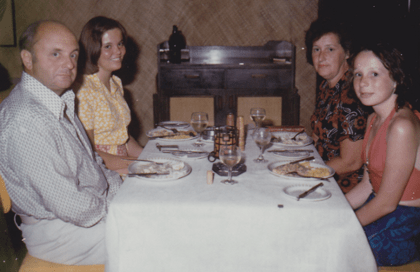

Other Interests

Her daughters remember their mother being a wonderful cook and entertainer and think quite possibly she and John were the ‘early founders’ of the Dunedin food and wine society. She had her signature dishes of the 1970s such as coq au vin and Beef Wellington which she would serve up at three course dinner parties in the middle of the week; they would often entertain overseas and out of town visitors. She particularly enjoyed debating around the table with men she considered misogynists.

She was a member of Zonta, an international service organization of women with the mission of advancing the status of women.

Both she and John were very involved in the Cancer Society and were honoured in 1997 by being made life members. The medical director at the time described her as ‘a powerful advocate for research who gave the committee some profound insights into the strange Machiavellian workings of NZ universities’. (10)

She was quite drawn to crime and whodunits and enjoyed talking about crime scenarios and the perfect crime. During her EGGS student days, she and her friend decided that they could set off the fire alarm and evacuate the school and no one would ever catch them because they were top academic students and would never be found to be guilty. The school launched an investigation to find the culprits, but they never did. Years later Barbara was a witness to an armed robbery and there was a picture of her in the Otago Daily Times being led from the scene. People were ringing John wondering if she was okay to which he replied ‘She’s thrilled, for fifty years she’s wanted to be involved in a crime and was talking about how they could have done it better’.

In her retirement years she entered several writing competitions with her non-fictional works and had three or four of them short-listed for the Royal Society of NZ Manhire Prize for Creative Science Writing. Her favourite was Eomaia’s Children, a 2008 story about rats, the laboratory animal she had worked with in her research. (9)

She was very keen on dogs, in particular Labrador crosses, and her daughters remember they were an important part of the household for many years. Henry and Sam, a rescue dog from Invermay, (the present day AgResearch research station at Mosgiel) (11) were good companions in her retirement years.

Achievements and Honours

Barbara stood out in terms of medical women of her era and seemed to do it with relative ease.

In 1975, she was made a Fellow of the Royal Australasian College of Surgeons, for her contribution to surgical science.

She and Helen were the first mother-daughter duo to both gain their MD from Otago. Thirty-six years after writing her own MD thesis, she and John were on the stage at Dunedin Town Hall when Helen was awarded her MD with distinction. (12) In addition, she was made a Fellow of the Royal Society of Te Apārangi in 1990 (13); thirty-one years later Helen was elected to the National Academy of Medicine. (14)

New Year 1991, she was made a Commander of the Order of the British Empire for her services to medical education and received her honour at Government House, Wellington. Her daughters said how much she disliked wearing hats and complained about wearing one on the day.

Barbara and John’s significant contribution to surgery was commemorated in the Heslop medal approved by the Royal Australasian College of Surgeons in 2004. The medal is awarded to a person who has made a long-term (greater than 5 year’s duration) and outstanding contribution to the Surgical Science and Clinical Examinations Committee and its subcommittees. (15)

In 2017, the Royal Society Te Apārangi, as part of its 150th anniversary celebration published a series of biographies on women who had contributed to knowledge in New Zealand. (13) Barbara was one of the 150 women included.

Retirement

After retiring a few times and being called back into service, Barbara retired for good around 2005 and she and John enjoyed doing some travelling. During the latter years of their eighth decade, John started to develop vascular dementia while Barbara was affected by osteoarthritis which led to her having some orthopaedic surgeries. They moved into Yvette Williams Retirement Home in Dunedin in September 2011 as their health issues became more intrusive on their quality of life. Her daughters remember watching some of the rugby world cup during the move and Barbara saying ‘Only in New Zealand’ when they extended the Bluff oyster season for rugby.

Barbara remained mentally agile to the end of her life and after developing heart failure died on 20 December 2013 at the age of eighty-eight. She was survived by John who died six months later, on 21 June 2014 and her two daughters. Helen is a physician-scientist and is currently a professor at Houston’s Baylor College of Medicine and is the Director of their Center for Cell and Gene Therapy. Hilary is a food product developer. In the past she has worked with large overseas organizations, such as Marks and Spencer, developing food products. She now lives in Melbourne operating her own food consultancy. They both enjoy returning to the family holiday home at Millbrook near Arrowtown.

Following Barbara’s death, the University of Otago established The Barbara Heslop Memorial Scholarship to honour her forty-year career at Otago University in the Departments of Pathology and Surgery, specialising in transplantation research. This scholarship assists students to undertake one year research degrees for BMedSc (Hons) for medical students, BSc (Hons) or BBiomedSc (Hons) – in the disciplines of Pathology or Immunology. (16) An appropriate tribute given Barbara’s outstanding record as a medical researcher. (9)

Summing up Barbara Heslop in 150 words

Immunologist (1925-2013) (13)

A brilliant academic, Barbara Heslop was a pioneer in how to prolong organ graft survival. She had graduated with a degree in medicine from the University of Otago in 1948, a time when not much was expected of female medical graduates. Heslop, however, became an assistant lecturer at the Medical School’s Department of Pathology in 1950. After a stint in London she returned to Otago, initially in the pathology department and then in the department of surgery working on organ transplantation during its early days. Heslop became the head of the research group, publishing more than 130 papers and often giving invited talks overseas.

In 1990 she was made a Fellow of the Royal Society Te Apārangi. That same year Heslop officially retired from the university, but she continued to work through the 1990s: teaching immunology overseas, sitting on the hospital board, and returning to teach undergraduates during a staffing crisis in 1999.

Bibliography

- NZ Private Maternity Homes [29.06.2023]. Available from: https://sites.google.com/site/nzprivatematernityhomes/new-zealand-private-maternity-homes/auckland-region/central-isthmus/grey-lynn

- Births. New Zealand Herald. 1925 10.02.1925. Available from: https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/NZH19250210.2.2.2

- Marriage. Press. 1920 03.12.1920. Available from: https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/CHP19201203.2.2.3

- University Entrance. Evening Star. 1943 22.01.1943. Available from: https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/ESD19430122.2.14

- Heslop B. Postgraduate Training – the Eternal Tug of War for Women and How It Has Got Tougher. In: The Good’s train doctors : stories of women doctors in New Zealand 1920-1993. Dunedin: New Zealand Medical Women’s Association; 1994. p. 50.

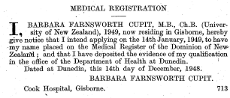

- The New Zealand Gazette [Internet]. Wellington: New Zealand Government Printer; 1948 [cited 26.06.2023]. Available from: http://www.nzlii.org/nz/other/nz_gazette/1948/67/26.pdf

- NZ University Graduates 1870-1961: HA-HE: Shadows of Time; 1962 [updated 06.01.202326.06.2023]. Available from: http://shadowsoftime.co.nz/university11.html

- Cannan D, Heslop H, Heslop H. Obituary of John Herbert Heslop: Royal Australasian College of Surgeons; 2014 [13.06.2023]. Available from: https://www.surgeons.org/about-racs/about-the-college-of-surgeons/in-memoriam/obituaries/john-herbert-heslop

- Cannan D, Baird M. Obituary of Barbara Farnsworth Heslop: Royal Australasian College of Surgeons; 2013 [13.06.2023]. Available from: https://www.surgeons.org/about-racs/about-the-college-of-surgeons/in-memoriam/obituaries/barbara-heslop

- Cannan D. Barbara Farnsworth Heslop: Immunologist, academic. New Zealand Medical Journal. 2014;127(1391).

- Invermay Campus: AgResearch; [29.06.2023]. Available from: https://agresearch.recollect.co.nz/nodes/view/203

- Gibb J. Otago Daily Times. 1990 15.12.1990.

- Martin JE. 150 Women in 150 Words: Barbara Heslop, Immunologist: Royal Society Te Aparangi 2017 [29.06.2023]. Available from: https://www.royalsociety.org.nz/150th-anniversary/150-women-in-150-words/1918-1967/barbara-heslop

- Dr. Helen Heslop elected to the National Academy of Medicine Houston, Tx: Baylor College of Medicine; 2021 [28.06.2023]. Available from: https://www.bcm.edu/news/dr-helen-heslop-elected-to-the-national-academy-of-medicine

- Policy: Barbara and John Heslop Medal 2008 [updated 201915.06.2023]. Available from: https://www.surgeons.org/-/media/Project/RACS/surgeons-org/files/policies/rel-relationships-and-advocacy/pcs-president-council-support/2016-05-24_pol_rel-pcs-032_barbara_and_john_heslop_medal.pdf

- The Barbara Heslop Memorial Scholarship Dunedin: University of Otago; [15.06.2023]. Available from: https://www.otago.ac.nz/study/scholarships/database/otago703405.html