This biography is largely based on the written recollections of Winifred ‘Wyn’ Ethel Morton nee Cox and also information supplied by her daughter Anthea ‘Thea’ Jenkins nee Taverner. All pictures have been supplied by her daughter. Secondary sources are listed in the bibliography. The biography was compiled by Rennae Taylor.

Class of 1924

Contents [hide]

Family History

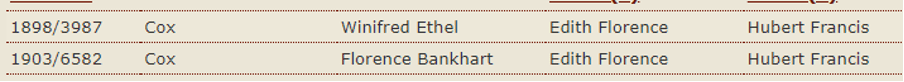

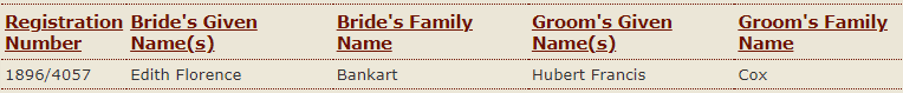

Winifred was born to Hubert Francis and Edith Florence (nee Bankart) Cox on 22 May 1898 at her maternal grandmother’s home at 23 St Stephens Avenue, Parnell in Auckland.

Her sister Florence was born in 1903.

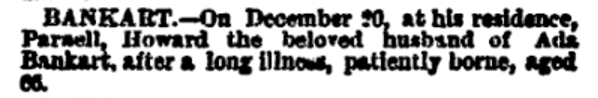

Wyn’s mother Edith arrived in Auckland from the UK in 1887 at the age of seventeen years with her parents Howard and Catherine Adelaide (nee Morgan) Bankart and her three older brothers and two sisters. For some years her father had been the managing director of Brition Ferry Copper Works in South Wales and Coal and Ironstone Works in North Staffordshire. (2) Her father died in 1893 at the age of sixty-six after a long illness, only six years after immigration. (3)

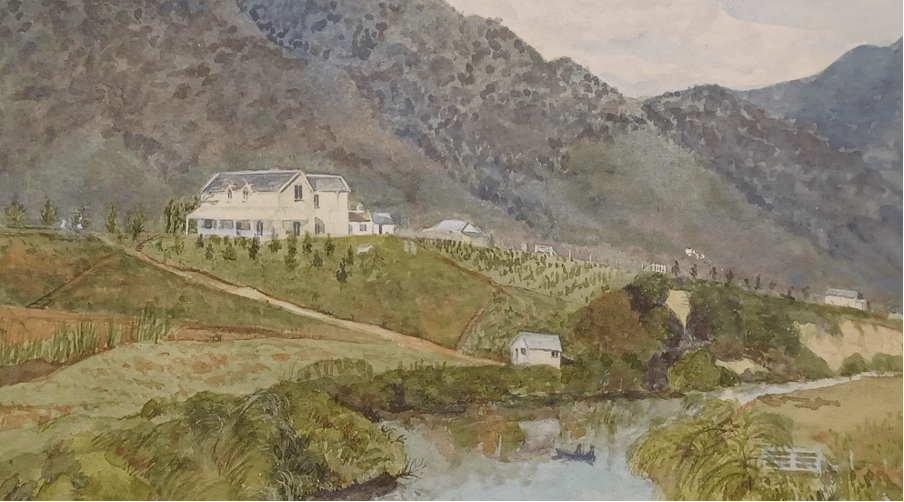

Wyn’s father Hubert immigrated from the UK with his parents, Edward and Sophia (nee Hayter) Cox, at the age of fourteen along with five younger sisters. Edward, a businessman, decided to come to NZ to farm despite having no previous experience. Prior to sailing, he chose from a map a 1000 acre block eight miles from Te Aroha in the Waikato and called it Shaftsbury. Shaftsbury was part of a planned Anglican immigration scheme of Lincolnshire Settlers, and E.Y. Cox led the first group of potential settlers. His wife Sophia had come from a family of silversmiths and was used to domestic help but learned to cope with pioneer life.

Hubert and Edith were married in 1896 (1) and lived on his share of the farm at Shaftsbury.

Childhood

For the first five years of her life, Wyn lived at Shaftsbury with her parents. Her maternal grandfather had died prior to her birth so her memories of her maternal grandmother were of always being dressed in black and wearing a widow’s cap. Wyn’s first five years were quite solitary, but she remembered with affection her spaniel dog ‘Quick’, her pony, and her imaginary sister ‘Lucy’. She recalled going to Te Aroha in 1902 to celebrate the end of the Boer War and being dressed in a new red coat and hat. Sometime after her fourth birthday, her mother started to teach her reading skills on their side verandah.

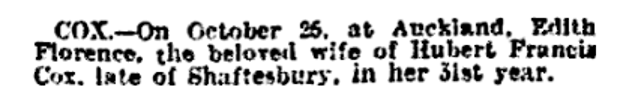

Ten days after the birth of her sister Florence, her mother died from scarlet fever on 25 October 1903. (4)

The next five years were very unsettled for Wyn, her baby sister and father. At the end of 1903, Hubert and young Wyn travelled to England, stayed there for about a year, and then returned to NZ to collect Florence and her nursemaid. There were four trips back and forth which included two unsuccessful farming ventures in England. When the nursemaid left, some stability was provided to the two girls when Hubert’s sister Muriel joined the family. In later years, Wyn felt these very early childhood travels helped her to cope with the changes and challenges she faced throughout her lifetime and made her comfortable with worldwide travel.

Wyn recalled being taught reading, writing and poetry memorization by her father during the ocean voyages. While in England, she briefly attended two private girls’ schools. One insisted on only French being spoken!

Mabel, one of Hubert’s sisters, had married Thomas Russell. When back in NZ, Wyn joined her Russell cousins who were taught by a governess. Wyn and her cousin Jean Russell remained very close throughout their lives. When the family moved nearer to Hamilton, Wyn attended a local school and went to and from on her beloved pony.

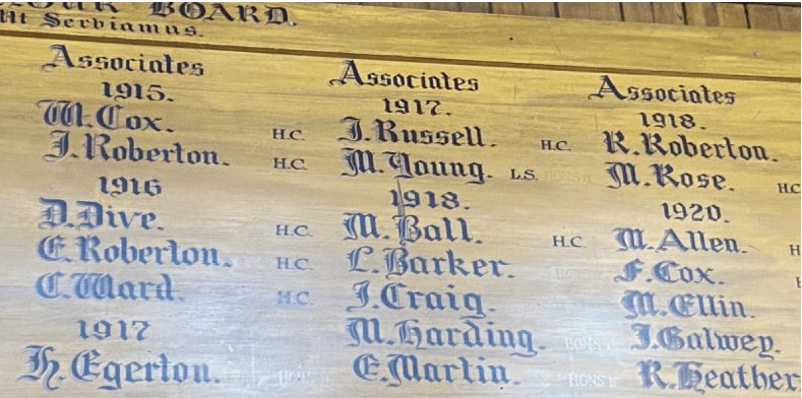

She then became a boarder at Diocesan School for Girls and when the family moved to Auckland, she became a day student. Her name appears on their Honours board for 1915, along with her cousin Jean Russel in 1917, and her sister Florence in 1920.

University of Otago

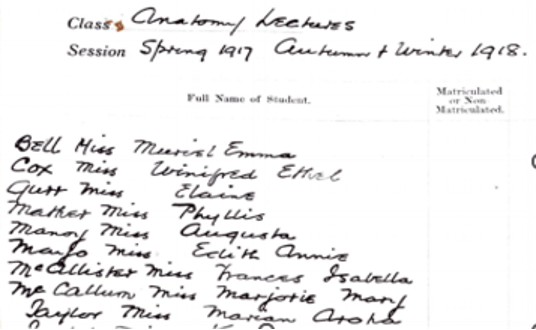

After graduating from Diocesan School for Girls, Wyn took one year off before attending University of Otago in 1917 at the age of eighteen. A close family member said he would provide £500 towards her educational costs provided she studied medicine, so this appears to be her main motivation for going down this career pathway. Like most girls schools of that time, Diocesan School was not strong in sciences so her medical intermediate year was very challenging. She must have studied biology which she managed well, but her inadequacy in maths meant she struggled with physics, inorganic and organic chemistry. With a lot of hard work she managed to pass her medical intermediate subjects and commenced the anatomy classes over the following eighteen months.

In 1917, St Margaret’s was being enlarged so a number of students were boarded out with various people. Wyn, along with three others, lived in a large room with four beds at a Mrs. Wedge’s nearby home. Living in such close quarters meant quarrels occurred but the main argument was ‘who should get up first and brave the cold water in the bathroom’. From 1918 she was at St Margaret’s College.

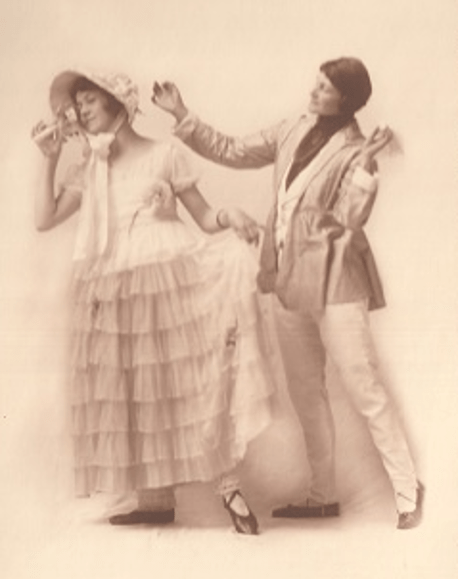

During these years she made lifelong friends including Tui Bakewell (class of 1920), Augusta Klippel (class of 1922), Kathleen Todd (class of 1923) and Edith Mayo (class of 1923) and entered into the campus social scene, which included dancing in amateur theatre productions (on occasion playing the male role as her dancing partner was much shorter), playing field hockey (for the B team) and attending various cabaret and house balls to which she wore an evening frock made by her aunt who made all their clothes due to the family’s limited financial resources. In her memoirs she recalled turning down an invitation to be the only woman taking part in the Capping Concert (a male only domain at that time) because she did not want to upset the other female students but also she did not fancy being a lone woman among all the male performers.

During her time at St Margaret’s, Wyn became quite ill and described this time in her own words:

During the period of study of Anatomy & Physiology, I went home for the May holidays. I went back to Dunedin with a cold and arrived in a snow storm, the result was that I became ill and was confined to bed. Orders were given that nobody was to visit me for fear of catching the infection. One evening I had terrible pain in my chest and hearing two of my friends outside my door I called out to them. Greatly daring, they came in to see what was the matter. One, a charming young Jewish girl, rushed off downstairs to the head of the College, a grim elderly Scotswoman, and dramatically told her “That girl is very ill and if you don’t get a Dr. she will die”. The pronouncement had some effect and a Dr. was called. He was in general practice but also was Professor of Clinical Medicine. He briefly examined me and departed saying I was a “nervous, excitable girl”. He evidently went home and thought about this, came back the next morning and decided I had pleurisy and pneumonia and was too ill to be moved to hospital. Therefore one of the common rooms was made into a bedroom and a night and day nurse engaged. My father and aunt were notified of my plight and set out for Dunedin. There was a coal strike on and the trains were only running in fits and starts so that it took them more than three days to travel from Auckland to Dunedin. They were expecting to attend my funeral but by the time they reached me the “crisis” had passed and I was beginning the long road to recovery. There were no antibiotics then and pneumonia was a killing disease. This wretched interlude meant I had to spend many weeks convalescing and had to leave my studies.

Wyn rejoined the class which had started in 1918 and graduated with her M.B. Ch. B in 1924. She remembers her days of medical training as some of the happiest of her life.

Locums Following Graduation and Early Career at Porirua Mental Hospital

In her memoirs, Wyn recalls the two locums she did after graduation as a young woman not yet able to master automobile driving but needing this skill to go out on locum calls.

Before I was appointed to Porirua I did two locums in general practice, at opposite ends of the country, one at Wyndham in Southland and one in North Auckland. Although in each case I was terribly nervous of the responsibility, no disasters occurred and the experience was good for my morale and general training. In North Auckland, the outgoing Dr. said, “The gears go there, here is the brake” and left for the train. I hadn’t been alone an hour before there was a call for the Dr. There was nothing for it but to take the car and my life in my hands and set out. What risks one takes calmly in one’s youth. During all the two weeks there, I never did learn to reverse and had to think out ways of always approaching forwards. An added hazard was the Northland roads in those days were clay surface and when it rained became like slippery soap.

Wyn recalled how much easier it was for the men to get house surgeon positions compared to women during her era. She applied and was appointed to a junior staff vacancy at Porirua Mental Hospital although she had no intention of specializing in psychiatric medicine. The one advantage was the salary was double the £100 paid to a house surgeon in a general hospital. She describes her time there:

I settled down in a flat attached to one of the villas of the hospital. The work was not arduous as it was before the days of psychiatry as a science. Our work was mostly custodial and keeping patients in good physical condition. I had plenty of free time so I decided to buy a car on time payment. I became the owner of a “Rugby” car and made weekly payments towards its cost. I never had any tuition in car driving merely practiced until I was proficient. The medical staff consisted of the superintendent, a senior officer and two junior officers. My opposite junior position was filled by a succession of young men who came and went as they waited for vacancies in general hospitals.

During my second year at Porirua there came for the other junior position a Dr Frank Morton. He had been at university at the same time as me tho’ a year behind me.

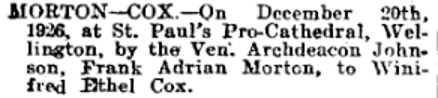

Wyn had never met Frank and on the evening of his arrival found him playing billiards with some patients. She gave him his keys and advised him she would be willing to show him anything he wanted to know. For some time they went their separate ways without much interaction but eventually they started to develop a friendship and discovered they had interests and ideas in common. Frank’s widowed mother and sister and brother lived in the Wellington suburb of Kelburn, and it was not long before he invited Wyn for Sunday evening supper at their home. Frank was appointed a house surgeon at Wellington and would often drive out to Porirua to see her. They married on 29 December 1926. (5)

England Years

At the beginning of 1927, Wyn and Frank started out for England on the S.S. Arawa, a NZ shipping company semi-cargo ship, in order to get further experience and training. Frank was the ship’s surgeon and Wyn was a passenger. He was able to get a position in Stratford in the far east end of London and later at Queen Mary’s Hospital. Wyn found it difficult to find work in England but did various courses in a number of hospitals. While there she was able to visit her paternal grandfather, E. Y. Cox, who had returned to England in 1901 and now lived in Tunbridge Wells. This was a most discouraging time for Wyn.

The months went by and we decided it was no use my staying as I was not in employment and money was scarce so I set sail late in the year to return to NZ. I travelled in the “Port Melbourne” which took ten passengers. I left Frank to follow when he had completed his time at Queen Mary’s Hospital. With hindsight I don’t think this separation was a wise decision but time and chance decide the turns in one’s life story.

Back in New Zealand

On her return at the beginning of 1928, Wyn stayed with her family in Auckland. She helped with preparations for her sister Florence’s April wedding. Frank returned to New Zealand a few months later, again returning as the ship’s surgeon. While in England, he had decided to specialise in anaesthetics and had brought back some modern equipment in order to start the specialty in Auckland. They rented a home in Mount Eden, Auckland. They tried to introduce these new anaesthesia methods to the surgeons for some months but they were possibly ahead of their time and the surgeons were not ready for these new practices.

They realised they would need to turn to general practice and found, in the New Zealand Medical Journal, that a partner was sought by a Dr. D.G. Johnston in Carterton. Frank went down to investigate and found the practice was run by an elderly man and was satisfactory but that the house was very dilapidated. In October 1928, they set out for Carterton. Wyn describes her memories of this time:

The house was large, cold, and inconvenient but optimistically we thought we might alter it or even build when we had made some money…. We knew nobody but soon found the people friendly and we joined the tennis club and the golf club and Frank played in the local cricket team. We settled down to make a home and perhaps even start a family. We did what we could to improve the house, papered some rooms and painted over others but the prospect was daunting. The months went by with hard work, playing tennis, golf and cricket and socialising with a group of contemporary friends and soon we had been in Carterton for eighteen months and it was August 1930. Frank went out to see a patient living north of the borough. Within half-an-hour Dr Johnston rushed into the house and said to me in loud tones “Frank has been killed up at the railway crossing’. I couldn’t believe what I heard, and I remember taking him by the shoulders and shaking him and saying, “It is not true, it is not true”. However, it was only too true. I was terribly shocked both mentally and physically and for many weeks went about in a semi-dazed condition.

Wyn had to make decisions about her future. With her medical training her mode of employment was obvious. She was able to sell the practice and the house and secured a position as house surgeon at Cook Hospital, Gisborne. From her memoirs it does not appear that she did any medical work in the Carterton practice.

House Surgeon Years

On 3 February 1931 she set out for Gisborne by train. About halfway to Napier, the guard came through the train and said they could go no further as there had been a ‘devastating earthquake’ in the Hawke’s Bay and Napier was destroyed. Wyn returned to Palmerston North, took a train to Auckland and then a service car to Gisborne.

She found on arrival that Cook Hospital was a ‘Closed Hospital’ meaning there were no visiting physicians and that the superintendent and the house surgeon did everything for the 150 beds. Wyn recalls this time:

This was excellent training and I soon learnt to be proficient at many activities denied to house surgeons in bigger hospitals, for instance I could dissect out tonsils in seven minutes. While my medical ability improved my private grief continued and I often felt despair and had no interest in anything beyond my work. I had some old friends in Gisborne and made a few new ones, but I had very little free time and was always on call as I was the only house surgeon. During the time I was in Gisborne we had frequent earthquakes following on the heavy one of 3 February 1931 and always had to evacuate the patients in case of real disaster. During my second year in Cook Hospital a junior house surgeon was appointed, one Garth Stoneham whose family lived in Gisborne. We shared a two-bedroom flat in the hospital building. One night there was a bad earthquake and we each had wards in which we had to supervise the evacuation. I made my way along a swaying corridor and there was no sign of Garth. Later when all had calmed, I said to him in annoyed tones “Where were you during the quake”? He said, “I was searching for my trousers”.…. Of course, during these quakes all power is turned off in case of fire so there is complete darkness except for torches.

After two years in Gisborne, Wyn applied and was appointed to a house surgeon position at the larger Palmerston North Hospital in September 1932. There were supposed to be four house surgeon positions filled but the fourth person never turned up, so the workload was heavy. There were several honorary visiting physicians and surgeons, and each had a house surgeon allocated to him. Wyn describes her allocation:

I was allocated to Mr David Wylie who was a nationally known surgeon at that time tho his reputation was quite unknown to me. On the first day that I was assisting at his operations he accused me of doing something wrong such as not tying off an artery or misplacing a swab. I said “I didn’t do that Mr Wylie” and went on with my work. He took two steps back from the table and stared at me, I took no notice and went on with what I was doing. The theatre sister on my left nudged me delightedly. I was quite unconscious of the drama as I didn’t know that Mr Wylie was a local god. Finally, he got tired as he obviously was making no impression and came back to the table and went on operating. The sister told me afterwards he had reduced previous house surgeons to tears. After this display of bullying when he saw he wasn’t going to intimidate me, we became friends and I worked with him all the time I was in Palmerston North and he taught me a lot. I soon became senior house surgeon and had a great deal of responsibility, and the workload was heavy…. After two years at Palmerston North, I felt it was time I made another move but what to do I felt uncertain.… However, just at this time two friends of mine, the sisters Kath and Moyra Todd, were going to England and suggested I go with them.

Travelling, Overseas Work and Courtship by Letters

In late 1934, Wyn left with the Todd sisters, Kathleen Todd, who had graduated from medicine in the year ahead of her, and her sister Moyra Todd, a singer. Kath studied and lived in England for several years before returning to NZ in 1946 to run her own private practice in Lower Hutt. (6)

The three of them had a four-month voyage to the UK with stops in South-East Asia, a ski holiday in Switzerland and a tour and camping holiday in England. By September 1935, money was getting low, so Wyn applied and was successful in being appointed to a position at the hospital in the town of Stamford, in Lincolnshire. She recalls the 17th and 18th century stone buildings which contrasted with the modern Woolworths building in the centre of the town.

American friends had suggested Wyn should come to the States, but she advised that without a job this would not be possible as she had no cash. They kindly found a position for her as an obstetric resident at the Women’s Hospital in Philadelphia with a start date of 1 May 1936. The hospital, established in 1861, provided clinical experience for Women’s Medical College of Pennsylvania who trained women in medicine. (7) She left Stamford in mid-April and sailed to the USA on 22 April 1936 and by mid-May she felt she had acclimatised to her new obstetric role in this ”foreign” land which did not understand her accent. Her friends, particularly her Otago medical school friend, Edith Mayo, were very good to her and made sure she was taken care of.

Following the death of Frank, Wyn had relied on the assistance of their Carterton lawyer, Douglas Lacy Taverner, when selling the medical practice and house. Sometime in August 1936, Wyn unexpectedly received a letter from him suggesting she come back and marry him. Wyn’s memoirs recount her response:

This surprised me to say the least and I thought he must have been feeling lonely one day and sent the letter on impulse – in later years I came to know that he did nothing on unpremeditated impulse. This suggestion started a long discussion which was to last for two years.

Wyn stayed in Philadelphia with her friend Edith until 18 November 1936 when she set sail for England on the recently launched Queen Mary. The Todd sisters welcomed her into their rented Hampstead home where Wyn was able to board.

It was around this time that the storm broke over King Edward VIII and the American divorcee Wallis Simpson. The English had been quite unaware of it whereas Wyn had followed the rumours through the USA papers. Wyn recalls this historical moment:

On the evening of December 11th Moyra Todd and I went to the theatre and on the way home joined a crowd outside 145 Piccadilly, the home of the Duke and Duchess of York, Edward’s next brother on whom the succession would fall. That evening there had been a family farewell dinner and Edward made his abdication speech over the radio. After we had been standing in the crowd awhile a car drew up and into the courtyard and out stepped the Duke of York. He turned towards the crowd for a brief minute and the crowd chanted “We want the King and the Queen”. The next day Albert Frederick Arthur George was proclaimed George VI. Edward had sailed for France the night before.

In between a couple of bouts of influenza, Wyn did a few locums at various London City Council hospitals where she was often challenged, particularly one where she was the senior obstetric doctor and found that the students and nurses did all the normal cases, and she was to be the ‘oracle’ on the complications. She was pleased to hear from the sister at the end of the locum that she thought obstetrics was her speciality. In addition, she and the Todd sisters had a spring holiday in Austria that year and managed to get allocated seats in Hyde Park for the coronation on 12 May 1937. By the summer she had managed to buy a car and she and her NZ friend Beatrix ‘Tui’ Bakewell, did a road trip to Devon. In addition, Wyn describes her pondering over her future:

Time was running out for me to make up my mind about returning to NZ and to make up my mind as to what I was going to do with the rest of my life and once again fate took a hand. Among the various people who came to England that summer was an aunt by marriage (Lady Alice Bankart), the widow of my favourite uncle. She suggested a European tour if I would accompany her and more or less take charge.…. This offer of an all expense paid visit to various European cities I had never seen was too good to miss, so I gratefully accepted. On August 21st we left on the Orient Express for Vienna and stayed at the Hotel Bristol. I had never travelled in such luxury. Aunt was well provided with money and used to comfort.…. We returned to London at the end of Sept. The year was into its last quarter. All this year (1937) Douglas Taverner had been writing to me, still quite sure he wanted me to return to NZ and become his wife. I had many reservations and could not make up my mind when such a great distance separated us so finally decided to go back to NZ and consider the project.

Wyn booked her passage on the P&O liner ‘Strathmore’ in December 1937 and arrived in Wellington 1 January 1938 where her brother-in-law met her but no Douglas Taverner. The romance was off to a bad start as Wyn was quite annoyed with him. His brother in England had asked her to bring a shotgun out to him. On arrival, she had the customs and police questioning her why she was bringing a firearm into the country. She finally got to her mother-in-law’s flat in Kelburn where she was planning to stay in the short term. Douglas arrived a few hours later and they started becoming acquainted with each other after several years with no in-person contact.

Marriage, Motherhood and World War II Years

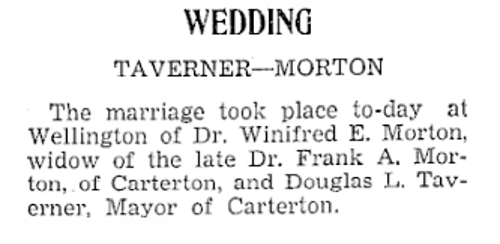

After several weeks of courting, Wyn finally made up her mind to marry again and learn to be a housewife and live in a small country town. The wedding was planned for Easter as Douglas would have ten days’ vacation at this time. They were married on 4 April 1938 (8) and spent their honeymoon at Taupo fishing. By this time Wyn was nearly forty years of age.

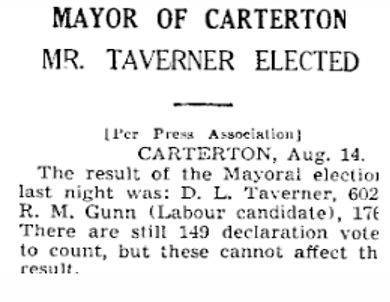

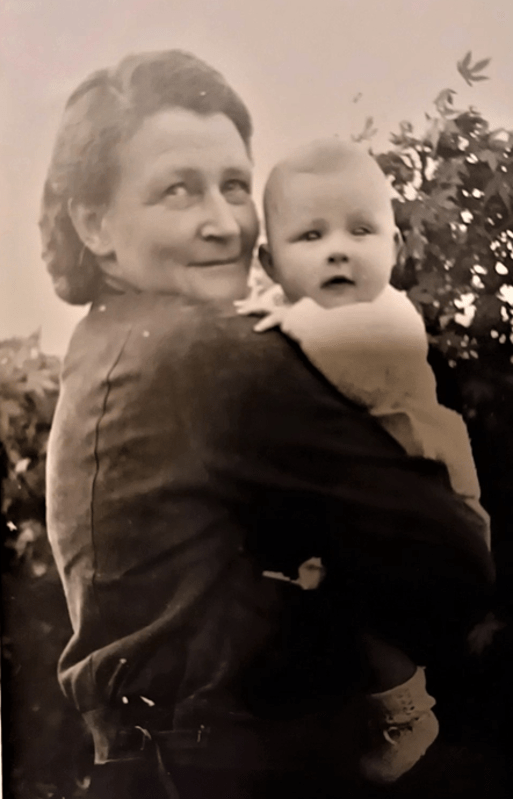

Wyn learned that fishing and shooting were one of Douglas’s abiding passions. They bought a house in Carterton and during the first year Wyn learned to cook and do housework and became pregnant. Their only child, Anthea (shortened to Thea) was born on 23 June 1939, three months before World War II broke out. Douglas had been elected to the mayor’s position in 1936, (9) so Wyn had to occasionally appear as mayoress until he retired from this public duty in 1947.

Wyn describes her World War II years:

After some months there was only one Dr left in each of the South Wairarapa towns as they went off to join the war services. Because of this a deputation came to me saying it was my war time duty to practice my profession. At that time medical practice in the country towns was more comprehensive than today, general surgery was done in the Public Hospital in Greytown, and in private hospitals in Martinborough, Featherston, and Carterton. Added to this were maternity homes in each town. Today all surgery and maternity is undertaken at the main hospital in Masterton, the chief town of the Wairarapa. My role was to be assistant to my Carterton colleague, to give anaesthetics throughout the district and to do locums in each of the towns to allow the resident Dr to have time off. I managed to engage a Karitane nurse to look after the child, but I still had housework and cooking to do as well as my professional duties. Every so often the Carterton Dr would go off for weeks at a time and leave me with the whole district. It was a heavy workload and not made easier by the fact that Douglas was Mayor of Carterton at the time so occasionally I had to make an appearance as a mayoress.

One day went thus: the current Governor-General and his Lady decided to visit Carterton on the day of the A&P show. I was actually doing a locum at Featherston at the time so thought I would elude the whole thing, but Douglas would have none of that, so I did the morning surgery hours and then drove home where I changed into something suitable to meet the vice regal pair and dressed the four-year-old daughter in an organdy frock so that she might present the bouquet at the opening ceremony followed by lunch with local dignitaries…. Following the ceremony and lunch at the hotel with local dignitaries, the afternoon was spent at the show and we finally saw them drive away back to Wellington. I then went home and prepared the evening meal after which I drove back to Featherston and during the evening delivered triplets!! I did not have to appear as mayoress very often thank goodness as I had more than enough work without social obligations.

The war years passed and the necessity for me to practise was less insistent which was just as well for the stress of those years caused me to have a serious illness – a perforated gastric ulcer which meant emergency surgery. I recovered very well and took up daily life again.

After the war Wyn became a stay-at-home wife, mother, and homemaker once again. Her daughter, Anthea, attended Carterton for her primary schooling, and then became a boarder at Woodford House in the Hawkes Bay for her secondary education. She became very keen on riding so through her childhood years they had ponies and then a hack (a type of horse used for riding). Wyn spent a lot of time at the A&P shows and Saturday horse sports with her daughter which she enjoyed.

In 1948, when Anthea would have been nine years of age, they purchased a section at Waikanae, and built a cottage. Over the next thirty years they spent the summers there, enjoying the beach and swimming. Anthea recalls the cottage with warmth:

In 1948 there were still restrictions on building a second residence if you already owned one. My parents discovered the original pioneer Greytown Post Office hidden behind the newer one. Built with kauri boards an inch thick it was still in usable condition. They purchased it, had it cut into sections, loaded onto three lorries, and driven over two mountain ranges to Waikanae. Erected on their section, painted throughout and with a veranda added, it become the summer place of my childhood and teens. In the summer of 1974-5, my own children had a wonderful time there. I really hope it still stands. It was there when I saw it some years ago, sitting quietly among the large expensive houses – Waikanae having become an affluent suburb of Wellington.

Retirement Years

Anthea went to Otago University where she studied Dietetics in the School of Home Science. She did a one-year internship in dietetics at Auckland Hospital in 1960 then, like her mother, decided to travel. She had short-term positions in London hospitals from 1961 to 1963, before travelling to Canada where she worked in a Peterborough, Ontario hospital.

In July 1964, at the age of sixty-six, Wyn found someone to keep house for Douglas, and decided to go and see her daughter. She embarked on her first overseas long flight with some apprehensiveness (Auckland-Honolulu-Vancouver). Anthea met her on arrival, and they toured through the Rockies to Calgary then flew to Toronto, saw Niagara Falls, then spent a week in Peterborough where she met Anthea’s friends before continuing her travels on her own. She enjoyed reconnecting with her old friends made during her time working in Philadelphia years before.

Towards the end of 1964, Wyn received a phone call from Anthea, to say she was marrying a young Canadian named Ernest Jenkins, an architectural designer who she had met in Peterborough. They were married in November 1964 and visited NZ in February 1965. Wyn and Douglas were sad to lose their only child to the other side of the world but realised “that people make their own lives, and one can’t interfere too much”. Anthea continues to live in the family home in this small city of Peterborough. Anthea and Ernest had a son in 1966 and twin girls in 1968. None of Wyn’s grandchildren have followed a medical career. In addition, Anthea left the health sector and spent the last seventeen years of her career in Human Resources.

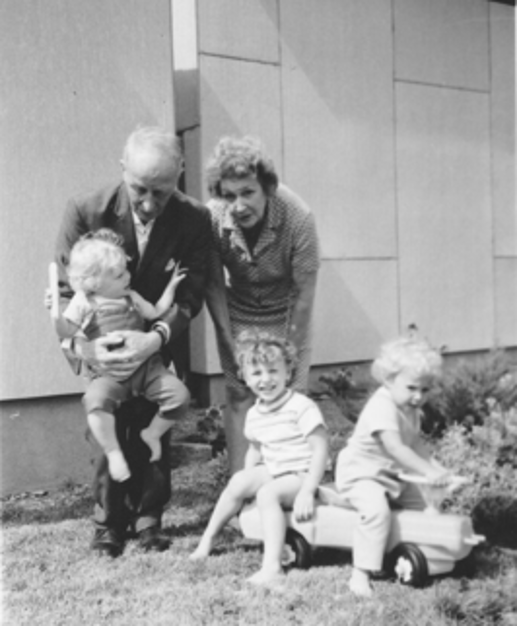

By 1970, they had three grandchildren they had never met and Douglas, now seventy, had mostly retired from his law practice although he kept on a few of his old clients into his eighties. He had never travelled outside of NZ. Wyn thought it was quite time he saw a bit of the world, so they planned a tour beginning in Canada in order to see the family there.

They did much the same trip that Wyn had done in 1964 but stayed three weeks in Peterborough, Ontario and got to know their grandchildren (Mark and the twins, Catherine and Anne, now three and half and two years of age respectively). They then went on to London and toured England, Scotland, Ireland, and some of Europe. Douglas was able to spend time with his brother and sister who had lived in England for many years while Wyn enjoyed the theatre, choosing plays that would not interest Douglas. They had a wonderful cruise home via the Panama Canal. Two years later, in 1972, they did a cruise to Japan which unfortunately had a shipboard engine fire while docked in Hong Kong. Douglas decided the homeward journey could not include ten extra days in Hong Kong as it would interfere with the start of the “duck shooting” season! They also enjoyed a visit from their Canadian family during the Christmas holidays of 1974-1975 and spent family time at their cottage in Waikanae.

In May 1978, Wyn celebrated her 80th birthday with her NZ family and friends. The following year her health broke down which resulted in surgery. The last entry in her memoir’s states “since then I have never been well and am quite prepared to end this long saga”.

Wyn died on 27 August 1987 in her 90th year. She was survived by her husband who moved into a retirement home in 1990 and died in December 1992 at the age of 93 years.

Winifred Ethel Morton was Carterton’s first and Wairarapa’s second woman medical practitioner. Her friend and colleague Dr Dorothy Potter wrote in the New Zealand Medical Journal obituary: (10)

Few medical women of her era had such a diverse practising life. To the town which Wyn adopted, she gave liberally of her expertise and wished she could have done so medically for longer. As Dr Morton, she is remembered by patients with much gratitude and by those who knew her as Mrs Taverner with tremendous admiration.

Bibliography

- Births, Deaths & Marriages Online Wellington: New Zealand Government – Internal Affairs; [08.08.2022]. Available from: https://www.bdmhistoricalrecords.dia.govt.nz/

- The Rabbit Pest. Auckland Star. 1887 18.05.1887:4. Available from: https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/AS18870518.2.25

- Deaths. New Zealand Herald. 1893 19.12.1893. Available from: https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/NZH18931229.2.63.29.3

- Deaths. New Zealand Herald 1903 11.11.1903. Available from: https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/NZH19031111.2.91.29.3

- Marriages. New Zealand Times. 1926 31.12.1926. Available from: https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/NZTIM19261231.2.4

- Labrum B. Story: Todd, Kathleen Mary Gertrude Wellington: Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand; 2000 [21.08.2023]. Available from: https://teara.govt.nz/en/biographies/5t15/todd-kathleen-mary-gertrude

- Woman’s Hospital of Philadelphia: Wikipedia The Free Encyclopedia; [updated 29.06.202321.08.2023]. Available from: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Woman%27s_Hospital_of_Philadelphia

- Wedding. Wairarapa Times-Age. 1938 04.04.1938. Available from: https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/WAITA19380404.2.80

- Mayor of Carterton. Wanganui Chronicle. 1936 15.08.1936. Available from: https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/WC19360815.2.77

- Winifred Ethel Morton. New Zealand Medical Journal. 1988;101(840).