This biography has drawn heavily on the book ‘The Unconventional Career of Muriel Bell’ written by Diana Brown, MA in History from the University of Otago. Photos are courtesy of the Hocken Collections, Otago University Library. Other sources are listed in the bibliography.

Class of 1922

Contents [hide]

Family History

Muriel Emma Bell was born on 4 January 1898 to Thomas and Eliza (nee Sheat) Bell on their farm at Four Rivers Plain, just out of Murchison in the Tasman area. (2)

Muriel’s maternal grandfather, John Sheat, was from Somersetshire, England and, as a twenty-two year old, immigrated to Nelson in 1842. He married Eliza Avery in 1848, and they had seven children. Their youngest was Muriel’s mother, Eliza Sheat. (2)

Her Scottish paternal great-grandfather arrived in New Zealand with his family in the 1840s as well, and he eventually settled in the Motupiko Valley, Tasman, where he started to raise sheep. His eldest son, James, met an immigrant ship in Dunedin and was introduced to Mary Ann Caradus, a young “God-fearing girl”, and very shortly married her. They had seven sons and one daughter. Two of their sons, Thomas (Muriel’s father) and James, purchased a farm in 1885 at Four Rivers in the Murchison area. Gold mining on a small scale and bush farming were the main settler occupations in the Murchison area, with dairy farming starting later. The two brothers also operated a sawmill on their land. The area was often damp and clad in fog, and communication with the outside world was poor due to its remoteness. (2)

In 1886, Thomas and Eliza were married in Richmond and settled on the farm at Four Rivers. (2) They had eight children beginning with Frank (1888), Mary who died in infancy (1889), Eliza (Elsie) Grace (1890), Leslie (1892), Arthur (1894), Muriel (1898), Christina (1902), and Jessie (1905). (3)

Childhood

Muriel was born into this pioneering farm life in the Murchison area where there were few roads and rivers had to be forded on horseback. The Bells were a prominent family in the area. Her father was involved in local politics and was a member of the licensing bench and the school committee, and presided at local sports events and concerts. Her parents were active in the Methodist church community and helped with the founding of the local interdenominational Sunday school for settler’s children. Her father was a lay minister, and her mother was the church organist and was well known for her charitable works and hospitality. (2)

Medical services in Nelson were a day-long journey from Murchison, so local accidents were often fatal. Muriel’s father became self-taught in medical and rudimentary surgical skills. He had his own set of surgical and dental tools and was known to set limbs before transfer to Nelson, extract aching teeth, and assist in performing emergency surgeries. In 1906, Murchison was successful in appointing their first doctor. (2)

Muriel’s later childhood was exposed to several family losses. In 1905, her eldest brother Frank had two operations due to acute appendicitis and died. In 1906, her younger sister Jessie was born. She was described as a frail child with an alimentary canal abnormality, and Muriel often took care of her. She died before her first birthday. Her brother Wallace said Muriel’s life-long loathing of funerals probably stemmed from this time, as Jessie’s funeral included the Victorian ritual of mourning: four little girls were the pallbearers, wearing white dresses, black hair ribbons and sashes. In the same year as her sister’s death, her mother burnt herself badly doing the laundry in a copper tub. James took his wife on a convalescent trip to Christchurch and left the children in the care of a local resident. The trip in those days was via Wellington, and on their homeward journey, they were involved in a tram accident that caused the outright death of her mother. The inquest indicated that the cause of the accident was that the reversing lever had been placed in the wrong position. Their future stepmother, Jessie McNee, was the Murchison postmistress at the time and delivered the sad news to the farm via horseback. (2)

Following the accident, her father decided to leave the district, possibly due to his own ill health. In 1907, he purchased a 100-acre farm in the Richmond area with a large hilltop home, orchards and gardens. He married Jessie McNee, and they had two children, Jean (1910) and May (1916). (3) He again became involved in local public affairs, lay preaching and became the mayor of Richmond on 2 May 1917, eleven days prior to his sudden death. (2)

Schooling

Muriel attended the local school in Murchison, where her brother described her initially as a “reluctant student”. She learned beautiful handwriting from her headmaster and was noted to have a very pleasing singing voice. In 1907, she began travelling by train from Richmond to Nelson with her two older brothers, where she attended Nelson Girls’ Central School. She showed an aptitude for learning and, in her last year, won a junior national scholarship and enrolled in Nelson Girls’ College as a day student in 1911. In 1915, she became the head girl on the basis of her scholastic achievements. In later years, she recalled her enjoyment of plays and concerts, botany expeditions, listening to stories during sewing lessons, and singing lessons. (2)

Higher education for girls seemed out of reach, and a university education was not on her horizon. However, she was awarded a university scholarship, and because she excelled in languages, she began an arts course at Victoria University, Wellington, in 1916. (2)

During this era, opportunities were opening up for women in the sciences. The University of Otago had started the School of Home Science in 1911. In addition to the influence of her father’s medical attention in the pioneer settlement of Murchison, her older brother Leslie was influential in directing her on the medical trajectory. No doubt, he would have been exposed to some of the early medical women such as Doris Gordon and Francesca Dowling. In her book, D. Brown describes his influence on Muriel: (2)

Muriel’s brother Leslie was a medical student at Otago University when World War I broke out in August 1914. He interrupted his studies to join the Expeditionary Forces, which landed in Gallipoli in 1915. He was a sergeant (and later a lieutenant) in the medical corps and served in the NZ Field Ambulance Corps in Gallipoli. The following year, the army corps removed him from active service because of severe diarrhoea: he was admitted to a base hospital in Alexandria and then to St David’s Hospital in Malta with jaundice. Later, in Cairo, the corps discharged him as unfit for duty and sent him back to New Zealand to finish his medical degree. On hearing that Muriel had started university, Leslie wrote suggesting that she should do a medical course. Muriel wrote ‘a very careful letter to her father asking what he thought of the idea. He was delighted and telegraphed his wholehearted approval.’ In a later interview, she speculated that at the ‘back of his ready consent was his own thwarted desire to be a doctor’.

Medical School

Muriel began her medical training at the University of Otago in 1917 and stayed at St Margaret’s College. Unfortunately, her father died in May 1917, and her stepmother, possibly due to financial necessity, sold the Richmond property and moved back to Murchison. Thereafter, money was in short supply for the Bell children’s studies. However, Muriel did have family support in Dunedin; her brother Leslie was finishing his final year of medical school in 1917, and in 1921 her younger sister Chris enrolled at Otago and studied mathematics. She was also close to her cousin, Raynor Bell, who was appointed chair of clinical dentistry at Otago in 1920. (2)

Muriel participated in various university activities, including the Christian Union where pacifist discussions were common, a Bible Study Group, Otago University Students Association (she was the first “Lady Vice-President), the Social Club, the Capping Ball Committee, and the Women’s Faculty Club. The conservative stance of her parents declined once she left home, and she was drawn to Christian socialism. Her friends in later life remembered her as having little tolerance for religion while maintaining a lifelong commitment to pacifism. (2)

Muriel’s later recollection of her student days was that women medical students were not altogether welcomed at the time. Engraved on the desk she sat in was the slogan “Women’s place is in the home.” She was in the last class to complete a five-year rather than six-year medical training. The first year focused on the elementary sciences of chemistry, biology and physics; the second year included the dissection room, laboratories, and wards for anatomy and physiology instruction; the third year covered laboratory study of preclinical subjects such as bacteriology pathology, systemic medicine, clinical medicine and surgery; and the fourth year provided instruction in various specialties such as ophthalmology, obstetrics, radiology and anaesthesia before the final year of clinical instruction. (2)

Her friend and classmate Frances McAllister recalled that Muriel showed an early aptitude for scientific laboratory work – “she was extremely careful and particular and arrived at results by reasoning and scientific methodology”. (2)

Of all the professors at the medical school, John Malcolm, the professor of physiology with a special interest in metabolism and nutrition, had the most profound influence on Muriel’s life. He was the first professor to use animals for his practical physiological teaching, such as wild rabbits for blood pressure measurements and frogs for muscle studies. Muriel went on to later replicate this practice in her own teaching and research. (2)

She spent her final year at medical school as a public health bursar. The scheme accepted eight bursars annually to live in at Dunedin Hospital (the only NZ hospital at the time with any accommodation for women), where they gained valuable experience by assisting the house surgeons; 1921 was the final year of the scheme. Her classmate Elaine Gurr, the only other female bursar that year, remembered the experience as ‘arduous days’ and commented that ‘house surgeons made them work very hard’. Bursars, like other students, had to attend lectures and complete practical work in addition to their hospital duties. There was no laboratory assistance for diagnostic testing: house surgeons and bursars did their own blood counts and urine tests on patients. They were on duty every night and at weekends for calls to the wards, operating theatre and casualty department and were responsible for their supervisors’ patients. They also had to respond to emergency calls, which were often in the poorer areas of Dunedin. (2)

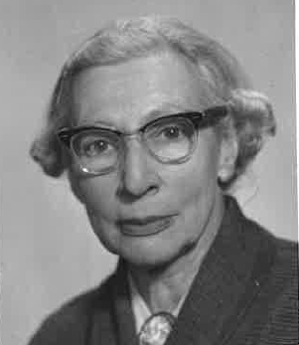

The class of 1922 had twelve women graduates. Muriel made some long lasting medical friendships at St Margaret’s including Augusta Manoy (later Klippel), Eily Elaine Gurr, and Frances McAllister (later Preston).

Early Post Graduate Years

Upon graduation, Muriel was offered a position by the Professor of Physiology, John Malcolm and became his assistant, which involved teaching, research and experimental work. The use of experimental animals had only begun at Otago Medical School in the 1920s, and their feeding became one of her responsibilities. In this position, she was exposed to the latest journals which reported on the new discoveries in the field of nutrition, and this inspired her own interest in this area.

Professor Malcolm encouraged Muriel to do her Doctor of Medicine (MD degree), a research qualification that few doctors at that time were interested in doing. Her research was built on the earlier work of Sir Charles Hercus, Professor of Public Health and Dr Eleanor Baker-McLaglan. Her thesis, which received a first-class grade, was entitled, ‘Clinical studies in basal metabolism in goitrous cases in New Zealand’ and contributed to the introduction of iodised salt in NZ. (4) It is interesting to note that she fell short by 3 per cent on the written examination, and initially, her MD was not going to be granted.

Her external examiner, Dr Blackburn of Sydney, had given this summary of her thesis: (2)

This is excellent and represents a large amount of ingenious work. It shows careful thought and sound judgment in regard to deduction. Will get first class MD.

Malcolm went to her defence and wrote a letter to the faculty and called on the University Senate to rectify the ‘miscarriage of justice’ of not passing her. He wrote:

The function of an internal examiner is to modify the opinion formed by the external examiner who judges the candidate merely on one examination. This he should be able to do from his personal knowledge of the candidate’s abilities and clean record. Professor Carmalt-Jones made full use of Miss Bell’s ability to determine metabolic rates both in Hospital and in his private practice and yet he is unable to allow her excellent thesis to counterbalance a deficiency of 3% in her paper while he raises the clinical marks of another candidate (Mackay) so as to allow him a pass.

The matter was resolved, and Muriel graduated in 1926, the only living woman in New Zealand at this time to hold this degree. (5) She continued as Malcolm’s senior assistant in physiology until the end of 1927. Muriel knew that postgraduate study overseas was necessary to further her academic career in physiology, and she left with the encouragement of Malcolm. (2)

New Zealand Medical Women’s Association (NZMWA)

The NZMWA was formed in 1921, and by 1923 Muriel had become involved in the Dunedin branch and had presented a paper on Basal Metabolism. In 1927, she presented a paper on recent findings in physiology – in particular, ‘The role of calcium in diminishing the permeability of capillaries, and the regulation of the calcium content of the blood’. In her 1928 post-graduate trip, she represented NZMWA at the Medical Women’s International Association conference in Bologna, Italy and in 1931, she represented the NZMWA at the Fifth Imperial Social Hygiene Congress on ‘The Venereal Diseases Problems Throughout the Empire’ in Vienna, Austria. She served as vice president of the Dunedin branch from 1938-39. (5)

First Marriage

Through her involvement in the peace movement, Muriel met her first husband, James (Jim) Saunders, who was eighteen years her senior. He was born on a station in the Maniototo and spent his early years working in the West Coast coal mines, which were a hotbed of radical socialism in nineteenth-century New Zealand. During World War I, he was a conscientious objector on religious and socialist grounds (6) and was sentenced to prison camp labour planting trees. In later years, he took Muriel to the Kaingaroa state forest and showed her thirty-foot pine and fir trees and said: ‘There, isn’t that better than graves in Flanders?’ (2)

On 10 January 1928, Jim and Muriel married at the registrar’s office in Wellington. She was thirty years old. Until his death of a heart attack on 31 May 1940, her career took priority, and he looked after their domestic life. (2)

Muriel used her own name professionally throughout her lifetime. However, officially and in her private life, she became Mrs. James Saunders. (2)

Overseas Post-Graduate Years

In 1928, Muriel and Jim travelled to England and Europe. At that time, it was common for medical graduates to undertake three months of clinical training overseas toward a professional qualification known as a ‘testimonial’. Muriel went to Vienna to gain further knowledge in the area of rachitic convulsions (seizures associated with rickets, due to vitamin D deficiency). She then gained laboratory experience at the Royal Free Hospital for Women in London before returning to New Zealand in 1929, where she took up the position of pathologist at the 250-bed hospital in Napier and put in twelve-hour workdays. (5)

Muriel was successful in gaining the William Gibson Research Scholarship in July 1929. This scholarship was awarded every two to three years to qualified medical women of the British Empire and entitled the holder to do research work at either the Lister Institute or University College, London. (5) For the second time, she and Jim left for England on 7 December 1929. (2)

Prior to going, Muriel had been asked to carry out a six-week investigation into an outbreak of the ‘bush-sickness’ sheep ailment on a farm near Te Kuiti, although it had been previously observed in other farms in both the South and North Island. It caused the fleece to fall off and left ewes weak and unable to rear their lambs. In particular, she was asked to investigate whether it was due to calcium deficiency. She found that sheep recovered when given a drench of iron and ammonium citrate. Through this seminal work, she found that a cobalt deficiency in the soil caused by previous volcanic activity was the problem, and the remedy was cobalt supplementation. (7) It is possible that this very early work which she did for the Department of Scientific and Industrial Research (DSIR) led to her lifelong interest in the study of trace elements and their effect on human health. (2)

In her book, Brown identifies that the training in biochemistry that Muriel received in London provided the ‘cornerstone’ of her future career in nutrition. From 1930 to 1932, she worked in the Department of Biochemistry at University College, London, with Professor Jack Drummond, who was known for his outstanding work in nutrition. He was concerned with finding ways to provide better nutrition to low-income families and then pass this knowledge on to the politicians. As a result of Muriel’s research work around this time, six papers were published:

- 1931: The blood sugar level in vitamin B(1) deficiency. (8)

- 1933: Studies of the alleged toxic action of cod liver oil and concentrates of vitamin A. (9)

- 1933: Albuminuria in the normal male rat. (10)

- 1933: High protein diets and acid-base mechanism. (11)

- 1933: Cystine and nephrotoxicity (12)

- 1935: Observations on the absorption of carotene and vitamin A. (13)

While in London, she and Jim lived in private flats. Jim looked after the domestic affairs and pursued his political interests as a pacifist and possibly a communist. (2)

At the end of her research scholarship, she found employment as an assistant pathologist at the Elizabeth Garrett Anderson Hospital in London, a hospital run entirely by women. (2)

In 1934 she worked at the Royal Infirmary Sutherland again as assistant pathologist. Here in these coal-mining areas in the north of England, she was exposed to the economic depression with high unemployment rates (between 20 and 50 per cent). (2)

She did not initially intend to return to New Zealand after her studies as there were limited opportunities for her career as a female scientist. Her old friend Peter Fraser, now the minister of health and education in the 1935 Labour government, may have influenced her decision to return. (2)

Mid-Career Years

In 1935, Muriel and Jim returned to Dunedin where she resumed the position she had held five years previously as lecturer of physiology and experimental pharmacology at Otago Medical School, a position she was now over-qualified for. (2) She was known as Malcolm’s ‘right hand man’. On leaving the department in 1940, a student wrote: (14)

Her serene influence over the practical physiology classes has been our inspiration for the last five years. We have always found her so incredibly cool and capable in the midst of rabbits and frogs… Most of us will remember her too for those wildly successful pharmacology demonstrations, which entailed an enormous amount of preparation and were so often met with riotous delight.

Nutrition was not a focus in medical school education. In her role as lecturer, Muriel was able to advise senior medical students on thesis topics and tried to incorporate her special interest in nutrition into these topics. (2)

She also returned to her earlier fieldwork on ‘bush sickness’ in sheep with a particular focus on cobalt deficiency. In her spare time, she did research in areas of interest to her, which included investigations on the pharmacological aspects of hydatid disease and the toxicity of the karaka berry (used as a food by Māori but which could cause severe convulsions if not prepared correctly). (2)

Under the first Labour government, she became a foundation member in 1937 of the Medical Research Council (MRC) in the Department of Health and served on this committee for two decades. She was a member and later chair of its’ nutrition committee, which oversaw the Nutrition Research Department (NRD) (Muriel’s domain), which was based at the Otago Medical School and existed from 1938 to 1964. (2, 4) The purpose of the MRC was to advise the Minister of Health, Peter Fraser, on research funding. Fraser wanted research to concentrate on subjects of vital concern to New Zealand. Initially, these were identified as nutrition, hydatid disease, thyroid disease (goitre), and obstetrics, with nutrition receiving the most funding. (2, 14) Also in 1937, she was appointed to the Board of Health to represent the interests of women and children. At that time, the board’s focus was mainly on water and sewerage problems. She held this position until her retirement in 1964 and saw a significant broadening of the ‘scope of public health’ during this time. (2)

Second Marriage

Two years after the death of her first husband in 1940, Muriel found romance again. She met English-born Alfred Ernest Hefford, chief inspector of the NZ fisheries and director of fisheries research, at the Sawyers Bay research station near Dunedin. He fell in love with her at first sight, and they married on 20 June 1942. Like her first husband, Alfred was eighteen years her senior. He continued to work and live in Wellington until his retirement three years later when he moved to her home in the suburb of St Clair in Dunedin. Like Jim, he became the cook and managed the home. He had seven children from his first wife, who had died in 1940. His youngest son Jim who went to boarding school, was twelve years of age at the time of their marriage and had fond memories of biking around Dunedin and amusing himself at the medical school during school holidays. Muriel was never close to his other children, who were adults at the time of their marriage. (2) He died on 17 June 1957. (15)

Alfred’s conservative opinions may have been at odds with Muriel’s more liberal views. In a letter to his daughter in the 1950s, he wrote: (2)

I’m inclined to think that marriages were not only more stable, but on the whole, happier in the bad old times when wives did not dream of questioning the accepted fact that they were the subordinate partner.

His description of her domestic mannerisms offers some insight into life in their home. (2)

Muriel is a marvel. She has no trace of what might be called the aura of wifeliness, but she does excel in all the material ministrations of a home-maker, pampering me unnecessarily and rarely letting up for a few minutes from the various jobs about the house, over-working every part of her except her tongue and consistently putting in over-time at the Med. School. The drawback to it all is that she never has time to do things tidily and to leave things tidy. I don’t think she ever possessed that habit.

His health deteriorated during the 1950s, and Muriel dutifully cared for him. A childhood friend of Muriel’s recalled: (2)

When her first husband died, she felt unable to live alone, and shortly afterwards she married a very different man of a “higher class”. It turned out to be a most unhappy alliance, and just when it was near to breaking point, he died.

State Nutritionist World War II Years and Beyond

Brown suggests Muriel’s approach to her work was probably influenced by the philosophy of welfare feminism which did not focus on gender equality but ‘how the state could influence the well-being of women by improving conditions in the home, the chief site of women’s labour’. (2)

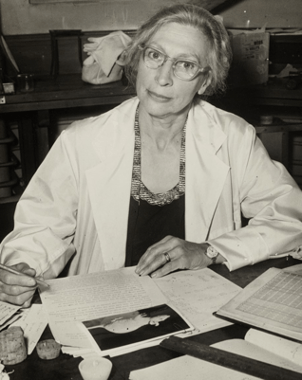

In 1940, Muriel entered the main focus of her life as she was appointed the first state nutritionist to the NZ Department of Health and retained that position until her retirement in 1964. She continued to be based at the NRD, University of Otago. During these years, she consistently worked on educating the public about nutrition. (2)

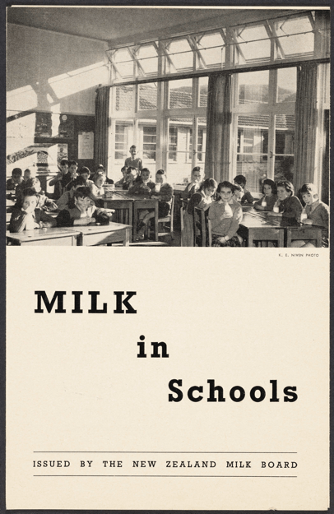

(Hocken Collections, Otago University Library MS-1078-111-001)By 1939, detailed dietary surveys of basic wage earners had been taken in the tramway and boot and shoe industries of Auckland, Wellington, and Christchurch as well as surveys into Māori diets. (4) Findings from the surveys indicated there was a low intake of calcium due to low consumption of milk and cheese. High-fat butter and cream dairy products were preferred. Programs were implemented to make milk and cheese affordable and a regular part of the NZ diet. (2) The school milk scheme, which offered every NZ child 300ml of milk a day, grew out of these findings and ran from 1937 to 1967.

Jane Wordsworth described it as an example of a fine scheme but not well implemented as it was time-consuming with practical difficulties of operation, which she described in her book: (17)

In general, it must be assessed as an excellent innovation, especially for children whose diet lacked essentials (many a child who never goes hungry is nevertheless malnourished). But it has to be recorded that many teachers, no matter what their opinions of its merits or otherwise, sighed with relief when milk-in-schools was abolished. Five minutes were usually allowed before morning interval as “milk time”. In the primer rooms, someone had to remember to spread newspaper in readiness for the arrival of the crates of bottles, to save the floor from milky drips and splashes. Also, in readiness there had to be a box of straws; monitors must puncture the tops and insert a straw in each. Two receptables were on hand for tops and straws separately. All milk not consumed had to be flushed down drains, with resultant blockages and smells. In hot weather, even pasteurized milk could go off before it was removed from milk-stand to classroom, and when winter came, full bottles were sometimes ranged around the stove or fireplace, with the same result.

In 1944, Muriel, at the request of the minister of health, became a member of the Central Milk Council, a position she held for the next thirty years; in addition, she chaired the Technical Subcommittee on Standards for Quality of Milk and had some positive influences. (2) She believed drinking milk was ‘our best single food’ and advocated it as part of a balanced diet for both children and adults. (4)

- She believed quality was the most important factor in changing attitudes toward and increasing milk consumption. This included having better hygiene on the farm and in the processing phase. (2)

- Tuberculosis was a problem in some dairy herds, so pasteurisation of milk was important. Schoolteachers blamed pasteurisation for the poor taste of milk, but the subcommittee recommended the protection of milk from light would improve the taste as light damaged the vitamin content of milk, which led to the oxidation of fatty acids and a rancid taste developing. Both schools and home delivery of milk improved from changes in this area. (2)

- She experimented with culturing yoghurt and homogenised milk. (4)

- She worked with the Plunket Society in updating the feeding tables for bottle-fed babies to increase protein and reduce fat content. She also devised new mixtures for babies with milk allergies. (4)

- She promoted the sales of skim milk powder and advised the Council of Organisations for Relief Services Overseas (Corso) against spending money on vitamin capsules for distribution in underdeveloped countries and instead recommended providing powdered skim milk for infant feeding. This helped in later years to increase exports to Asia and India. (2)

Through her work as the state nutritionist, Muriel Bell became a household name. Muriel’s research into vitamins and their content in NZ fruit, vegetables, cereal, and fish was communicated into a language that the general public could understand. She wrote public health pamphlets with names such as The Family Food, Children’s Meals, The School Lunch, Don’t Waste your Vegetables, and The Meat Ration is Adequate for Good Health. In 1948, she wrote a comprehensive book for nurses called Normal Nutrition, which the World Health Organization started to recommend to dental and medical students. (2)

Muriel organised local production of fish-liver oil during the war, which was necessary to supply Vitamin D and known to be essential for the prevention of rickets. Some schools administered a dessert spoonful of cod oil, but because of the rank fishy flavour, the practise was not popular. Some teachers insisted on the student saying “Thank-you” to make sure it had been swallowed and not spit out. (17)

Another NRD wartime effort was to improve the nutritional value of bread and flour by fortifying flour with Vitamin B-1. However, this was costly, and a less expensive means to retain nutrients was to alter the process of refining white flour to maintain more of the wheat grain. It was during this time period that wholemeal bread and whole-grain cereals were improved and introduced to the NZ population. (2)

Today, mothers in New Zealand are told that if exclusively breastfed, their infant will receive all the nutrients required. However, in the 1930s, mothers were told that even breast-fed babies did not get sufficient vitamin C and orange juice was given to infants. Due to shortages of citrus fruits during the war years, particularly after the bombing of Pearl Harbour, Muriel advised that rose-hip syrup, which was much richer in vitamin C, could be given instead. She published a recipe for rose-hip syrup in the NZ Listener and advised mothers to give this to their babies and children. (4, 17)

Another area where she left her legacy was in the prevention of dental caries. She visited the United States in 1952 and became informed about their experiments with fluoridated water supplies. On her return, she campaigned for fluoridation and won battles locally for fluoride to be added to the drinking water. It was during this era that she gained the nickname ‘Battle-Axe Bell’. The mayor of Auckland, Dove-Myer Robinson, was one of her stronger opponents. In 1956 the government appointed a commission to investigate fluoridation; from 1958 she was a member of the Fluoridation Committee of the Department of Health, and by 1966 most communities had fluoridated water. (4)

Muriel also became involved in developing the diet used for the humans and the dogs on the 1956 – 1957 trans-Antarctic Expedition. A two-minute recording of Bell discussing her work for this expedition can be found at the following link: (18) https://teara.govt.nz/en/speech/116/bell-discussing-her-work-for-the-1956-57-trans-antarctic-expedition

Winding Down

As she neared retirement, she went on various trips, partly to look for her successor. In 1960, she spent 4 months away, which included attendance at the International Conference on Nutrition in Washington, D.C. Muriel did not align herself with some of the dietary theories coming out of the USA on heart disease. She was convinced that being overweight and inactive were the main factors contributing to heart disease and believed genetics might also play a role.

The field of nutrition was failing to attract bright young researchers, and the NRU was insisting the successor should have several years of training. In addition, Muriel was insisting she must do the training of her successor. A further impediment to finding a suitable successor was that NZ research facilities and funding were not competitive with the USA and Europe. She did not help her cause by her physical appearance. An old friend described this aspect of her: (2)

Her frugality was phenomenal, and I well remember being taken with her one evening to visit a colleague of hers in their charming home in Napier. Muriel sat there, happy and relaxed, dressed for a visit. She was wearing a dress she had made for herself, hem uneven and frock unattractive. She was wearing a pair of her late husband’s socks and a pair of many-times washed and almost worn-out tennis shoes. An incredible appearance, but what struck me, and this is why I am recording it, was the deep respect and might I say love that her hostess and host clearly showed they had for her. She was in every way a remarkable woman.

In 1963, the dean of the medical school, Charles Burns, was advised that Muriel’s beloved NRU was unlikely to get further funding from the MRC. Muriel was sixty-five in 1963 and would be due for retirement. The secretary of the British Medical Research Council, Sir Harold Himsworth, was asked by the NZ MRC to make recommendations on the fate of the NRU. He acknowledged finding ‘research of real quality in progress’, but he was not prepared for the ‘high quality of research in a considerable proportion of places outside the Otago Medical School’. He suggested a new structure of medical research be adopted with six scientific subjects (internal medicine, surgery, pathology, microbiology, physiology and biochemistry). He believed the classical era of nutrition was over and should come under the jurisdiction of biochemistry. (2) A decision was made by the NZ MRC to abandon its funding of the NRU – isolated projects were funded until the end of 1968.

Many fellow scientists, especially those on the NRC, expressed their protest at the way the government had acted and called it a ‘retrograde step’ for nutrition research in NZ.

Charles Burns recounts his last personal encounter with Muriel shortly after the announcement (which had been made when she was overseas) of the disbanding of the NRU: (2)

She was a broken woman, and no words of mine were of any help, nor I would believe of consolation – because there was in fact nothing that at that point in time we could do about the situation. From that time onwards it seemed impossible to get close to her and even the decision to establish a Nutrition Research Society for New Zealand, which we thought would be received by her with joy, brought little or no response: her sense of justice had been so disturbed that it appeared as though she just wanted to be left alone with her thoughts, and her day to day tidying up of her Department.

Honours and Memberships

Muriel was made a fellow of the NZ Institute of Chemistry in 1941, the Royal Society of New Zealand in 1952 and the Royal Australasian College of Physicians in 1959. (4) That same year, she was appointed Commander of the Order of the British Empire in recognition of her lifetime of service to the field of public nutrition and public education on health. (2)

She was also a member of the Physiological Society of New Zealand, the Nutrition Society of New Zealand, the New Zealand Dietetic Association, and the New Zealand Dental Association. She co-operated with an influential network of professional women, especially Dr Elizabeth Gregory (head of School of Home Science) and Dr Helen Deem (medical advisor to the Plunkett Society), and executives of the New Zealand Medical Women’s Association and the New Zealand Federation of University Women. She was not supported by the medical establishment, who were largely ignorant about nutrition. (4)

Muriel received many accolades at the time of her enforced retirement, but the highlight came in 1968 when she was awarded an honorary doctorate from the University of Otago; the citation described her as ‘a peerless and tireless lady.… who campaigned with unexampled energy to make the findings of research available for the common benefit – from rose hip syrup to fish liver oil, from the extraction rate of flour from wheat to the iodisation of salt, from milk in schools, to fluoride in the water supplies’. Her colleagues noted that, for once, she chose to dress up and bought a new blue suit for the occasion. (2, 4)

A Sad Ending to an Illustrious Career

Muriel never recovered from what she had spent a lifetime creating in the NRU. Following her second husband’s death in 1957, she lived alone at her St Clair home. Her two sisters, Elsie and Chris, died in 1972, and on the advice of family and friends, she moved into a flat. In addition to her orchard and garden, with this move, she lost her home of more than thirty years. She never settled, and, on her death, most of her belongings were still in boxes.

On 2 May 1974, at the age of seventy-six, Muriel was discovered dead in her home. Her step-sister Jean had been unable to contact her for several days, and the police had to break in. She had no pre-existing conditions that could be identified as a cause of death as she had always treated herself, so an inquest was required. She had choked on her own vomit, and the verdict was gastroenteritis. On her typewriter was a finished article on the toxicity of the karaka berry, a project she had started to research in the 1930s; it was published posthumously. (2, 19)

Muriel had left instructions that there was to be no funeral service, so she was cremated on 4 May 1974, and the ashes were then sent to Dunedin cemetery. Her stepsister Jean, against Muriel’s wishes, organized a memorial service for friends and family. Colleagues spoke of her unparalleled devotion and said simply, ‘There will never be another’. (2)

In her short biography for the Dictionary of New Zealand, Mein Smith summarized Muriel Bell in this charming way: (4)

Kind, warm and caring, Bell had ‘infinite patience’ with people and was supportive to her staff. Always innovative, she entertained her students with her ingenuity and sense of fun. Unusual, at times bizarre in her behaviour, she startled visitors, for example, by offering them a cup of tea while she was testing rats. If the kitchen bench was full, she would work on the floor. She wore plastic sandals because she had hammer toes, and amused and perplexed friends with her unreliable cars.

Muriel Bell’s legacy lives on through the University of Otago Department of Human Nutrition Muriel Bell Prize for a post-graduate 400-level student who is judged to have achieved the highest standard of attainment in Human Nutrition, (20) the Muriel Bell Lecture, a free public lecture held yearly at the Scientific Meeting of the Nutrition Society in New Zealand. (21) In addition, her friend and medical school classmate Frances Preston gifted a sundial in the rose garden at Wakari Hospital, Dunedin. (2)

Bibliography

1. Muriel Emma Bell, photographed on 30 July 1952. Wellington: Alexander Turnbull Library; 1952 [22.02.2023]. Available from: https://teara.govt.nz/en/photograph/2748/muriel-emma-bell-photographed-on-30-july-1952

2. Brown D. The Unconventional Career of Muriel Bell. Dunedin: Otago University Press; 2018.

3. Births, Deaths and Marriages Online Wellington: New Zealand Government Internal Affairs; [26.01.2023]. Available from: https://www.bdmhistoricalrecords.dia.govt.nz/

4. Mein Smith P. Bell, Muriel Emma Wellington: Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand; 1998 [updated 01.06.201225.01.2023]. Available from: https://teara.govt.nz/en/biographies/4b21/bell-muriel-emma

5. Maxwell MD. Women Doctors in New Zealand: An Historical Perspective 1921-1986 Auckland: IMS (NZ) Ltd; 1990.

6. Imprisoned conscientious objectors, 1916-1920 Wellington: Ministry for Culture and Heritage; [updated 01.08.2016]. Available from: https://nzhistory.govt.nz/war/the-military-objectors-list

7. Bell ME. Mineral deficiencies in New Zealand. Influence on human and animal health. J Am Diet Assoc. 1962;40:204-7.

8. Bell ME. The blood-sugar level in vitamin B(1) deficiency. . Biochemical Journal. 1931;25(5):1755-68.

9. Bell ME, Gregory E, Drummond JC. Studies of the alleged toxic action of cod liver oil and concentrates of vitamin A. Zeitschrift fur Vitaminforschung. 1933;2:161-82.

10. Bell ME. Albuminuria in the normal male rat. . J Physiol. 1933;79(2):191-3.

11. Bell ME. High protein diets and acid-base mechanism. . J Physiol. 1933;27(5):1430-7.

12. Bell ME. Cystine and nephrotoxicity. Biochem J. 1933;27(4):1267-70.

13. Drummond JC, Bell ME, Palmer ET. Observations on the absorption of carotene and vitamin A. Br Med J. 1935;15(1):1208-10.

14. Page D. Anatomy of a Medical School: A History of Medicine at the University of Otago 1875-2000. Dunedin: Otago University Press; 2008.

15. Alfred Ernest Hefford: Geni; [05.07.2023]. Available from: https://www.geni.com/people/Alfred-Hefford/6000000023253791032

16. Dobree JP. Primary school boys drinking their school milk, Linwood, Christchurch Wellington: Alexander Turnbull Library; 1940s [22.02.2023]. Available from: https://tiaki.natlib.govt.nz/#details=ecatalogue.263980

17. Wordsworth J. Leading Ladies. Wellington: A.H. & A.W. Reed; 1979.

18. Bell discussing her work for the 1956–57 trans-Antarctic Expedition Wellington: Dictionary of New Zealand Biography; 1964 [11.07.2023]. Available from: https://teara.govt.nz/en/speech/116/bell-discussing-her-work-for-the-1956-57-trans-antarctic-expedition

19. Bell ME. Toxicology of karaka kernel, karakin, and beta-nitropropionic acid. New Zealand Journal of Science. 1974;17:327-34.

20. University of Otago Department of Human Nutrition Scholarships and Prizes Dunedin [18.07.2023]. Available from: https://www.otago.ac.nz/humannutrition/study/scholarships-prizes/index.html

21. Conference 2023 – Nutrition Society of New Zealand and Nutrition Society Australia 2023 [18.07.2023]. Available from: https://www.nutritionsociety.ac.nz/newsandevents/society-meeting-2023